"I'm afraid I can't accept less than the sum I have named", said Harper G. Best firmly, bracing his hands against the edge of the desk. "In fact, I'd rather not sell at all if you are not prepared to meet my figure." "I'm afraid I can't accept less than the sum I have named", said Harper G. Best firmly, bracing his hands against the edge of the desk. "In fact, I'd rather not sell at all if you are not prepared to meet my figure."

He looked calmly at the four men facing him. They were queer little chaps, those Venerians, with their small, slight figures, leathery skins which it was their fancy to dye in brilliant hues to purple, green, or red, and balloon-like skulls so thin and delicate that they had to be protected by close-fitting steel caps. Their little sulky-child faces did not reveal much of the keen penetrating intelligence which had made them famous throughout the

known planets.

"We are willing to make a reasonable offer. But you must remember", said the Venerian spokesman, "that we bear all the expense and trouble of transport. You must take that into account."

He was the only one of the four who could speak English, since it was extraordinarily difficult for the Venerians with their double tongues to pick up Earth languages, but he was transmitting his speech, and Best's replies, by mental radio to his three companions.

"I have allowed for that", replied Best: "But I myself will have many liabilities to meet. The least I can accept is the equivalent of 500 billion dollars."

The Venerian signified swift assent, and Best leaned back in his chair with well-hidden relief.

"Very well, gentlemen", he said. "I think you'll find you've made a good deal. I've put a lot of time and energy into this moon of ours; although, of course, that won't increase its value for you, since I understand you intend to turn it into a sort of pleasure-city. I need the money; that's why I'm letting it go."

The Venerians sat still, their little faces revealing no change of expression. They might, or might not, have been interested in Best's speech, but they showed not the slightest sign either way.

"I was the pioneer, you know", Best continued reminiscently. "My ship, the 'Harper G. Best', designed and built by my craftsmen, manned by my crew, was the first vessel to land on the moon, while others were still struggling to get beyond the earth's atmosphere. They planted my flag there, and established my claim. That was thirty years ago".

Pausing for effect, he glanced at the little men with narrowed blue eyes. They returned his look without expression..

"We had a terrible struggle at first", Best went on. "The moon was airless and waterless. Then we got our first city built in the crater of Tycho, and began to work some of the more accessible mines. Regular space-ship runs had to be established, for every scrap of food, water and air had to be brought from earth. Soon we set up a re-fuelling base and that made possible trips to Mars. Yes, we had a fight, but I've made plenty out of it, I may admit. Contracts for mining, rent for space-ship grounds, factories, all the various needs and activities of the new colony centred in me. And we haven't explored it all yet. Still, as I say, I've other interests in mind and 500 billion dollars will be more good to me at the moment."

The little Venerian inclined his head.

"Then the deal is concluded, Mr Best", he said. "The equivalent of 500 billion dollars will be placed to your credit in the Venerian banks, to be withdrawn on demand if required. Meanwhile, we will go ahead with our arrangements for transporting the moon."

They rose. In a few minutes they were filing out between two rows of attendants to a fast car which was waiting at a side door of Best's vast office buildings. The reporters who rushed forward had no chance to ask questions, for the attendants were seven-foot steel robots with electrified arms for driving back unwelcome hustlers.

Despite this, information must have leaked out somehow, for the evening editions bore full-page banners: "500 Billion Dollar Deal Through"; "Moon Sale Concluded"; "Best Sells the Moon to Venus."

@@@@@@@@@@

A copy of the "New York Senate" was awaiting James Barlick, assistant at Dill Observatory, Arizona, when he climbed up from the sun-room in the bowels of the earth after a hard day's work on solar spectra. He rushed with it into the transit room, where his chief was chatting with a mechanic.

"It's true, Dr Vlatch!" he shouted. "I wouldn't have thought it possible. He's actually put the deal through - sold the Moon - our Moon - to Venus! I thought the whole thing was a hoax, but here it is." He ran his eyes down the columns of print and read out: "Mr Best refused to make any statement, but it is thought that the price accepted is equivalent to 500 billion dollars. 'It is understood that the transfer of the moon is to be undertaken by the Venus Development Commission, which is solely responsible for its accomplishment. Mr' . . . something I can't pronounce 'and three other representatives of the Commission left for Venus at 4 o'clock this afternoon. They made no statement.'"

"It's preposterous - absolutely preposterous!" exclaimed Dr Vlatch. "He can't do it. No power on earth would recognise it. He can't sell something that doesn't belong to him."

"But who does the moon belong to?" pondered Barlick. "It's a question we've never thought out before, isn't it? You can't say it belongs to this or that country. Before Best stepped in it belonged to everybody - or nobody. I suppose in a way we've been acknowledging his ownership all these years without realising what

it might involve."

"The whole thing's a piece of utter nonsense", said Vlatch, firmly determined to believe that it really was so. "Simply a piece of publicity. It will fall through, you'll see. Best's a lunatic."

The mechanic went out and stared up at the slip of moon just setting in the sunset glow. He scratched his head. It was a queer business.

Barlick remained staring gloomily at the crumpled "Senate", and after a minute Vlatch laid a sympathetic hand on his arm.

"It would be bad for you if this turned out to be true it, Barlick?" he said.

Barlick nodded. "And not only for me", he said.

They were silent for a moment.

"That fool doesn't realise - or doesn't care!" broke out Barlick savagely. "Take away the moon - and what happens? The lunar tides stop. Every tidal power station in the world stops. The solar tides alone can never keep them going. Just as we've begun to learn the secret, to win from the tides power sufficient to raise our standard of life a little more, this happens. Think what it will mean!"

"I'm thinking of your invention, Barlick", said Vlatch. "You had just persuaded them to try it out; but now it simply won't have a chance."

"I suppose not", muttered Barlick. "And yet if I could have got my gadget across, it would have increased the efficiency of the tidal stations tenfold. But with only the solar tides to depend on it won't have a hope. The companies will simply close down as soon as the lunar tides ceases. We've come to rely so much on tidal power now that it will almost .bring civilization to a standstill. This sale is folly of the maddest kind!"

"It may seem little beside the general calamity", said Vlatch, "but to me too, the departure of the moon will be a heavy loss. I've spent almost forty years of my life studying its surface, and now it's going to be taken so far away that my future observations will be practically valueless."

Barlick stamped down the room.

"The man's mad - criminal!" he cried .furiously. Then all at once he marched to the door.

"I'm going to New York, Vlatch!" he said abruptly. 'I'm going to see this madman and bring him to his senses. I'll kill Best before I'll see him deal humanity a blow like this!"

@@@@@@@@@@

So occupied was James Barlick with his own seething thoughts that he did not stop to consider whether others, reading the same news, might not have the same impulse as himself. When he reached New York, however, he found it swarming with deputations of protest. Best had been swamped with requests for interviews, and had retaliated by assigning to all, the same hour of the same day. At the appointed time therefore Barlick found himself wedged in the entrance hall of Best's New York office amid a furious, eloquent, sweating crowd.

There representatives of shipping companies religious bodies, port authorities, foreign governments, mining and minerals trusts, and municipal councils. Delegates from the International Astronomical Union compared. grievances with committees from the Society for the Preservation of Rural England. Ship-building firms from tidal river cities send their men to mingle with the directors of the Earth-Moon-Mars Spaceship line. Angry comrades from the Seamen's Union and the Union of Interplanetary Workers fought for a hearing. Private astronomers from all continents left their instruments and flocked to the best building in New York. Barlick saw from the first that it was hopeless: Best evidently had no intention of appearing.

Harper G. Best was at this time reclining on an air-bed in the garden of his summer house at South Palm Beach, Florida. At the hour of the mass appointment, he switched on the tiny, neat transmitting set which fitted into the pocket of his tunic and spoke into it with quiet finality. His amplified voice blared from several loud-speakers in the Best office.

"Gentlemen'', he said, "I'm sorry, to disappoint you, but it happens I've been called away on business. I know what you're all going to say, but it doesn't change my mind. The moon is, mine by right of conquest - contest that if you can. Haven't you acknowledged it by coming to me for contracts to get out lunar ores, and to build space-stations? And now I've had a good offer from Venus, and I've closed with it. Venus hasn't got a moon, and she wants one. We've got a moon - or rather I have - and I've got my fair price. The bargain goes that the Venus Development Commission devises its own method of getting the moon from here to Venus. That's out of my hands; they can do as they like. Legally, my position is perfectly sound. Nobody owned the moon before I took over; nobody can protest, if I sell it. So I'll bid you good-afternoon, gentlemen."

There was a momentary hush over the assembled throng in the Best building, and then a confused buzz of shouts and; exclamations broke out. "We're ruined!" was the cry of everyone who had to do with seas or rivers. With no high tides to bear ships up to the towns, the river-ports saw themselves deserted. The immense tidal power stations, which had sprung up all over the world in the past fifty years, were facing complete stoppage. Almost every trade or business which used electrically-run plant was up against it, for the dependence of the earth on tidal power had been increasing steadily ever since methods of tapping that great source had been developed.

The firms which had been making millions out of the lunar ores would close down; the interplanetary companies which drew their revenue from the transport of ores and a small tourist trade were forced into ruin also for the moon was their refuelling base and although Venus-built vessels travelled between the earth and Venus, earthmen had so far failed to construct ships capable of reaching Mars in a non-stop run. The departure of the moon would mean to millions of men and women, the loss of work and livelihood. It was a stricken, terrified, enraged crowd that milled about Barlick in the Best offices.

"If this happens", said a voice in Barlick's ear, "it will cause a plunge back into the dark times of the twentieth. century."

Barlick turned and saw that the words had come from a man who was wedged against his shoulder. The man was wearing a long dark gray cloak with a hood which completely hid his face, a dress often adopted by Martians to protect their delicate skins from the comparatively brighter sun of earth. His voice, however, had not the Martian ring. Barlick responded with a nod.

"There must be some way of stopping it!" he replied. "Heavens, I can't think in this crush!"

He used his shoulders vigorously and soon managed to reach the street. As he turned to go towards his hotel he found that the grey-cloaked man had followed him and was falling into step.

"Why do you suppose the Venerians want our moon?" asked the stranger in a conversational tone.

"There's no reason I can think of except sheer greed and vanity", replied Barlick viciously. "From what I know of the Venerians, they combine amazingly brilliant minds with astonishingly childish dispositions. They can't bear to think of anyone having something they don't possess; that much I know of them. The galling thing to me is that they won't make any practical use of it; it will simply be turned into a sort of pleasure resort for the idle Venerians."

"They say Europe is threatening war over this", went, on the man in grey. "And yet nothing will stop Best. His other interests are too pressing; he needs the money urgently."

"You speak as if you knew his reason for selling out like this", said Barlick, with a glance of suddenly aroused interest at the dark stranger. Certainly he was too short for a Martian and his speech was too perfect. Yet surely only the most eccentric of earthmen would adopt the distinctive Martian garb, for the men of Mars were nowadays despised on the other planets.

"I know", replied the other. "And I must let others know as well. But I can scarcely think how to begin. It is a strange story. May I tell you?"

If you wish", said Barlick. Sensing that the stranger would speak no further until they were alone, he walked on in silence until they reached the hotel.

"Excuse me if I don't remove this hood", said the man in grey, when they had entered Barlick's room. "By the way, my name is Jessel." He paused, and then added, "My father worked in the mines of Mercury".

"You are a native of Earth?" Barlick asked, after he had introduced himself.

"I am", replied Jessel. "You do not see the significance of my last remark. Unfortunately there are many in the world for whom it would have the most tragic meaning."

Barlick gazed at him in surprise, but the painful and embarrassed tones of Jessel's voice made him restrain his curiosity. After a pause Jessel spoke again.

"Best is also interested in Mercury", he said. "Do you know what comes from the mines of the inmost planet?"

"I don't know much of Mercury at all", confessed Barlick. "I've never visited any of the other planets. But of course not many people go to Mercury, except to work."

" That's true", said Jessel. "But just about the time of the first landing on the moon there was discovered in the Mercurial mines a strange new substance whose properties are only beginning to be explored.. It has always been referred to simply as X. Recently an explosively radio-active substance, X2, has been extracted from it, a substance which is rapidly proving to be the perfect rocket-fuel."

"And Best, you say, is interested in this?" Barlick asked eagerly.

"I think I am right in concluding that his reason for selling the moon is simply to raise the credit for the purchase of these mines," said Jessel impressively. "As you know, Mercury has been a colony of Mars ever since the Martians conquered it during the last great days of their world-unity, since vanished. Nobody has suspected the possibilities. The debased remnants of the Martian race don't realise what it is they are handing over; they are too busy with their petty political wars. Best has kept it well hushed up."

"The perfect rocket–fuel?" pondered Barlick. "Then that means he can supersede our present rather clumsy methods - perhaps even do without refuelling bases?"

"With X2 as fuel it would be possible to make direct flights to Jupiter or even Saturn", said Jessel. "If Best has this stuff under his control, he can run ships over the known, and unknown parts of the system. He can crush out all comers. He'll be the boss of the Solar System!"

"But there must be others who know this too", cried Barlick. "Why has no word of it leaked out?"

"I doubt if there are many", Jessel said. "The miners are simple folk, unaware of high interplanetary affairs. My father was a humble man, but I have had the benefit of a Venerian education, since I was sold into the slave-markets there before - before any of the marks appeared on me. With me they were unusually late in coming.

"I don't understand", faltered Barlick, trying to fill in the awkward pause which followed.

"A lot of children show the marks when they are born", Jessel said quietly, musingly, almost as if fancying himself alone. "Such children are destroyed right away. With others it does not show until the age of eight or nine. They are taken away then, and the parents are simply told that they have died of some internal trouble. But I was sixteen before the first signs came. It's the effect of the mines, you see; the radiations from X and X2. It doesn't affect the miners themselves very much but it comes out in the children - sometimes. They never know whether it will or not; it's unpredictable. With me, they thought it hadn't."

The folds of the grey cloak stirred and he slid out a wrapped hand, limply distorted, curiously misshapen, and seeming as if only its tight, brown bandages held it together. He raised it slowly to the grey hood grasped the edge, and paused. Then he let the hand drop.

"I had better not show you my face", he said in a quiet tone, which was tragic in its very restraint.

For a moment, Barlick could not speak.

"Best intends to develop the Mercurial mines", continued Jessel presently, in a calm, steady voice. "This will mean thousands of additional workers, all to be exposed to the ghastly influence of X2 radiations. Workers in the rocket ships may not be so strongly affected, but there is no certainty. As for passengers, they should not run much risk, and I believe there are safeguards, but these cannot be used to protect men who must: work with the stuff. You can see from this the price which humanity must pay for what Best would call progress."

He sank into a chair.

"I am not very strong now," he apologised. "Sometimes it is a weariness to drag my body about. Yet I cling to life, as we all do who escape; until the last agony comes."

"But surely Best doesn't know all this?" Barlick cried. "The Martians may have kept it secret .from him; after all, they are different, but we of earth have some ideas of honour and decency. Best would never expose his fellow men to this if he knew."

"Best knows, nevertheless", said Jessel, without a shade of doubt in his tone. "I came here to the city, I who have never ventured near to another human being since I first knew the signs were on me, to show Best this face that I dare not show you, and beg him to think what his action will mean. It was useless; I couldn't get near him. But I have found out that he knows; and that despite this the first cargo of X2will reach Earth within a month. Then the experiments will begin. Soon space-ships will traverse the entire solar system. A step forward - another mile-stone of progress passed! So the men of earth will say - until they begin to discover the cost."

Exhausted by his emotion he almost collapsed in the chair. Barlick approached him anxiously, and then all at once became aware of a sickening, foetid, charnel smell, the stench of festering, rotting flesh. Jessel's body must be a living sepulchre, a walking grave. What hideous thing was Best calling down upon the human race?

@@@@@@@@@@

"But what are we to do, Vlatch? cried Barlick restlessly. He was feverishly pacing the library at Dill, his mind a turmoil of fear and doubt and rage.

"Are you sure you're not taking all this too seriously?" asked Vlatch. Barlick's story had affected him strangely, but in the absence of Jessel it could riot completely convince him. It seemed impossible that so wild a story could be true.

"This man may be crazy", he went on. "Events like this usually bring forth a crop of insane tales and pretensions from madmen and semi-lunatics. It sounds incredible. And yet—Mercury is a queer planet. The story certainly hangs together. But the devil of such yarns is that they are always plausible."

Unable to decide, he fell silent. But there could be no doubt in Barlick's mind.

"I believe it, Dr Vlatch," he said "I'm firmly convinced of its truth. There was sincerity in every tone of the man's voice—no trace of hysteria or mental strain. I know he did not deceive me. I admit I would scarcely allow myself to believe that Best could be such a devil, but his very act is selling the moon proves that he has absolutely no thought for the mass of humanity. Why should one man have so much power? After the wars of the 20th century, man swore that never again would it be possible. How has it come about again?"

"If you really believe this story, then, Barlick, you must act", advised Vlatch. ""We must make this known to all the world."

"He is strong enough to defy us all," muttered Barlick. "We must get at him personally. Or we must find out where his is going to store the stuff and devise some way of destroying it or ruining his experiments.—Oh, that sounds crazy!" he added despairingly. "There seems no way out."

Vlatch shook his head hopelessly, and Barlick stared blindly at a row of bound astronomical journals.

"Have you seen the camp yet?" Vlatch asked presently, hoping to rouse is assistant's interest. "Did you know they'd set up on Mount Chester?"

"Camp? Who? What do you mean?" asked Barlick impatiently.

"The men from Venus - little devils," said Vlatch. "They seem to be intending to erect their apparatus there. We might stroll over presently and see what they're up to, if you like."

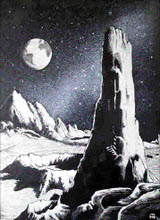

The low sun's fading gilt lent an other-worldly hue to the hill on which strange buildings had sprung up during the few days of Barlick's absence. The two astronomers walked. slowly through the dusk in the direction of Mount Chester. Against the white structures on the hill there passed and repassed tiny distant coloured figures, the queer little men of Venus busy on their extraordinary, unbelievable task. Here they were, come to Earth to steal away its ages-old partner, the moon which had accompanied it so faithfully on its Journey round the sun for millions of eons. Earth and Moon - now Venus and Moon. Incredible thought! In the quiet dimness of evening it was scarcely to be seriously entertained.

Within months there had begun to rise on the summit of Mount Chester an enormous and curious mount which bristled with strange instruments and protuberances. The Venerians went busily about their work and during that time, the men at the obserrvatory saw nothing of the little coloured people. Barlick was half crazily racking his brains for some way of getting near Best; Vlatch, a worshipper of the moon from his boyhood, was quietly making his last set of observations onthe globe so soon to be taken beyond the limit at which he could note its finer details. The bitterness of his feelings was shown by an absolute refusal to discuss the question. At the end of a few weeks, however, Barlick's curiosity as to the means they meant to employ for the transfer of the moon overcame his resentment, and he began to seek out the Venerians.

Mistrustful of all earthmen, they were reserved and shy, but an invitation to inspect the observatory delighted them, and on the appointed evening they sent down a delegation of half a dozen. Vlatch refused to appear.

Fortunately for Barlick, two of the Venerians spoke English, which they had learnt at an American university and although their double tongues rendered their speech obscure at times he did not find it too hard to talk to them. They were not at all reticent about the methods they intended to use on the moon. If anything, their surprise at the need for an explanation was made too apparent.

"We shall accomplish our end in something the same way as the earth has been using for thousands of years to drive the moon away", explained one, whose name Barlick could never pick up but whom he identified by means of his elegant, emerald-green skin. "I refer to the acceleration of the moon in its orbit."

"But I can't see how you are going to manage that", said Barlick. "As we on earth would explain it, the tidal protuberance raised on earth by the moon has its reciprocal effect on the moon by accelerating its orbital motion, so that it is forced into a wider orbit. That is what you're referring to, isn't it?"

"Yes, you are right," replied the Venerian in his slurred voice. "So you can see the simple solution. We project what we call a Rho-ray - a narrow beam - into space, so that it is focussed just ahead of the moon. The ray acts intermittently; every time it is switched on it gives the moon a jerk and accelerates its motion. You see? It pulls the moon onwards in its path, thus increasing its speed and widening its orbit. The moon will begin to spiral out from the earth until it reached a point where it will be completely under the power of the sun and free from the earth. At this point we let it fall into an orbit round the Sun from which, at favourable intervals, we hope to divert it gradually by using the same force for the opposite purpose of slowing it down. By this means, we shall narrow the moon's orbit round the Sun until it comes near Venus, when we shall capture it and manoeuvre it into a suitable orbit round our planet."

"It sounds as if it may be a long job," said Barlick, appalled at this calm juggling with a two-thousand mile globe, even although the proceedings were as yet theoretical.

"We expect to free the moon from the earth in about a month," replied the Venerian. "But the other part will be longer, since we shall have to wait for suitable opportunities to sue the Rho-ray. It will take anything from five to eight years."

"You haven't started yet, then?" Barlick asked.

"We're still assembling the apparatus", answered the green Venerian. "And all the time our technicians are busy with that side, the mathematicians are calculating the exact positions of the moon in the heavens, and the changes to be effected by the pull of the ray. As you will know, the exact position of the moon is extraordinarily difficult to calculate, and minute accuracy is absolutely essential to us, for should the narrow beam ever be slightly misdirected, its effect will be nullified. Among other things we are working out the precise period of the Earth's rotation and the correct position of the axis of rotation, which is very variable. Should we make a mistake with either of these components our labour might be in vain."

"You will have a difficult task", commented Barlick. "Our astronomers on earth have not yet finished it down to the last detail."

Immediately the words had crossed his lips he sensed the slightly amused contempt with which the Venerian met it, and the subtly expressed consciousness of intellectual superiority made him seethe inwardly with embarrassment and fury.

"I'd like to see you make a mess of things!" he fumed silently.

@@@@@@@@@@

"Atomic power, probably", Barlick said to Dr Vlatch one night a few weeks later as they stood together at the door of the main dome looking towards Mount Clever. "They'd need it for all the power they'll want. They've got at the secret we have been seeking for years. but we'll never hear it if they can help it."

"I suppose so", said Vlatch, scarcely listening to the younger man's remarks. He was tired, for he had been working every available hour at the telescopes. There was so little time left now.

The apparatus on Mount Chester now towered high into the sky. Its strange projections and irregularities struck weirdly into the darkling sky. Suddenly Barlick felt a touch on his arm. A figure, seemingly half formed out of the evening dusk, stood just behind him. It was a man In a long, grey, hooded cloak.

"Jessel!" cried Barlick. Vlatch looked round curiously.

"I have walked a long way", said Jessel in a whisper. He was obviously faint.

"Come in!" ,invited, Barlick. "This is the man I told you of", he added to Vlatch. "Now you can speak to him yourself."

"I had to venture here - forgive me", began Jessel, when they were seated in Dr Vlatch's study. "I know I should not show myself among men. But I have made a discovery which may be of use to you. I know where Best proposes to dump his imports of X2."

"But how can you be sure?" asked Barlick. "How did you find out?"

"I know a great many odd people", said Jessel. Some of them are Martians, and they are good at finding out such things. One of them told me this, that Best is using a certain site for some purpose which is evidently very secret. I concluded that it could only be the X2 dump."

"And you think he is going to build experimental ships here?" Vlatch cut in.

"I've no idea, but it seems very likely", replied Jessel. "Perhaps if we wait, we may hear more. But meanwhile, I've prepared a rough sketch of the place."

The wrapped, distorted hand emerged from the grey cloak, laid a thick sheet of paper on the table, and withdrew quickly to hiding. Barlick caught the startled glance Vlatch flashed at that hand, and saw pity follow in his eyes."

"Amazon district", muttered Barlick, bending his head over the map. "Well, it's isolated enough. And yet if we want to do any good we must get at it and destroy it completely. That seems to be the only way we can make Best take notice."

"Why not warn him?" suggested Vlatch. "Let him know that we have found out where his dump is; that ought to scare him. Then we can threaten to destroy it if he won't cancel the sale."

"No, we must finish off the dump first, and then inform him that we'll do the same with every cargo he brings over, unless he gives in", Barlick said without looking up from the map. "We must find out how to explode the stuff. Jessel says its highly explosive."

"But how can you do that?" demanded Vlatch. "It's impossible; our only hope is to bluff him into thinking we can. We'll have to use what we do know to best advantage."

"Now we know - or hope we know - where the stuff is, it isn't impossible", returned Barlick, with quiet assurance. "The dump will be closely guarded, but we can get past that, for we can send into it something they will never have thought of. We can explode the whole dump by means of a long-distance radio-beam."

"You're crazy!" cried Vlatch. "The kind of beam you are thinking of is only a scientist's dream."

"You will need a very great amount of power for that", said Jessel. "The only source I know of, which would give enough, is the Venerian atomic machine, and I'm afraid we wouldn't be able to get hold of one."

"I don't need any atomic machine, " said Barlick. "This business concerns the whole earth, and everybody's got to co-operate. We'll get every tidal station in the world into this; they won't hang back when they know there's a chance to save themselves, for they know that if the moon goes, they go too. We'll draw power from all the stations, concentrate it in some convenient spot, and project into Best's dump, a beam that will scatter it in dust to the four winds. I'll bring them all in - America, Europe, China,. Africa . . ."

"Will you?" said Vlatch. "I'm afraid you won't get much co-operation from Europe - or China. Don't you know what's in the news these days, Barlick?"

There was a moment's profound silence. Barlick s eyes fastened unconsciously on the grey hooded figure beside him as Jessel's words came back to his mind. What was it he had said, that day in New York? "Europe is threatening war over this!" So it was true.

What the nations across the Atlantic chose to call the high-handed action of the American government in disposing of something which, they claimed, belonged to the whole world, had snapped the tension of irritation, envy, petty trade quarrels, which had been mounting between the two continents. And now they were ready to blaze into war. The American government was powerless in the matter of the moon sale; no legal talent could disprove Best's right of possession, acknowledged by the government itself, for no other claim could be put forward. Three continents were rushing to arms.

"I'm sorry, Barlick", said Vlatch, half in apology for the sharpness of his tone and half in sympathy for his assistant's despondent look. Barlick shrugged sullenly.

"Why are men such fools?" The cry, old as man himself, came bitterly from his lips. "Here's a time when common peril faces every man on earth, when everyone should unite to defeat Best's infamous sale - and they must go and start a war."

Perhaps it's because they've come up against a problem they can't solve, and can only justify themselves with an outburst of blind violence", said Vlatch philosophically. "That's been the cause of more than one war, in my view."

"Then there's no hope?" asked Jessel despairingly, turning his hooded head from one to the other.

"There is", said Barlick, "one hope." His face was pale, firmly set. "We have only the tidal stations of America to rely on", he continued. "Alone, as things are, they can never raise enough power for the tremendous force of the beam we must have. But there is a method of increasing the power so much that they will be able to do easily what the stations of the whole world could scarcely do. Vlatch . . ."

"Your invention?" cried the astronomer. "Can it be done?"

"If we can persuade, coax, force every station oh the American continent to install the new machinery I have designed. Surely they will be only too willing to do that rather than lose the source of their power altogether."

"But how will you convince them, Barlick?" asked Vlatch seriously. "After all, your scheme is only a long shot; it's illegal; it means to these companies an enormous expense with very doubtful results. How are you going to persuade them?"

"Men can't all be fools", said Barlick. "I'll keep at them until they give in. Good heavens, they must see it's the only way out! Some of them were thinking of trying out my invention before this happened; they saw it was a good thing. The only factor against us is time. How long will the Venerians take to erect their apparatus? I know it will take months to prepare mine, no matter how fast we work."

"And it may take months to get through the initial persuading and arguing", added Vlatch gloomily.

"We'll bring them round to it", said Barlick. "This sale must be cancelled, and I for one will fight it with every ounce of energy I possess."

@@@@@@@@@@

In the dimness before dawn the structure on Mount Chester looked weird and menacing. Vlatch, standing in the grounds of Dill Observatory after a sleepless night, gazed wearily at the strange bulk. He was moody and depressed. It had been cloudy for some time and he had not been able to complete the series of lunar observations on which he had been engaged. In normal times it would simply have meant waiting for four weeks until the moon was in the same phase again, but now - well, in four weeks' time there would very likely be no moon. That very evening was zero hour for the start of the Venerian activities.

There was no sound from Mount Chester. If the giant apparatus which now towered high into the morning sky had actually started to work, it gave no sign. And yet there was something unusual going on for the little coloured men, who for ten months had been labouring at the building of the machine, were hastening about in evident excitement. Vlatch could see them scaling ladders on the sides and crawling minutely along catwalks high on the bulk. For a time he hoped that the activity betokened something wrong with the machinery, some flaw in the scheme.

Suddenly the telephone rang. Dr Vlatch went in to answer it. The call was a long distance one he had asked for the previous evening. When he was connected Barlick's greeting came to his ear.

"How are things, Barlick?" he asked. "They seem to be all set here."

"Not so good, Vlatch", answered Barlick in a worried tone. "Two stations haven't finished yet with the changeover to the new machinery and heaven knows when they will. Without the full force it would be useless to start."

"They'll be working at top speed, don't you worry", replied Vlatch, keeping his voice cheerful while through the window his eyes gloomily scanned the apparatus on the hill, now clearly visible in the spreading dawn. A cordon of light-armed soldiers was drawn round the base of the hill, and even at that hour a crowd was gathered in the valley. Their angry cries came faintly to Vlatch across the distance.

"The changeover must be finished in time", he continued, turning his glance away. "You've done a wonderful job as it is, persuading seventy per cent of the American stations to come in with you. Are you sure the power will be enough?"

"Should be!" came back Barlick's voice. "I had planned to get this done before the Venerians started their operations. Once they begin we'll have too little time to negotiate with Best. I may have to risk it yet without these two stations."

"Well, I can only wish you all the best", said Vlatch uncertainly. He could not rid his mind of the fear that even now it was too late. Surely the Venerians would never agree now to cancel the sale when they had gone so far with their preparations? Yet if Barlick still clung to hope, and had even persuaded most of the tidal stations to adopt his plan.

"How's the war news?" asked Barlick.

"Not bad; we're holding our own in the Yangtze sector", said Vlatch. "But it looks like being a long war with China and Europe lined up against us."

He heard Barlick's sigh over the miles from distant South America. They spoke for a few more minutes, and then Dr Vlatch hung up and went with halting steps to the library where some computations awaited him.

Within three days the lunar apparent diameter was perceptibly less - perceptibly, that is, to careful measurement. At the end of the first week, the astronomers announced that the moon's distance, formerly 240,000 miles, was now 320,000 miles. Two days later it was 350,000 miles. Everyone could see that the moon was smaller. And as the actual fact came home to the world, the first protest was surpassed by the cries of indignation and fury that went up all over the world. Preachers denounced it as blasphemous; reformers as anti-social; financiers as ruinous and wicked. Many hailed it as the end of the commercial and maritime world, and predicted the return of man to savagery. Thousands saw with despair their work and hopes slowly retreating into space. Yet with what to most might seem a perverted loyalty to a bargain, detachments of police and still more soldiers held back the mobs that swarmed to Mount Chester intent on destroying the machine which was sending the moon out beyond the earth's control.

Life became almost impossible at the formerly secluded Dill Observatory, while Dr Vlatch's famous 78" reflector was nearly destroyed in its dome by ignorant hordes who mistook it for the Venerian machine.

During all that week, while the crowds round Mount Chester swelled, there was no word from Barlick. Then, on the eighth day, a Sunday evening, abruptly the whole globe was shaken by a gigantic explosion. Seismographs all over the world leapt as the earth trembled and reverberated. The American continent suffered especially. In many towns, foundations shifted and buildings cracked and crashed. The Mississippi burst its banks and terrible floods devastated the country. Even in distant Europe, pictures and ornaments mysteriously tumbled down. Over the entire earth there was darkness at noonday as enormous clouds of dust filled the atmosphere and almost obscured the sun, which appeared only as a dim, red disc. "Some immense volcano in the Amazon basin has burst forth", said the scientists. "It's those damned Venerians!" cried the rest of the world. "They're causing this by taking away our moon! Who knows what terrible disaster may happen next?" The threatening crowds round the Venerian camp multiplied until the guard had to be reinforced by a hundred of Best's steel robots.

Only Vlatch guessed the truth. Barlick brought confirmation when he arrived at the observatory two days later.

"We had to risk it without one of the stations, after all", he said. "But it came off, as you see. I have sent word to Best, warning him that the world will not allow the sale, that we will destroy every ounce of X2 he imports. I've offered to see him whenever he wishes. So now we have only to await his reply."

Meanwhile the astronomers were announcing that the moon's rate of departure was slowing down. Vlatch and Barlick read the news, puzzled their brains, and went on waiting for Best's reply. Twelve days after the start of the operations the news came that the moon was no longer retreating. Was the halt only temporary? Or had the Venerians given up? Had they been intimidated by the menacing attitude of the crowds? Had sentiment or a sense of fairplay made them decide to cancel their purchase and leave the earth-people with the globe which they evidently cherished so much? These wild speculations, and others even wilder, appeared in every newspaper and blared over the radio, but they could not conceal the fact that nobody knew what was happening.

"It doesn't sound like the Venerians to give anything up out of pure kindness", Barlick said to Vlatch, as they studied the news. The moon now had not increased her distance for ten days. Astronomical opinion was that the Rho-ray had after all failed to work at such distance and that the transfer of the moon would be impossible. As time went on and the moon remained stationary, confidence in this view increased. But although no other explanation occurred to him, Barlick could not share the confidence.

In the midst of the excitement the two astronomers at Dill were among :the few who noticed a small news item announcing that the financier Harper G. Best had been assassinated by a mysterious assailiant; using a Venerian atom-gun, but thought from his dress to be a Martian. Barlick was quiet and thoughtful for a long time after reading it. But soon the urgency of the war swept away all other thoughts. The Venerians and their project faded from the minds of the earth-men.

@@@@@@@@@@

Barlick was at Dill on leave from the navy, where he was teaching recruits how to navigate, when he had a visit from his emerald-green Venerian friend. It was more than a year since the night of the explosion which had rocked the earth.

"We've given up all idea of transporting the moon back to Venus" said the little green man. "The power we are wasting is out of all proportion to any gains we might hope to make. We are cancelling the sale. Now that Best is dead there may be complications; we shall have to negotiate with his trustees, but we intend simply to block all credit at the Venerian end."

"Has your apparatus proved unsatisfactory?" asked Barlick. "It seemed infallible."

"Theoretically, we were infallible", said the Venerian. "Yet although we have several times dismantled and rebuilt the machine during the past year, we can find nothing that shows where we may have gone wrong. Yet the fact remains that the ray is not functioning. Well, we leave tonight for Venus. I will wish you goodbye, Mr Barlick."

I leave Dill tonight, too", replied Barlick. "My leave is up now - back into the thick of it again. So goodbye; I must go and look for Dr Vlatch."

"You did a good job of work that time", said Dr Vlatch when, a few hours later, they were standing on the platform of Dill Station, awaiting the train which would carry Barlick back to his post.

"What do you mean?" asked Barlick. 'I didn't do anything, I'm afraid. Perhaps we shall never know why the Venerians failed too; it was just a lucky chance."

"I could have told you right away", said Vlatch coolly. "But I didn't wish to speak while there was any danger of the Venerians getting to know. You did it all, you know, with your radio-beam."

"I don't understand - what did I do?" cried Barlick in surprise.

"Spoiled their little game, of course", answered Vlatch. "You know that their apparatus threw a narrow beam, which must be focussed with extreme accuracy. The slightest deviation, they told us, would ruin the venture. So you produced the necessary deviation, that's all."

"You mean, the explosion?"

"Just that", replied Vlatch. "A tremendous shock to the globe, such as the explosion of the X2 dump, is bound to do something to it. I've had a theory about that for a long time, and although the proof is not positive, I think you've fairly well confirmed it. My idea is that every big volcanic eruption produces an effect such as your explosion did, only on a slightly smaller scale. Your big bang knocked the earth's never very stable axis just the minutest bit out of its former position. Yes, the Venerians had allowed for precession, nutation, seasonal variations, everything; but not that. They couldn't know of it; our astronomers may not discover the minute difference for a long time. It may not even be measurable. But it was enough to alter the moon's apparent position to such an extent that the Rho-ray beam missed its objective. It's fortunate for us that the beam was so narrow."

"Then I'm really - I've actually saved the earth?" Barlick faltered, almost incoherent with excitement. "My plan wasn't a failure after all!"

"It succeeded in an unexpected way", said Vlatch. "We have the moon yet, the tidal stations are still able to work, and the power they can give will be even greater than before, since the new machinery will more than compensate for the loss of tidal force caused by the moon's retreat. Better still, the Venerians have done us astronomers a good turn. Since the moon is further away, her period of revolution is no longer equal to her period of rotation, and so at last we will so able to see the mysterious 'other side'. When peace comes again, the astronomers are going to have a really good time on that once-hidden side of our satellite. Even exploration will not give us such a good idea of it as observation with our best instruments."

Smaller, but still familiar, the full moon was rising opposite the sunset glow. Barlick and Vlatch raised their hands in a salute to her as the train glided in.

@@@@@@@@@@

written in the 1940s

|