|

My father could have been a rocket scientist if the secret police hadn't stuck their noses in.

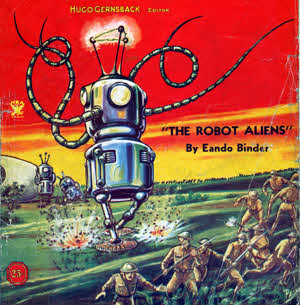

Harry Turner got the science and science-fiction bugs in his early teens, as proved by the surviving drawings made in imitation of his favourite artists in the American pulp magazines and a composition book from Class 4M at Ducie Avenue Central School For Boys in Manchester, and he wanted to live the dream. Harry Turner got the science and science-fiction bugs in his early teens, as proved by the surviving drawings made in imitation of his favourite artists in the American pulp magazines and a composition book from Class 4M at Ducie Avenue Central School For Boys in Manchester, and he wanted to live the dream.

My Turner grandmother, who was our next-door neighbour by then, told me at the time of the Moon landings that she and my grandfather had always treated young Harry's interest in spaceflight and voyages to other planets with amused scepticism. But seeing it happen live on television in 1969 had turned her into a believer.

Many others shared this dream, including the members of the British Interplanetary Society. And when local rocketry enthusiasts formed a Manchester Interplanetary Society in 1936, my father had to join them. Over a dozen teenagers, mainly boys, built solid-fuel rockets costing 6d to 1/-, set them off in the wide-open spaces of Clayton Vale and imagined that they were pushing back the frontiers of science.

Then everything went horribly wrong.

A large crowd turned up to some Saturday test launches at the end of March in 1937, failed to observe the society's safety limits and got too close to rockets which went "Bang!" rather than "Whoosh!" This didn't matter too much if the cases were made of paper, but one of the rockets had an aluminium shell. Which went off like one.

Result: one young schoolboy with a minor injury to his leg, lots for the Sunday newspapers to write about, the heavy hand of an Inspector Smith of the "Explosives Department" [Smith? Really?] descending on the MIS, and entirely inappropriate charges under the Explosives Act (1875).

Eric Burgess, one of the Society's founders, argued in court that they were hoping to "further the use of rockets for commercial purposes" and the main object of the Society was "to try to communicate with other planets by means of projectiles", rather than to give pyrotechnic displays.

In the absence of expert technical opinion, the magistrate had to give the Society the benefit of the doubt and the charges were dismissed. Banned from making more rockets, Eric Burgess and some others formed a breakaway group—the Manchester Astronautical Association—to design spaceships. The remaining members of the MIS turned to SF fandom. ■

I could have been the son of a commercial artist like my mother's uncle, the Glasgow artist Robert Eadie.

But the Germans failed to bomb the building housing the latest version of my father's war service registration documents in 1942, as they had done in the Xmas blitz of 1940 and again the following May. Which meant that he no longer had to stay up all night, being an air-raid warden; a relief which my mother (to be) was not able to share.

My father's youthful interest in science included astronomy, and he joined the Junior Astronomical Association (JAA), which had been founded in Glasgow by Marion Eadie and her friend Jean Harris. My father was the editor of The Astronaut, the journal of the MIS, and he soon became a contributor to Urania, the JAA journal, and then the society's treasurer. A growing correspondence between Manchester and Glasgow led to friendship, and my parents-to-be had their first meeting at the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow.

My father did well at school but he was always destined for the world of work at 16, which meant that he had money of his own and he was able to travel to Leeds and London to meet other SF fans, and to Glasgow to combine JAA business with pleasure.

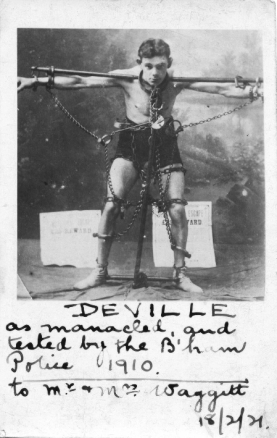

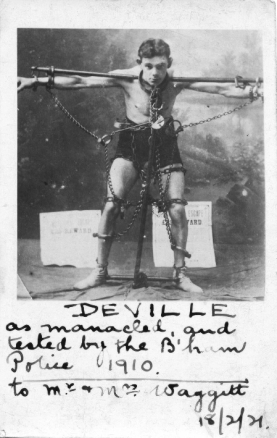

He was the son of Barton Turner, an escapologist and illusionist, who performed as The Great Deville in Britain's music halls. Barton had married Lucy Parker, who had five sisters and two brothers. The Turners and Parkers were real show-biz families. One of Barton's brothers, Percy, became a theatrical producer, one of Lucy's sisters was a Tiller Girl and another, Pat, featured in "Barton Productions" as Mdlle. Victoire, who was chopped into 12 pieces on stage! He was the son of Barton Turner, an escapologist and illusionist, who performed as The Great Deville in Britain's music halls. Barton had married Lucy Parker, who had five sisters and two brothers. The Turners and Parkers were real show-biz families. One of Barton's brothers, Percy, became a theatrical producer, one of Lucy's sisters was a Tiller Girl and another, Pat, featured in "Barton Productions" as Mdlle. Victoire, who was chopped into 12 pieces on stage!

I think my father was a little embarrassed by having The Great Deville as his dad but he was persuaded by my own interest, and that of people researching the history of magic like the TV producer John Fisher and the author Professor Edwin Dawes, that Henri Deville was someone to celebrate.

My grandparents rented a large house in Victoria Park, Manchester, and the double attics had become a clubroom for rocketeers. With the decline of the MIS, the Turner home became a meeting place for science fiction fans in the Manchester area and visiting fans from the main centres of fandom: Leeds, Liverpool and London.

When my father joined the Science Fiction Association, he was soon recruited as the cover artist for the journal, Novae Terrae. His expertise in the art of drawing directly onto wax stencils soon led to requests from the editors of other fan mags, such as Futurian War Digest. He even sent cut stencils across the seas to 4sj Ackerman, who could provide a much higher class of stencil than his British counterparts.

After meeting Walter Gillings, editor of the British prozine Tales of Wonder, at the April 1938 London fan convention, my father began to produce small illustrations for him; despite resistance from a cost-cutting publisher. When a rival, FANTASY Thrilling Science Fiction, appeared, he was invited to contribute to that, too. His freelance work also included designing book jackets for the publisher Lloyd Cole. The next logical step was doing some publishing on his own account.

He had contributed odd pages to FWD, but he just had to "pub his own ish". Zenith was duplicated on a battered old Roneo, which his father had acquired for printing lists, and which my father found could be used to create multi-coloured text and artwork. After five issues, a promising career as an artist and publisher shuddered to a halt when the RAF sent out call-up papers—just as my parents-to-be were about to get married. ■

My mother might have been really big in publishing: she had the soon-to-be legendary Arthur Clarke writing for her at one point.

Or she could have been a famous science-fiction author if my her career had not been blighted by the paper shortages caused by World War II. (Thanks very much, Mr. Hitler!) Everything seemed to be going so well when Beast of the Crater by Marion F. Eadie appeared in issue 16 of Tales of Wonder. There was not to be an issue 17. "Not to be" had become the fate of most science-fiction publications by then.

My mother's parents were Jenny and William Eadie. My Scottish grandfather, an engineer, went to America [he is reported to have arrived in San Francisco the day after the earthquake] and did quite well for himself. He returned to Glasgow at the outbreak of the First World War, and went to work in the shipyards when he was declared too old for military service. My English grandfather, a dozen years younger, was recruited into the Manchester Regiment and served as a reservist, being demobbed as an acting sergeant in 1919, which allowed him to bill himself as The Wizard of the Army when he resumed his performing career.

Cross-over between science and science fiction meant that my mother knew many English SF fans and young rocketeers, including Arthur Clarke and Eric Burgess, and they persuaded the president of the JAA and editor of its journal to start and astronautics section in Urania. Although she has told me that she was always more interested in the science than the fiction, it was inevitable that my mother would become involved in my father's fanzine Zenith when she moved to a job in Manchester in the early years of World War II, and that she would start writing science fiction as well as science fact articles on astronomical themes.

It was a rush job, but the wedding went ahead before the RAF could kidnap my father and send him to Redcar for basic training. After a six-month radio course at Birmingham College of Technology, my father was posted to RAF Yatesbury early in 1943, where he was reunited with Corporal A.C. Clarke, who was destined for officer training. In the meantime, Corporal "Spaceship" Clarke was entertaining the troops with talks on rocket propulsion and gramophone concerts of Classical music.

As a qualified radar technician, my father's job was to service radar installations along the south and east coasts; the front-line of the defence against German bombing raids. When that threat was over, the RAF decided to send him to India to counter the threat from Japan. One small snag: by the time father-of-one Harry Turner's troop-ship reached Bombay, the Japanese had surrendered.

The newly installed Labour government decided not to bring the troops home quickly; perhaps in the hope that they would deter the ambitions of the locals, who were expecting to become independent and say goodbye to the British Raj. Stuck 6,000 feet up a mountain in Tamil Nadu, my father and his colleagues were left with their minds boggling when they learnt that the rest of the RAF in India had actually gone on strike over the delay in repatriation!

My father recalled that one of his comrades climbed the mast of the radar aerial to hang up a token red handkerchief, but life out in the wilds went on pretty much as normal until they were allowed to return home. ■

I could have been writing this with an Aussie accent: my father's Aunt Janet offered to take him under her wing on the other side of the planet after the war.

The Parker migrants from my grandmother's family had done rather well for themselves and one of her brothers served a term as mayor of Ringwood, a suburb of Melbourne. Luckily for British SF fandom, my father decided that he would be expected to accept Aunt Janet's guidance, as far as his career went, and he opted for independence in England.

Before the war, my father was a rubber chemist at the Anchor Chemical Company in Clayton, Manchester. He returned there but, in search of a better working environment, he went to work at Redfern's Rubber Works in Hyde, Cheshire, where he created and managed an advertising department, and he moved the family to Romiley, three miles away. The change came at a time when my father was contributing artwork to prozines like Nebula and Science Fantasy, and he had dipped back into the world of fandom.

The local fan group in Manchester had asked for his help with their fanzine, Astroneer, which was foundering. My father had also produced a sixth, rather unsatisfactory issue of his own zine, Zenith, and he had taken on the job of producing a combozine for the legendary 1954 SuperMancon. Better was to come.

His old friend Eric Needham and my father unloaded on an unsuspecting world, a magazine entitled Now & Then, which featured the art and design skills of Harry Turner and the imaginative writing of Eric Needham, the creator of the much imitated Widower's Wonderful range of products and the author of many fascinating flights of fancy.

Some of the early editorial meeting took place at the home of my grandparents, as Eric Needham was also living in Longsight, and my father was usually careful to take one of the three lads; Philip, William or Robert; along to visit the grandparents and provide an "alibi" for his not being able to enjoy a return trip to Romiley on the back of Uncle Eric's motorbike. The lads also provided a workforce when the magazine was being produced, as the photograph shows. Quite how P.H.T. managed to skive off duplicating duty is not known. Some of the early editorial meeting took place at the home of my grandparents, as Eric Needham was also living in Longsight, and my father was usually careful to take one of the three lads; Philip, William or Robert; along to visit the grandparents and provide an "alibi" for his not being able to enjoy a return trip to Romiley on the back of Uncle Eric's motorbike. The lads also provided a workforce when the magazine was being produced, as the photograph shows. Quite how P.H.T. managed to skive off duplicating duty is not known.

Looking back, we lads were not really involved in our father's second dip into fandom; apart from service at the printing works. We were aware of visits by the two Uncle Erics—Needham & Bentcliffe—but they were involved in adult things with our father and we were busy with kids' things. There was a legacy, however.

When my father gaffiated at the end of the 1950s, he got rid of lots of fannish stuff and I acquired a small collection of Nebulas, some bound copies of Astounding, Wonder Stories and Armchair Science, and a scattering of other SF magazines, which formed the nucleus of my own collection. There were also copies of some of the magazines which my father had created; treasures which he was able to rediscover in his retirement years when he was asked to help the likes of Rob Hansen chart fannish history in the early years.

As a teenager, I was buying half-crown SF paperbacks; and showering curses on the publishers who charged 3/6d for a product of the same size. I was able to buy novels by Ken Bulmer and think to myself: "My Dad knows the bloke who wrote this!" Same with Robert Bloch, Eric Frank Russell, John Christopher, et al.

Although officially out of fandom, my father took the opportunity to visit fannish friends on trips to art exhibitions in London, particularly the Bulmers and the Varleys. He had been recruited by the Manchester Guardian and Evening News by then, and he was busy organizing and managing the advertising department at the Evening News.

He was inveigled back into active fandom in the 1970s by his old friend and near neighbour Eric Bentcliffe, and he soon re-established his reputation as one of the top artists in the field, particularly with the work done for Lisa Conesa's award-winning zine Zimri when he was experimenting with silk-screen printing. He also created an impressive wraparound cover for Maya #8 (1975) by combined his interest in that ancient South American civilization with his design talents. ■

The world is full of secret societies. I know, my father and I both created our share.

The creator of the Romiley Fan Veterans & Scottish Dancing Society was somewhat bemused by his No. 1 son's enthusiasm for creating other Romiley-based organizations, but he was soon placing his own orders for Able Labels for the likes of the Thelonious Monk Appreciation Society (which Mr. Able thought was something to do with The Lonious Monk at his first attempt) and the Septuagenarian Fans Association. It was invention and re-invention in action.

And when my father was let loose on my Viking Direct catalogues, he had no problems with creating his own division of my outfit, Henry T. Smith Productions, to take advantage of bargain offers and next-day delivery when we both got involved with computers and desk-top publishing in a serious way.

My father felt that fannish preoccupations tend to be repetitive over the years—a little exposure to it goes a long way and it is possible to get along very well without it. Outside fandom, after dealing with life's necessities like earning a living to support a family and a mortgage, my father concentrated his interest (and most of his spare cash) into drawing, painting and music, and such-like cultural areas.

He accumulated an art-history library and a record/tape collection of jazz and classical music, which managed to overflow the storage space available in two adjoining houses, which were forever decorated with GUPs (Great Unread Piles) of books.

We both shared a passion for Classical music, which is universal and eternal. He was a big jazz fan. I can see the point of it but I prefer the noises of rock and electric folk. The contemporary music of my yoof did nothing for my father. And I can see his point via my complete indifference to the current pop scene.

The Turners didn't get a TV until I was well into my teens, which helped to establish my reading habit. I tend to buy books to keep a few unread ones available. My father was always working to create his own personal reference library. He enjoyed surrounding himself with knowledge on a serious scale.

He was amused at first when I resigned from a book club, which was getting repetitious in its catalogues, only to rejoin a few months later to take advantage of an introductory offer of books at 1p each, using the house next door as my address. Then he realized that it was a good idea. And that's how, in part, he managed to fill next door with books. But only after a serious disruption in his life. ■

Not being able to see has to be the worst thing that can happen to an artist.

My parents acquired the house next door (the other half of their semi-detached residence) in 1956 as a home for my grandparents. My English grandfather was then registered as blind following retinal detachments after cataract operations, but he still had limited vision.

My Scottish grandmother died at the beginning of 1956, five years after her husband. A couple of months later, the other half of the Turner semi come onto the market. My father made an offer for it but the house had to be sold by public auction. So my parents got it for less than the price they'd offered! Suddenly, the Turner family was united again—in adjacent houses in Romiley rather than in the one big house in Victoria Park.

Twenty years later, after the death of my English grandmother (five years after her husband), my father decided not to sell the house next door right away as it offered spare bedrooms for visiting sons and their friends, and working space. My mother resumed her writing career in the ground-floor front room, writing hundreds of scripts for the girls' magazines published by D. C. Thomson. My father acquired a studio in the bedroom above.

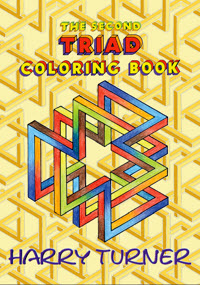

He was exhibiting paintings locally in Stockport and Manchester, and at the John Moore's in Liverpool. When he got to know Hayward Cirker of Dover Publications of New York, he soon had a number of contracts for books of designs on a range of topics. He beat me by five years when it came to selling a book to a commercial publisher. And he did it under his own name. He'd sold some artwork under an alternative identity (Henry Ernst) in the 1950s but he never went in for my serial level of alter egos.

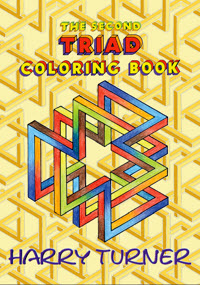

Triad Optical Illusions and how to design them was published in 1976 and reprised in 2006 as a colouring book with the technical stuff peeled off. My father offered Dover a second volume of Triad designs. Not a dicky bird back from the decision makers despite several prompting emails. So Triads #2 eventually became a posthumous "publish it yer bluddy self" effort. So it goes. (Vonnegut, P.K. Dick, Kim Stanley [boring] Robinson, H.G. Wells, EandO Binder, lots of Eastern European authors—my father read them all.)

Triad Optical Illusions and how to design them was published in 1976 and reprised in 2006 as a colouring book with the technical stuff peeled off. My father offered Dover a second volume of Triad designs. Not a dicky bird back from the decision makers despite several prompting emails. So Triads #2 eventually became a posthumous "publish it yer bluddy self" effort. So it goes. (Vonnegut, P.K. Dick, Kim Stanley [boring] Robinson, H.G. Wells, EandO Binder, lots of Eastern European authors—my father read them all.)

But his reading was to be interrupted. The lights were going out for him as he approached fifty and his cataracts worsened. It was a very gradual process, and he was able to adapt at work and at home, but he eventually found himself unable to see well enough to paint and draw, to work on publishing contracts beyond his book on Triads, and to read or watch television. Paradoxically, photography was about all that he could manage with the right equipment.

Somewhat less than perfect, vision-restoring operations allowed my father to re-engage with life in the early 1980s; if forced to juggle pairs of specs. He was able to resume reading and he included science fiction in his extensive programme of book-buying (to the relief of his book clubs) He enhanced his reputation for knowing something about almost everything and he had books in his personal library to back up his views. He was also able to resume offering artwork to fanzines.

My father retired from his management job at the Manchester Evening News in 1985 but continued professional free-lance work for local newspapers and free-sheets in addition to his good works on the design side for the likes of the British Journal of Russian Philately, Enemy News (the Wyndham Lewis Society's organ) and the editors of a range of small press magazines.

My parents were enthusiastic walkers in their younger days, but "trudging" was never some thing which gladdened the hearts of their offspring, either around West Kilbride on holidays with our Scottish grandmother or closer to home in the Peak District. But it did turn out to be something which we lads incorporated into our later lives. My parents were enthusiastic walkers in their younger days, but "trudging" was never some thing which gladdened the hearts of their offspring, either around West Kilbride on holidays with our Scottish grandmother or closer to home in the Peak District. But it did turn out to be something which we lads incorporated into our later lives.

After he retired, my non-motorist father used to enjoy a 3-mile walk along the Peak Forest canal to Marple to order wine at Peter Dominic and I [used to] find myself walking distances calculated to send motorists rushing for their car keys. Robert trudged from one side of England to the other year (in 2 episodes), and Bill also goes wandering around with his camera. So maybe the practice did us some good. ■

My father tended to have philosophical issues with computers at first. That was never a problem for me.

I saw owning PC as something to help with work but mainly as a means of delving deeper into my own well of creativity. My father retired from the MEN as computers were taking over on the design side, having ended the hot-metal era on the production side. It was probably the lack of physical contact between artist and output that put him off, but that changed as we got better and better computers.

By the mid-1990s, companies were retiring 386 PCs in favour of 486s, and there were plenty of bargains available to run DOS versions of WordPerfect quite comfortably with a collection of the newly available TrueType and Bitstream soft fonts, and a laser-printer. Whenever my father got stuck with "WordPerf", his first response was to apply Eric Needham's philosophy of enlightened empiricism to the goal of making the machine do what he wanted it to do. He enjoyed a surprising degree of success, and he knew that he could always call on the Computer Guru for some free tech support if E.E. wasn't enough.

Acquiring a scanner and an inkjet printer did wonders for his correspondence, letting him add colour, images and fancy typography to his correspondence, such as his Odds & Sods bulletins to the Varleys, which ran to over 200 episodes over the years. He was also able to rework typewritten memoirs, recycling fanzines on authentic-looking green paper from Mr. Viking, and use software which offered new ways to manipulate images.

There were times in the 1970s and 1980s when my parents and I would all be battering away at typewriters. As the new century approached, we were still writing furiously, but the three keyboards were now connected to computers, and my father was delighted to have one which could play CDs whilst he worked. ■

My father is an earthquake survivor. Well, we all are! Who says nothing ever happens in Romiley?

The one that made the biggest impression on my mother was the Quake of the Century in 1984, when she saw my father's much-prized 1976 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica rippling on its shelf. The one that made the least impact came at 1 a.m. in February of 2008.

It woke me up and my father was worried that it was going to chuck him out of bed. My mother managed to sleep right through it, as she had slept through the passage (which alarmed everyone else in the building) of a German V1 buzz-bomb right over the hotel in Lincolnshire where my parents were spending my father's weekend leave.

The quake that impressed my father most took place one lunchtime in October 2002. He was on duty in the kitchen and he was treated to the sight of a pan of soup sliding a couple of inches across the gas stove and off its position directly above the burner.

When not distracted by the antics of the ground beneath our feet (or beds), Romiley's astronomers have kept a close eye on the sky. My parents and I have turned out en masse to watch Mir and the ISS go over us, and brilliant flares from Iridium satellites.

We always hoped to see a decent comet but Halley's Hoax was a total flop in 1986. We did see Comet Hyakutake in 1996. Hale-Bopp the following year was the only decent one visible in the northern hemisphere in the second half of the 20th century. We have also viewed our share of total lunar eclipses, but never seen the Moon turn blood red, as the newspapers the next day invariably claim.

Eclipses of the Sun are always partial when seen from Romiley, but my parents were lucky enough to get a good deal from the Guardian for a cruise to see the 1973 total eclipse off the Canary Isles, and watch Patrick Moore and his TV crew in action. And my mother organized a pilgrimage to Penzance for the three of us to view the 1999 total eclipse; which was clouded over both for us and for Patrick Moore, who was nearby. So that's one-all in total eclipses for my parents and 0-1 for me.

The other Big Event for the astronomers was the transit of Venus in 2004. My mother had been looking forward to seeing that for most of her life but, pessimists that we are, we were resigned to cloudy skies on the great day. Wrong! The Universe smiled on us, and so did the Sun.

We had looked out the eclipse viewers but I found that I could use one leg of her binoculars to project a solar disc onto a white card, and we were able to follow the progress of the clearly visible black dot across the disk. I even managed to take a few photographs before it was too late. Sadly, only my mother and I were able to follow the 2012 transit, and we had to do it via an Internet transmission from a NASA website in Hawaii.

A stroke in his 85th year wiped out most of my father's memories of his fannish years—a source of great regret to him—and his health declined in his final two years. Watching his horizons shrink was a grim reminder of what lies in store for anyone who reaches serious old age. But Harry Turner will be remembered a man of many ideas and enthusiasms, which he enjoyed sharing with others.

He could turn his hand to most practical matters; home printing with a duplicator, maintaining valve hi-fi equipment and all types of construction work, including building custom items of furniture. He was also a keen gardener and garden sculptor in his younger days, and he became a master of calligraphy as a means of improving his handwriting.

Some four years after his death, as I continue to explore the documents and artwork that he left behind, my understanding of what he achieved continues to grow, and I continue to hope that, some day, I'll have knocked more of it into a publishable form. ■

Philip Turner, April MM13

Quotations were taken from the writings of H.T. unless otherwise indicated.

Originally drafted for Peter Weston's Relapse in 2013 but things have changed a lot since then

|

Harry Turner got the science and science-fiction bugs in his early teens, as proved by the surviving drawings made in imitation of his favourite artists in the American pulp magazines and a composition book from Class 4M at Ducie Avenue Central School For Boys in Manchester, and he wanted to live the dream.

Harry Turner got the science and science-fiction bugs in his early teens, as proved by the surviving drawings made in imitation of his favourite artists in the American pulp magazines and a composition book from Class 4M at Ducie Avenue Central School For Boys in Manchester, and he wanted to live the dream. He was the son of Barton Turner, an escapologist and illusionist, who performed as The Great Deville in Britain's music halls. Barton had married Lucy Parker, who had five sisters and two brothers. The Turners and Parkers were real show-biz families. One of Barton's brothers, Percy, became a theatrical producer, one of Lucy's sisters was a Tiller Girl and another, Pat, featured in "Barton Productions" as Mdlle. Victoire, who was chopped into 12 pieces on stage!

He was the son of Barton Turner, an escapologist and illusionist, who performed as The Great Deville in Britain's music halls. Barton had married Lucy Parker, who had five sisters and two brothers. The Turners and Parkers were real show-biz families. One of Barton's brothers, Percy, became a theatrical producer, one of Lucy's sisters was a Tiller Girl and another, Pat, featured in "Barton Productions" as Mdlle. Victoire, who was chopped into 12 pieces on stage! Some of the early editorial meeting took place at the home of my grandparents, as Eric Needham was also living in Longsight, and my father was usually careful to take one of the three lads; Philip, William or Robert; along to visit the grandparents and provide an "alibi" for his not being able to enjoy a return trip to Romiley on the back of Uncle Eric's motorbike. The lads also provided a workforce when the magazine was being produced, as the photograph shows. Quite how P.H.T. managed to skive off duplicating duty is not known.

Some of the early editorial meeting took place at the home of my grandparents, as Eric Needham was also living in Longsight, and my father was usually careful to take one of the three lads; Philip, William or Robert; along to visit the grandparents and provide an "alibi" for his not being able to enjoy a return trip to Romiley on the back of Uncle Eric's motorbike. The lads also provided a workforce when the magazine was being produced, as the photograph shows. Quite how P.H.T. managed to skive off duplicating duty is not known. Triad Optical Illusions and how to design them was published in 1976 and reprised in 2006 as a colouring book with the technical stuff peeled off. My father offered Dover a second volume of Triad designs. Not a dicky bird back from the decision makers despite several prompting emails. So Triads #2 eventually became a posthumous "publish it yer bluddy self" effort. So it goes. (Vonnegut, P.K. Dick, Kim Stanley [boring] Robinson, H.G. Wells, EandO Binder, lots of Eastern European authors—my father read them all.)

Triad Optical Illusions and how to design them was published in 1976 and reprised in 2006 as a colouring book with the technical stuff peeled off. My father offered Dover a second volume of Triad designs. Not a dicky bird back from the decision makers despite several prompting emails. So Triads #2 eventually became a posthumous "publish it yer bluddy self" effort. So it goes. (Vonnegut, P.K. Dick, Kim Stanley [boring] Robinson, H.G. Wells, EandO Binder, lots of Eastern European authors—my father read them all.) My parents were enthusiastic walkers in their younger days, but "trudging" was never some thing which gladdened the hearts of their offspring, either around West Kilbride on holidays with our Scottish grandmother or closer to home in the Peak District. But it did turn out to be something which we lads incorporated into our later lives.

My parents were enthusiastic walkers in their younger days, but "trudging" was never some thing which gladdened the hearts of their offspring, either around West Kilbride on holidays with our Scottish grandmother or closer to home in the Peak District. But it did turn out to be something which we lads incorporated into our later lives.