| Things To Come | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

|

A Street in Everytown : the year 1940. EVERYTOWN is every town. It is backed by a very characteristic skyline of hills which recurs throughout the film to remind us that we are following the fate of one typical population group, and it has a central " place," a big Market Square with big hotels, public buildings, cinemas, kiosks, statuary, tramways, etc. First, there is a general view of Everytown from a crest above it. In the foreground we see workers going down the hill into the town and down the hill we see the whole of Everytown, suburbs, and Central Square together; it is a clear Christmas Eve. Then we come to the Central Square in Everytown. It has features recalling Trafalgar Square or a big town Market Square or a French Grand Place. There is a confluence of trams and buses. The Christmas traffic is active. On one of the chief buildings the moving light sign of a newspaper flashes the latest news. " Europe is arming . . . ." The camera moves up from the traffic of the Square to this light sign: " Alarming speech by Air Minister—" Big shop window full of Christmas toys. Children and mothers admiring. A bus stops and people get out of it. On the bus one sees the usual newspaper posters with a glaring headline about the dangerous international situation. " Straits dispute. Acute situation." The entrance of a tube station. The usual traffic. A newsvendor stands at the entrance. His placard reads: " Another 10,000 aeroplanes." But he shouts, " All the winners." In a bus a young girl opens her paper and glances through the first page, which is full of headlines talking about the war danger. During all these scenes Christmas shoppers and people with packages pass to and fro. It is a peaceful and fairly happy Christmas shopping crowd. Nobody appears to be affected imaginatively by the war danger. The voice has called " Wolf " too often. Only the camera calls attention to the brooding threat.

Call to Arms

THE scene changes to one of Everytown's scientific laboratories. Young Harding, a student of two and twenty, is working intently. It is a small, reasonably well-equipped municipal school laboratory looking out on the Central Square. It is a biological, not a chemical, laboratory. Through the open window comes the bellowing of the newsvendor. " War crisis ! " Harding listens for a moment : " Damn this war nonsense." He closes the window to shut out the sound. He looks at his watch and sets himself to put things away. At first he is wearing a neat laboratory overall. This he takes off. He goes out into a suburban residential road with little traffic. There are many pleasant detached homes. Harding approaches a house through a garden gate. He walks into the rather dark study where John Cabal is musing over a newspaper. The furniture of the room indicates his connection with flying. There is the blade of a propeller over the mantel shelf and a model on the shelf. On the table are some engineering drawings partly covered by the newspaper. Cabal's arm, with wrist-watch, is resting on the evening paper. He has a habit of drumming with his fingers which is shown here and again later. The camera comes up to the hand and paper. The headlines show : " EVENING NEWSLETTER "

Cabal ponders. He looks towards the door. Harding approaches Cabal. He sees the paper and the headlines. Cabal: " Hullo, young Harding You're early." Harding: " I had finished up. It was too late to begin anything fresh. Why are the newsboys shouting so loud? What is all this fuss in the papers to-night, Mr. Cabal?" Cabal: " Wars and rumours of war again." Harding: " Crying wolf ?" Cabal : " Some day the wolf will come. These fools are capable of anything." Harding: " What becomes of medical research in that case?" Cabal: " It will have to stop." Harding: " That will mess me up. It's pretty nearly all I care for. That and Marjorie Home, of course." Cabal : " Mess you up ! Of course it will mess you up. Mess up your work. Mess up your marriage. Mess everything up. My God, if war gets loose again. . . ." Cabal and Harding turn towards the door as Passworthy walks in. Passworthy : " Hullo, Cabal ! Christmas again ! " (Sings.) " While shepherds watched their flocks by night, All seated on the ground. . . ." Cabal nods at the paper. Passworthy takes it up and throws it down with disdain. Passworthy : " What's the matter with you fellows ? Oh, this little upset across the water doesn't mean war. Threatened men live long. Threatened wars don't occur. Another speech by him. Nothing in it. I tell you. Just to buck people up over the Air Estimates. Don't meet war half-way. Look at the cheerful side of things. You're all right. Business improving, jolly wife, pretty house." Cabal : " All's right with the world, eh? All's right with the world. Passworthy, you ought to be called Pippa Passworthy.. . .. " Passworthy : " You've been smoking too much. Cabal. You—you aren't eupeptic . . ." (Walks round and sings.) " No-el ! No-el! . . ."

LATER the scene is the suburban road outside John Cabal's house. Various clocks—one after another —are heard striking midnight. Cabal's door opens. Cabal, Mrs. Cabal, Harding, and Passworthy come out. Christmas bells are heard. A faint thud. Everybody is silent for a moment. Mrs. Cabal : " What was that ? It sounded like a gun." Passworthy : " No guns about here Merry Christmas, Cabal—good luck to us for another twelvemonth. The last wasn't so bad. Here's to another year of recovery." Suddenly searchlights appear in the sky silhouetting the hill crest. The group at the door observe the searchlights and turn questioningly towards one another. Mrs. Cabal : " But what are searchlights doing now ? " Passworthy: " Anti-aircraft manoeuvres, I expect." Cabal : "Manoeuvres ! At Christmas? No !" Three thuds rather louder mingle with the pealing bells. Harding: " Listen ! Guns again." The bells cease abruptly. The sound of distant guns becomes quite distinct. The group—mute suspense. Heavy concussion heard. After this the noise subsides as though the trouble was drifting away from Everytown. Nobody speaks. From the study the telephone rings. Cabal turns and hurries back into the house. From the house there comes Cabal's voice: "What, to-night—three o'clock at the Hilltown hangar? I'll be there." Cabal comes out again to the listening group. " Mobilisation !" Mrs. Cabal : " Oh—oh. God !" Passworthy : " Perhaps it's only a precautionary mobilisation." Cabal turns and goes into the house. The others follow. In Cabal's study the group listen to a radio announcer. Radio : " The unknown aircraft passed over Seabeach and dropped bombs within a few hundred yards of the waterworks. They then turned seaward again. By this time they had been picked up by the searchlights of the battleship Dinosaur, and before they could mount out of range she had opened upon them with her anti-aircraft guns. Unfortunately without result." Passworthy : "That's—that's alarming, certainly." Harding: " Of course everyone has said, 'This time there will be no declaration of war.' " Mrs. Cabal : "Listen !" The radio resumes, crackling: " We do not yet know the nationality of these aircraft, though, of course, there can be little doubt of their place of origin. But before all things it is necessary for the country to keep calm. No doubt the losses suffered by the fleet are serious. " And it is imperative that the whole nation should at once stand to arms. Orders for a general mobilisation have been issued and the precautionary civilian organisation against gas will at once be put into operation. Ah—instructions have come to hand. We shall cut off for five minutes and then read you the general instructions. Please call in any friends. Call in everyone you can." They all look at each other. Passworthy (to Harding) : " I suppose we shall find our marching orders at home. Nothing to do now but get on with it." Mrs. Cabal : " War ! God help us all."

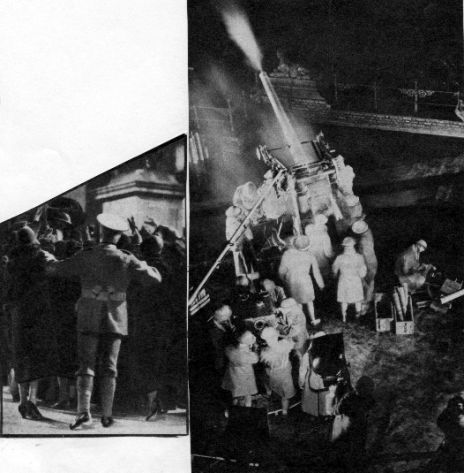

THE Centre Square of Everytown. Large anti-aircraft on truck comes into Square. Searchlights being mounted on a roof. Electric signs going out. Special service men in badges herding people to shelter. Belated straggler running across the Square. Searchlights break out. Anti-aircraft gun being loaded by the light of a carefully-shaded lamp. Faces of the gunners seen closely. All this is to be very quick and furtive. As lights go down the lighting changes to silhouette effects and the sounds diminish until at the end there is absolute silence. The scene changes to the nursery at Cabal's home. Cabal is buttoning on his airman uniform. He looks at the sleeping children. He turns his head, tormented by the thought of their future. Mrs. Cabal: " My dear, my dear, are you sorry we—had these children?" Cabal thinks long. " No. Life must carry on. Why should we surrender life to the brutes and fools ?" Mrs. Cabal : " I loved you. I wanted to serve you and make life happy for you. But think of the things that may happen to them. Were we selfish?" Cabal draws her to him. " You weren't afraid to bear them—we were children yesterday. We are anxious, but we are not afraid. Really." Mrs. Cabal nods acknowledgment, but cannot talk because she would cry. Cabal : " Courage, my dear." Whispering to himself : "And may that little heart have courage." A series of flashes show Everytown in a belated wintry dawn. Men come from their houses carrying parcels or suitcases and go towards the station. A young wife saying good-bye to her husband, who is waiting for a tram. Bus stop. Men get on the bus with their packages. A sort of forced cheerfulness.

Air Attack

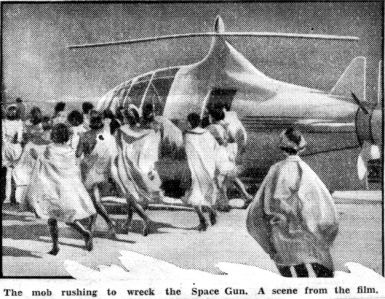

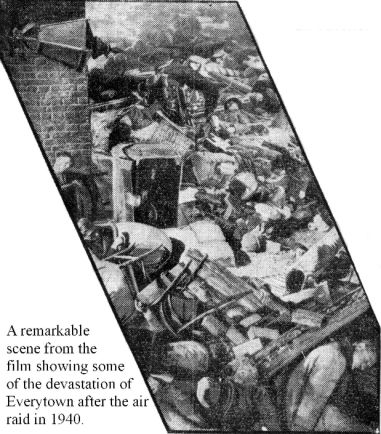

EVERYWHERE there are signs of war preparation. In the foreground a smooth-flowing river, or lake, that reflects the scene—suddenly the mirror is broken as enormous amphibian tanks crawl up out of the water. A gigantic howitzer suddenly rears itself up from a peaceful field. Roadways choked with war material moving up to the front. Long lines of tanks and caterpillar lorries. Long lines of steel-helmeted men. Lorries full of men. Lorries full of shells. Great dumps of shells. A fantasia of war material in motion. In a chemical factory piles of cases are being loaded. Gas bombs are being manufactured. The workers all wear gas masks of ghoulish type. Guns go off and there is a repetition of some of the foregoing scenes—but now the men and guns are no longer moving into action, but are in action. Guns being fired, tanks advance firing, battleships firing a broadside, gas hissing out of cylinders. A gun crew round a gun, passing shells up to the gun. Beneath an aeroplane a crew fixing bombs. Squadron after squadron of aeroplanes take to the sky. Everytown is seen with hostile aeroplanes in the sky. An explosion in the foreground fills the scene. As the smoke clears it reveals the suburban road in Everytown in which Passworthy lives, and something small and dark is seen far down the footpath. We pass up the road and before the shattered garden fence we see little Horrie Passworthy's son sprawling, dead. A long, silent pause. Scenes of Everytown being bombed. Sirens, whistles, and hooters. Panic working up in Square. Quick flashes of military working anti-aircraft guns. Again to crowded Square, terrified faces looking up. Increased panic. Aeroplanes overhead. A tramcar runs down the street, it lurches and falls sideways across the street. The facade of a gigantic general store falls into the street. The merchandise is scattered and on fire. Window dummies and wounded civilians lie on the pavement. Bomb bursting in crowded Square. Cinema crashing in ruins.

A bomb bursts a gas main, a jet of flame, the fire spreads. Officials distributing gas masks, the crowd in a panic. Fight for masks. Official swept off his feet. Aeroplanes distribute gas like a smoke screen. The cloud slowly descends on the town. The gas cloud descends, the guns continue to fire in the darkness. People in offices and flats trapped by the gas pouring into the windows. The Square is now very misty and dark. No civilians are moving about, but there are a few scattered dead.

IN the air an enemy airman, a boy of 19, is distributing gas. He finishes his supply and banks to turn about. He looks into the sky and discovers he is being attacked and is plainly apprehensive. His attacker is John Cabal. Cabal's aeroplane is bearing for the enemy. A fight ensues. It is a one-sided fight between a bomber and a swift fighter. Enemy airman crashes. Cabal nose-dives, but straightens out. Enemy airman crashing. Houses, etc., in the background under the cloud of gas he has spread. Cabal landing with difficulty. He looks towards enemy aeroplane and then hurries towards it. Fire breaks out in the wrecked machine as Cabal approaches it. Cabal arrives at enemy aeroplane. Enemy airman staggers out as the flames spread. He is beating out the fire in his smouldering clothing. He staggers and falls. Cabal helps the enemy airman, who is evidently very badly injured. He is as yet too stunned to be in anguish, but he knows he is done for. Cabal settles him fairly comfortably on the ground. Cabal : " Is that better? My God—but you are smashed up, my boy." Cabal tries to make him comfortable. He desists and stares at the enemy airman with a sort of blank amazement. " Why should we two be murdering each other? How did we come to this? " The gas is drifting nearer to them. The enemy airman points to it. " Go, my friend ! This is my gas, and it is bad gas. Thank you." Cabal : " But how did we come to this? Why did we let them set us killing each other ? " The enemy airman says nothing, but his expression assents. Cabal and the airman take their gas masks. Cabal helps the enemy airman with his mask and adjusts it. There is some difficulty due to the airman's broken arm ; Cabal desists and has to try again. Enemy Airman : " Funny if I'm choked by my own poison." Cabal : " That's all right." Cabal puts the mask on and then puts his own on. They hear a cry and look up. They see a little girl running before the gas. She is already choking and presses a handkerchief to her mouth. The girl, very distressed, runs towards them and hesitates, not knowing which way to go. She is heedless of the two men. Enemy airman stares, then tears off his mask and holds it out to Cabal. " Here—put it on her." Cabal hesitates, looks from one to the other. Enemy Airman : " I've given it to others—why shouldn't I have a whiff myself?" Cabal puts the mask on the girl, who resists, frightened, and then understands and submits. Cabal : " Come on, kiddy, this is no place for you. You make tracks that way. I'll show you." Cabal goes off with the girl and then returns to see if the enemy airman has a pistol. He realises that he has not, hesitates, and gives his own pistol to him. " You may want this." Enemy Airman : " Good fellow—but I'll take my dose."

THE enemy airman is dying in the flickering light of his burning aeroplane. The gas is very near now. The wisps drift towards him. He looks after Cabal and the girl. " I dropped the stuff on her. Maybe I've killed her father and mother. Maybe I've killed all her family. And then I give up my mask to save her. That's funny. Oh! that's really funny. Ha, ha, ha. That—that's a joke !" The gas drifts by him and he starts to cough. He remembers Cabal's words. " What fools we airmen have been ! We've let them make us fight for them like dogs. Smashed trying to kill her—and then I gave her my mask ! Oh, God ! It's funny. Ha, ha, ha." His laugh changes to a cough of distress as the gas envelops and hides him. The cough grows fainter and fainter, and vapour blots out the scene. " I'll take it all—take it all. I deserve it." He is heard again coughing and panting. Then comes a sharp cry, then a groan of sudden unendurable suffering. A pistol shot is heard. Silence.

THE war goes on. The newspapers report its progress. The Evening Newsletter, price threepence, declares on May 20, 1941 : " PROHIBITION OF SPECULATION," " THE END IN SIGHT," and " THE RATIONING SCANDAL." " The immense efforts and sacrifices of the Air Force during the great counter-offensive of last month," states the Newsletter, " are bearing fruit." Then there is seen a very roughly printed newspaper. It is printed from worn-out type and the lower lines fall away : THE WEEKLY PATRIOT No. 1. New Series. February 2, 1952. Price One Pound Sterling. DRAWING TO THE END " It is necessary to press on with the war with the utmost determination. Only by doing so can we hope. . . ." A third paper : THE WEEKLY PATRIOT No. 157. March, 1955. Price One Pound Sterling. THE UTMOST RESOLUTION. NO SURRENDER A desolate heath. Something burning far away. A sheet of decaying newspaper is fluttering in the wind. It catches on a thorn and, as the wind tears at it, there is time to read the ill-printed sheet of coarse paper : BRITONS BULLETIN September 21, 1966. Price Four Pounds Sterling. " Hold on. Victory is coming. The enemy is near the breaking point. . . ." The wind tears the scrap of paper to pieces.

Wandering Sickness

THERE are scenes of desolation everywhere. The Tower Bridge of London is in ruins. There are no signs of human life. Seagulls and crows. The Thames. partly blocked with debris, has overflowed its damaged banks. The Eiffel Tower prostrate. The same desolation and ruin. Brooklyn Bridge destroyed. The tangle of cables in the water. Shipping sunk in the harbour. New York, ruined, in the background. A sunken liner at the bottom of the sea. A pleasure sea front, Palm Beach or the Lido, Blackpool or Coney Island, in complete and final ruin. A few wild dogs wander through the desolation. Oxford University in ruins and the Bodleian Library scattered amidst the wreckage. The Central Square in Everytown. It is in ruins. A few ragged street vendors and a primitive market in a corner of the Square. A gigantic shell-thole is in the middle of the Square. A group of people stand about a board on the wall. This is a notice-board like the old Album on which news was written in the Roman Forum. As the world relapses old methods reappear. Notice on the board reads: NATIONAL BULLETIN August 1968 WARNING! A NEW OUTRAGE! ENEMY SPREADING DISEASE BY AEROPLANE, " Our enemies, defeated on land and sea and in the air, have nevertheless retained a few aeroplanes which are difficult to locate and destroy. These they are using to spread disease, a new fever of mind and body . . . " A man in a worn and patched uniform comes out of the Town Hall with a paper in his hand and turns towards the wall. He pastes up a new cyclo-styled inscription. The inscription, which runs a little askew, reads: "The enemy are spreading the Wandering Sickness by aeroplane. Avoid sites where bombs have fallen. Do not drink stagnant water." A woman comes out of a house. She is ragged and tired, a pail in her hand. She goes to the gigantic shell-hole in the middle of the square. The woman descends with her pail. She wants some of the water. A man comes into the picture. Man: " Didn't you read the warning?" The woman answers with a tired mute " No." Man, indicating the water : " Wandering Sickness." The woman is struck by instant fear. Then she hesitates. " I have to go half an hour away for spring water." The man shrugs his shoulders and goes. The woman is still hesitating. Near by is the hospital. It is a dim, dark place. The sick are unattended. One of them—a man in a dirty shirt and trousers—barefooted and haggard —rises, looks about hint wildly and darts out. He wanders into the Square outside. He stares blankly in front of him. He seeks he knows not what. People in the Square see hlm and scatter. The woman in the shell-hole discovers the wandering sick man is approaching her. She screams and scrambles away. A group of men and women run away from the sick man. A sentry with a rifle. A group of men and women enter the picture. Man (to sentry): " Don't you see?" Woman : " He is carrying infection." The sentry does not like his job, but! he lifts his rifle. He fires. The wandering man collapses, writhes and lies still. The sentry shouts: " Don't go near him. Leave him there !"

Back to Dark Ages

IN Dr. Harding's laboratory, the doctor is at his work bench, assisted by his daughter, Mary. He is struggling desperately to work out the problem of immunity to the Wandering Sickness which is destroying mankind. He is now a man of 50; he is overworked, jaded, aged. He is working in a partly-wrecked laboratory, with insufficient supplies. Harding's clothing is ragged and patched. His apparatus is more like an old alchemist's; it is makeshift and very inefficient. Harding mutters as he works. Mary is a girl of 18, dressed in a patched nurse's uniform, with a Red Cross armlet. " Father," she says, " why don't you sleep a little?" Harding: " How can I sleep when my work may be the saving of countless lives? —countless lives!" A shot is heard without. Harding goes to the window, followed by Mary. He sees the man with the Wandering Sickness lying dead, and remarks: "And so our sanitation goes hack to the cordon and killing! This is how they dealt with pestilence in the Dark Ages." Harding examines some preparation, and, without looking back, says: " Iodine, please." Mary takes a step towards him. A glass or container in her hand. She looks at it and tilts it to ascertain its contents. She is unable to speak because she knows the portent of her answer. Harding : " Mary ! —iodine, please." Mary : " There is no more, father. There is just one drop." Harding turns back as if stabbed. " No more iodine?" Mary replies with a shake of her head. Harding almost collapses and sits down. " My God!" He buries his head in his hands. His voice almost a sob: " What is the good of trying to save a mad world from its punishment?" Mary : " Oh, father, if you could only sleep for a time." Harding: " How can I sleep ? See how they wander out to die." He rises and looks at his daughter, deeply moved. " And to think that I brought you into this world." Mary : " Even now I am glad to be alive, father." Harding pats her shoulder. A quick affectionate gesture. Then he walks up and down in deep mental distress. " This is the last torment of this endless warfare. To know what life can do and be—and to be helpless." He takes the slip from under the microscope eyepiece and dashes it to the floor in impotent rage. He sits down in utter despair. A step on the staircase outside. They both look towards the door Mary : " Richard !" Richard Gordon. a former air mechanic, enters. Harding stares at him, fearing his news. Gordon : " My sister . . . " Harding : " How—do you—know ?" Gordon : " Her heart beats fast. She feels faint. And — and — she won't answer." Harding says nothing. Gordon : " What can I do for her ?" Harding, pained, silent and beaten. Gordon : "I thought — something —might be known." Harding does not move. Mary cries : " Oh, Janet !—and you, poor dear—" She approaches Gordon and Gordon makes a movement as if to warn her that he may, too, be infected. She does not care. " Richard," she whispers, close to his face. Harding rises and goes without a word. It is the doctor's instinct to try and help where everything seems hopeless.

Deserted Suburbia

IN Gordon's living room Janet, his sister, turns to and fro on her bed. Enter Harding, followed by Richard and Mary. Harding approaches the bed. He pulls back the sheets, listens to Janet's breathing. Then he replaces the sheets and shakes his head. He rises from the bed. Gordon asks a mute question. Harding: " No doubt of it. And it need not be. Oh, to think of it! There is just one point still obscure. But I cannot even get iodine now—not even iodine ! There is no more trade, nothing to be got. The war goes on. This pestilence goes on—unchallenged—worse than the wars that released it." Gordon : " Is there nothing to make her comfortable?" Harding : " Nothing. There is nothing to make anyone comfortable any more. War is the art of spreading wretchedness and misery. I remember when I was still a medical student talking to a man named Cabal about preventing war. And about the researches I would make and the ills I would cure. My God ! " Janet rises from the bed. Her face is now ghastly white and her eyes are glassy. She comes towards Gordon and Mary. The two stare at her, horror-stricken, as she passes them. Her face advances to a close-up. She leaves the room. After a second's hesitation Gordon rises and hurries after his sister. Mary takes a few steps and then sits down. Janet wanders in the Square. Gordon reaches her and tries to take her arm, but she shakes him off. They go towards the crowd about the noticeboard in front of the Town Hall. The crowd disperses, panic-stricken. Janet and Gordon walking towards the sentry. The sentry lifts his rifle. Gordon protects Janet with his body. To sentry : " No! Don't shoot; I will take her out of the town." Sentry hesitates. Janet wanders off. Gordon hesitates between the sentry and her and then follows her. Sentry turns after them, still irresolute. Janet and Gordon wander through the ruins of Everytown. She goes on ahead feverishly, aimlessly. He follows her. We are thus given a tour through Everytown in the uttermost phase of collapse. A dead city. Rats flee before them—starveling dogs. They pass across a deserted railway station. Public gardens in extreme neglect. Smashed notice-boards. Fountains destroyed—railings broken down. Suburban road with villas empty and ruinous. In the gardens are bramble-thickets and nettle-beds. Janet and Gordon pass the former house of Passworthy, recognisable by the shattered fence. Janet drops and lies still. Gordon kneels down beside her. At first he cannot believe she is dead. He picks her up in his arms and carries her off. He is seen far away carrying her into a mortuary. Hooded figures come out to take her from him—all very far away. Mary waits in Gordon's room. It is now twilight and her face is very sad and still and pale. She looks towards the door when at last Gordon comes staggering in. He is the picture of misery. " Oh Mary, dear Mary," he cries. Mary holds out her arms to him. He clings to her like a child.

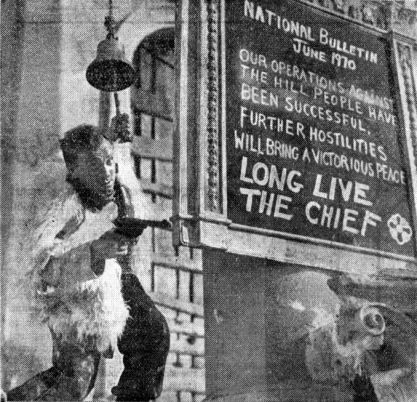

It is 1970—three years later. The Square of Everytown has recovered a little from the extreme tragic desolation of the pestilence stage. Clumsy efforts to repair ruined buildings have been made. No shops have been reopened and half the houses are unoccupied, but the shellhole in the centre has been filled up. There is a sort of market going on with patched and ragged people haggling for vegetables and bits of meat. Few people have boots. Most people are wearing footwear of bast and rags or sabots of wood. Few hats are worn and those old. The women are bare-headed or have shawls over their heads. The vehicles are not rude and primitive, but old broken-down stuff. One or two boxed things with old carriage wheels or motor-car wheels—which people push. Few or no horses. A cow or a goat being milked. There is a peasant with a motor-car (small runabout without tyres) with a lot of carrots and turnips in it, drawn by a horse. The camera moves round to give a general view of the Square, coming to rest outside the Town Hall. A big resette flag hangs over the portico of the Town Hall. This rosette is the symbol of the ruling Boss and his government. A small group watching a rosetted guard writing with charcoal on the wall ! At the top he has drawn and smeared a rough rosette:

NATIONAL BULLETIN Mayday A.D. 1970 The Pestilence has Ceased. Thanks to the determined action of our Chief in shooting all wanderers. There have been no cases for two months. The Pestilence has been conquered. The Chief is Preparing to Resume Hostilities Against the Hill People with the Utmost Vigour. Soon we shall have Victory and Peace. All is well—God save the Chief. God save our Land.

Inside a near-by aeroplane hangar, Gordon, three years older, and in a different, rather less dishevelled costume, is working on an aeroplane engine on the bench. Behind him is the dismantled aeroplane. Two assistants with him. He examines the high-tension wires. Gordon: " This rubber is perished. Have we any more insulated wire?" First Assistant: " We've got no rubbered wire at all, sir." Gordon : "Any rubber-tape?" Second Assistant: " Not a scrap of rubber in the place. We used the last on the other motor." Gordon slowly rises, defeated : " Oh what's the use—there's no petrol anyway. I don't believe there's three gallons of petrol left in this accursed ruin of a town. What's the good of setting me at a job like this? Nothing will ever fly again. Flying is over. Everything is over. Civilisation is dead."

Lost Skill

LATER, Gordon and his wife, Mary, meet the Boss with his retinue in the Square. They are a semi-military brigand crew with little that is uniform about them except the prevalent rosette badges. The Boss is a big swaggering fellow with a hat cocked an one side hearing a rosette in front of it. His frogged tunic might have belonged to a Guards bandsman. He has a sword, a dirk and two pistols. Neat riding breeches and boots. A scarf tied across his breast bears the rosette symbol. His manners might be described as the decaying civilities of a London taxi-cab driver. Boss : " Anything to report, Gordon?" Gordon : " Nothing very hopeful, Chief." Boss : " We must have those planes— somehow." Gordon: " I'll do what I can, but you can't fly without petrol." Boss : " I'll get petrol for you, trust me. You see to the engines. I know you haven't got stuff—but surely you can get round that. For example, transfer parts. Have you tried that? Use bits of one to mend the other. Be resourceful. Give me only ten in working order. Give me only five. I don't want them all. I'll see to it you get your reward. Then we can end this war of ours—for good. This your wife, Gordon? You've kept her hidden. Salutation, lady! You must use your influence with our Master Mechanic, lady. The combatant State needs his work." Mary doesn't like the situation. " I'm sure my husband does his best for you, Chief." Boss: " His best! That isn't enough, lady. The combatant State demands miracles." Roxana, a consciously beautiful woman of 28, comes upon the scene. She and the Ross speak familiarly. The Ross complains to her. " What do you think of our Master Mechanic here—Who won't give me planes to finish up that little war of ours with the hill people?" Roxana surveys Gordon with her arms akimbo, and then considers Mary and the Boss more deliberately. She rather likes the look of Gordon. She perceives that the Boss has been showing off at Mary and she wants to take him down a little. She speaks with a faint shrewish mockery to the Boss. " Can't you make him? I thought you could make everybody do everything." Gordon : " Some things can't be done, Madam. You can't fly without petrol. You can't mend machines without tools or material. We've gone back too far. Flying is a lost skill in Everytown."

The 1970 Plane

SUDDENLY the throbbing of an aeroplane very far away becomes faintly audible. Gordon's face changes as the beating of the aeroplane dawns on his consciousness. He is puzzled. He looks up in the sky. He points silently. It is a small new 1970 aeroplane, with wings that curve like a swallow. There is general excitement. The eyes of the crowd follow the plane and indicate it is circling down to a descent. The Boss is the first to become active. " What's all this? Have they got aeroplanes before us? And you tell me we can't fly any more ! While we have been—fumbling, they have been active. Here, some of you, find out who this is and what it means! You (to one of his guards), you go, and you (to another). There was only one man in it. Hold him."

THE Boss, who is the centre of activity, commands his men to bring the airman to him. The excited people meanwhile watch the airman alight from his machine. He is John Cabal, who is now grey-haired with a lined face. He is dressed in shiny black and wears a sort of circular shield over head and body that makes him over 7ft. high. It is like a round helmet enclosing body as well as head. It is a 1970 gas-mask. The visor in front swings down, so that his head and shoulders seen from in front are suggestive of a Buddha against a circular halo. The black mask behind his head and shoulders is ribbed like a scallop-shell. Cabal refuses to obey the command of the Boss to see him in the Town Hall, but instead goes with Harding, Gordon and Mary to the doctor's laboratory, where he learns about the Boss and his control of Everytown. In the Town Hall the Boss has staged things for the reception of the strange airman. He sits at a vast desk. A few guards, secretaries and yes-men around him. Simon Burton, his right-hand man, sits at a side table. Roxana watches proceedings—comes and stands close beside the Boss at his right hand. Whispers to him. She displays the excitement of a woman before a bull-fight. A lively contest is going to happen and she has an impression that the strange visitant may prove an interesting novelty. Things have been dull in Everytown lately. The atmosphere is strained. The scene is set and the principal actor does not enter. The Boss is impatient to see Cabal and Cabal does not come. Messengers are sent and return. Boss: " Where is this man? Why isn't he brought here?" Everyone looks uneasy. The Boss turns to Burton. Burton: " He has gone off with Dr. Harding." The Boss rises. " He has to he brought here. I must deal with him." Guards are dispatched to bring Cabal.

In Harding's laboratory the group are still talking. Cabal : " So that's the sort of man your Boss is. Not an unusual type. Everywhere, you see, we find these little semi-military upstarts robbing, fighting. That is what endless warfare has worked out to—brigandage. What else could happen? And we, who are all that is left of the old engineers and mechanics, are turning our hands to salvage the world. We have the airways, what is left of them; we have the sea. We have ideas in common; the freemasonry of efficiency—the brotherhood of science. We are the natural trustees of civilisation when everything else has failed." Gordon: " Oh, I have been waiting for this. I am yours to command." Cabal : " Not mine. Not mine. No more bosses. Civilisation's to command. Give yourself to World Communications." A knock at the door. They turn. The oafish guard comes into the room. Three others who have been sent for him by the Boss are behind. One of them says: "Tell him he's got to come. If he won't come on his feet, we'll carry him." The First Guard: "Lord knows what will happen to me, sir, if you do not come." Cabal shrugs his shoulders, rises, reflects, hands his great gas-mask to Gordon and stalks out, the guards following respectfully. The gas-mask is not in evidence in the next scene.

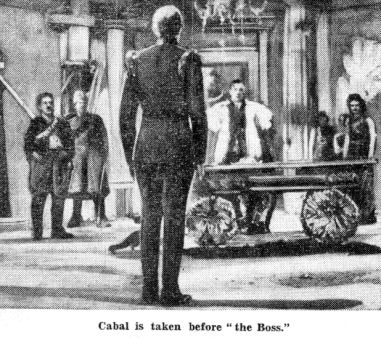

Before "The Boss"

IN the Town Hall. The Boss at his great desk. Roxana very alert behind him. Simon Burton at his own table. As the guard and Cabal approach, the Boss draws himself up in his chair, and attempts a lordly pose. Cabal's bearing is easy and familiar. The Boss is sturdy and ornate. Cabal tall, lean, black and dry. Cabal : " Well, what do you want to talk to me about?" Boss : " Who are you? Don't you know this country is at war?" Cabal : " Dear, dear ! Still at it. We must clean that up." Boss : " What do you mean? We must clean that up? War is war. Who are you, I say?" Cabal pauses before he replies. "The law," he says. He improves it : " Law and sanity." Roxana watches him. Then looks to the Boss. Boss, a little late: " I am the law here." Cabal : " I said law and sanity." Boss : " Where do you come from? What are you? " Cabal : " Pax Mundi. Wings over the world." Boss : " Well, you know, you can't come into a country at war in this fashion." Cabal : "I'm, here. Do you mind if I sit down?" He sits down and leans across the table, looking intelligently and familiarly into the face of the Boss. " Well?" he says. Boss: " And now for the fourth time, who are you?" Cabal: " I tell you, Wings—Wings over the World." Boss: " That's nothing. What Government are you under?" Cabal : " Common sense. Call us Airmen if you like. We just run ourselves." Boss: " You'll run into trouble if you land here in war-time. What's the game?" Cabal: " Order and trade—" Boss: " Trade, eh? Can you do anything in munitions?" Cabal: " Not our line of business." Boss: " Petrol—spare parts? We've got planes—we've got planes—we've got boys who've trained a bit on the ground. But we've got no fuel. It hampers us. We might do a deal." Cabal reflects and looks at his toes: " We might." Boss: " I know where I can get some fuel. Later. I've got my plans. But if you could manage a temporary accommodation—we'd do business." Cabal: " Airmen help no one to make war." Boss, impatiently: " End war, I said. End war. We want to make a victorious peace." Cabal: " I seem to have heard that phrase before. When I was a young man. But it made no end to war." Boss : " Now look here, Mr. Aviator. Let's be clear how things are. Come down to actuality. The way you swagger there, you don't seem to understand you are under arrest. You and your machine." Mutual mute interrogation. Cabal: " You'll get other machines looking for me—if I happen to be delayed." Boss: " We'll deal with them later. You can start a trading agency here if you like. I've no objection. And the first thing we shall want will be to have our own aeroplanes in the air again." Cabal: " Yes. An excellent ambition. But our new order has an objection to private aeroplanes." Roxana, softly for Boss to hear: " The impudence!" Boss half glances at her with a faint anxiety. " I am not talking of private aeroplanes. The aeroplanes we have here are the public aeroplanes of our combatant State. This is a free and sovereign State. At war. I don't know anything about any new order. I am the chief here, and I am not going to take any orders—old or new—from you." Roxana asks: " Where do you come from? " Cabal smiles and replies: " I flew from our headquarters at Basra yesterday. I spent the night at an old aerodrome at Marseilles. We are gradually restoring order and trade all over the Mediterranean. We have some hundreds of aeroplanes and we are making more, fast. We have factories at work again. I'm just scouting a bit to see how things are here." Boss : " And you've found out. We've got order here, the old order, and we don't want anybody else restoring it, thank you. This is an independent combatant State." Cabal: " We've got to talk about that." Boss : " We don't discuss it." Cabal: " We don't approve of these independent combatant States." Boss : " You don't approve !" Cabal: " We mean to stop them." Boss: " That's—war." Cabal: " As you will. My people know I'm prospecting. When they find I don't come back they'll send a force to look for me." Boss, grimly: " Perhaps they won't find you." Cabal shrugs his shoulders. " They'll find you." Boss: " They'll find me ready. Well, I think we know now where we stand. You four guards take this man, and if he gives any trouble club him. Club him. You hear that, Mr. Wings over your Wits? See to it, Burton. Have him taken to the detention room downstairs." He stands up as if dismissing the assembly.

A Captive

THE scene changes to a small bare room like the waiting-room of a police station. It is poorly lit by a barred window. Cabal sits on a wooden chair with his arms on a bare table and contemplates the situation. Cabal: " I've tumbled into a hole. It's the old old story of the over-confident wise man and the truculent rough. . . . It may be weeks before I'm reported as missing. They'll think my radio has broken down. Meanwhile Mr. Boss here does as he likes. . . ." " Escape?" He contemplates the room. Stands up and stares at the window bars. "They'll have my machine guarded. . . ." Sits down again, laughs bitterly at himself and drums with his fingers on the table. Then he jumps up impatiently. Goes to the window. Close-up of his face in the dim light. " I suppose everyone must do something hopelessly foolish at times. I've walked into it. I—the planner of a new world. . . . " Just at this time with everything ready. . . . " If this mad War dog here bites me —and I die—I wonder who will carry on. . . . " No man is indispensable . . ." He tries the firmness of the bars in the window. Fade-out upon his hands holding the bars.

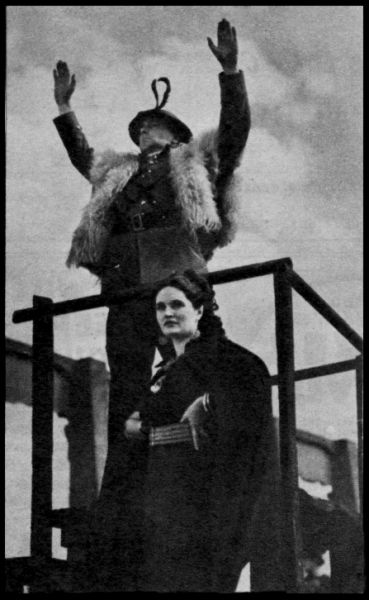

SCENE outside the Town Hall. A small troop of mounted men with a flag leaving for the war. Two led horses are brought up and the Boss and Roxana appear and mount. The whole body rides off. A small not very enthusiastic crowd. watches their departure. There is a feeble cheer as the detachment goes off. Fight on a hill overlooking some coal pits. The Boss directs operations. With him are his irregular troop leaders. They gallop off, The Boss's cavalry attack some rough trenches. The defenders are overwhelmed and seen running away. The Boss's men are victorious, the enemy routed. The Central Square. A troop of mounted men ride into the Square. Following come the Boss and Roxana triumphant. Flags decorate the side streets. The crowd shows a new enthusiasm. People cheer as the Boss and Roxana pull up outside the Town Hall. Man watching: " We have captured the coal pits, and the old oil retorts, and we have got oil at last." Later, Boss addresses eight or nine officers in the Town Hall. Gordon is seen under arrest. Burton and Roxana look on. Boss : " Victory approaches. Your sacrifices have not been in vain. Our long struggle with the Hill Men has come to its climax. Our victory at the old coal pits has brought a new supply of oil within reach. Once more we can hope to take the air and look invaders in the face. We have nearly 40 aeroplanes, as big a force, I venture to say, as any in the world now. This oil we have got can be adapted to our engines. That is quite a simple business. " Nothing remains to be done but a conclusive bombing of the hills. Then for a time we shall enjoy a rich and rewarding peace, the peace of the strong man armed who keepeth his house. And now at this supreme crisis you, Gordon, our master engineer, must needs refuse to help us. Where are my planes ? " Gordon: " The job is more difficult than you think. Half your machines are hopelessly old. You haven't got 20 sound ones. To be exact, 19. You'll never get the others off the ground. The thing cannot be done as you imagine it. I want assistance." Boss: " What assistance? " Gordon : " Your prisoner." Boss turns to him. " You want that fellow in black—Wings over the World? You want him released?" Gordon: " He knows his business. I don't enough. Make him my—technical adviser." Boss: " I don't trust you technical fellows." Gordon: " Then you won't get an aeroplane up." Boss : " I want those planes." Gordon shrugs his shoulders. The Boss meditates, walking to and fro. Boss: " And if you get him?" Gordon: " Then I want Dr. Harding out, too." Boss: " They're—old associates." Gordon : " I can't help that. If anybody in Everytown can adapt that crude oil for our aeroplanes it is Harding. If not, it can't be done." Boss: " We've had a bit of an argument with Harding." Gordon: " He's the only man who can do this work for you." Boss: " Bring in Harding."

HARDING is brought in. He is dishevelled, and his hands are tied. He looks as if he has been manhandled. Boss: " Untie his hands." The guard releases Harding. The Boss pauses and looks at Harding " Well?" Harding: " Well, what?' Boss: " The salute." Harding: " Damn the salute." The guard steps forward. Boss : " Never mind the salute now. We'll talk about that afterwards. Now let us see where we are. You, Gordon, are to direct the reconstruction of our air forces. The prisoner Cabal is to be put at your disposal. Everywhere he goes he is to be under guard and observation. No relaxing on that. And neither he nor you must go within fifty yards of his plane. Mind that! You, Harding, are to help Gordon with this fuel problem and to put your knowledge of poison gas at our disposal." Harding: " I tell you, I will do nothing with poison gas." Boss : " You've got the knowledge—if I have to wring it out of you. The Combatant State is your father and your mother, your only protector, the totality of your interests. No discipline can be stern enough for the man who denies that by word or deed." Harding : " Nonsense. We have our duty to civilisation. You and your like are heading back to eternal barbarism." The entourage is dumbfounded. Burton starts forward. " But this is pure treason." Harding: " In the name of civilisation, I protest against being dragged from my work. Confound your silly wars! Your war material and all the rest of it! All my life has been interrupted and wasted and spoilt by war. I will stand it no more." Burton " This is Treason—Treason." Guards rush upon Harding, seize him and twist his arms. Harding snarls with pain. Roxana comes forward. Roxana: " No. Stop that." The guards stop. Harding is sullen and silent. Boss comes very close to him. Boss: " We have need of your services." Harding: " Well, what do you want?" Boss: " You are conscripted. You are under my orders now and under no others in the world. I am the master here! I am the State. I want fuel—and gas." Harding: " Neither fuel nor gas." Boss: " You refuse?" Harding: " Absolutely." Boss: " I do not want to be forced to extremities." Roxana, who had come in during the conversation, whispers to the Boss, with her eyes on Gordon. Gordon comes fully into the picture. He has a scheme of his own. He looks hard at Roxana as though he was silently trying to will her aid. The confidence in his manner, the faint streak of impudence in his nature, increases. Gordon : " Sir—may I have a word? I understand you want all of these out-of-date crocks of yours, which you call your air force, to fly again—and fly well?" Boss: " They shall." Gordon: " With the help of that man—Cabal—you have in the cells here, and with the help of Doctor Harding here—you may even get a dozen of your planes in the air again." Harding: " You are a traitor to civilisation. I won't touch it." Gordon ignores him: "If you will give me Cabal and—if you will leave me free to talk with the Doctor, I promise you will see your air force—a third of it at any rate—in the sky, again." Boss: " You talk as though you were driving a bargain with me." Gordon : " I am sorry, Chief. It is not I who make these conditions. It is in the nature of things. You cannot have technical services, you cannot have scientific help unless you treat the men who give it you—properly." Roxana to the Boss, but quite loud: " That's what I have said all along! You are bullying too much, my dear. There is a limit to bullying. Why! You can't make a dog hunt by beating it." Boss : " I want those aeroplanes." Gordon : " Well." Boss : " And I mean to be master here." Roxana : " Then you have to be reasonable, my dear, and that's all about it."

THE scene changes and Gordon and Cabal are seen at work upon that aeroplane engine which previously puzzled Gordon. The two men quite understand each other. Cabal works and Gordon learns from him. The four guards watch and poke their noses about and listen conscientiously but perplexedly. They glance at one, another. They are much too oafish to control the conversation. Cabal, between his teeth: " If only they'd let us go back to my own plane. There's a radio there." Gordon: " Hopeless. . . . Won't even trust me." Cabal: " We'll have to make a job of this." Gordon : " I could send men for your reserve petrol. They'll give me that. For this." Cabal : " Good." Then louder as if explaining the machine. "One of the most difficult bits in this is what is called the get-a-way—it's a sort of cut out. But I have some ideas." Gordon : " We'll manage it, I think. Now that Dr. Harding understands his part of the job . . ." They nod reassuringly to each other, and then glance at the stupid faces of their guards. It's safe.

EVENING. Cabal is sitting in his cell lit by the light of two candles. He looks bored and despondent. He turns round at a knocking at his door. " Come in. Don't stand on ceremony." The door is opened deferentially by a guard. Roxana appears, rather specially dressed. Cabal has not expected anything of this sort. He is a man of experience with women, although he has none of the Boss's devouring enterprise. He stands up. She walks in, carrying herself with a certain consciousness of her effect. He bows and remains silent. ROXANA : "I wanted to look at you." CABAL, stiffly: "At your service, Madam." ROXANA : "You are the most interesting thing that has happened in Everytown for years." CABAL: "You honour me." ROXANA : "You come from—outside. I had begun to forget there was anything outside. I want to hear about it." CABAL : "May I offer you my only chair? " There follows a long conversation in which Roxana endeavours to persuade Cabal to tell her everything about the outside world. For his confidences she promises to help him out of his difficulty. Suddenly they are interrupted. The Boss enters.

"The Boss" Warned

Boss: "So this is where you are!" ROXANA : "I said I should talk to him and I have." Boss: "I told you to leave him alone." ROXANA : "Yes, and sat up there drinking and looking as wonderful and powerful as you could. Rudolf the Victorious! I know—you sent twice to ask Gordon and his wife to come! So that she should see you in your glory. And here am I trying to find out for you what this black invader means. Do you think I wanted to come and talk, to him "—she turns to Cabal—" this grey cold man? While you are swaggering here, more aeroplanes are getting ready away there at Basra." Boss: "Basra?" ROXANA : "His headquarters. Have you never heard of Basra?" Boss: "These are matters for men to talk about." CABAL: "Your lady has been putting me through a severe cross-examination. But the gist is—that away there in Basra the aeroplanes are rising night and day like hornets about a hornets' nest. What happens to me here is a small affair. They'll get you. The new world of the united airmen will get you. Why, listen! You can almost hear them coming now." Roxana leaves the room. When she has gone out the Boss turns and comes towards Cabal. Boss: "I don't know what she has been saying to you. Perhaps I don't care. Not as much as she thinks. There's no following her chopping and changing. I've had about enough of it. But I'm not a fool. There's no making peace between you and me. None at all. It's your world or mine. It's going to be mine—or I die fighting. After all this threatening—swarms of hornets and so on—you are a hostage. Understand. No one comes near you. Your friend Gordon will have to manage without you. And don't be so sure you'll win. So just go on sitting here and thinking about it, Mr. Wings over the World."

THE following day, bright daylight shining into the laboratory of Dr. Harding. Mary leans against the work bench and Roxana is talking to her. ROXANA : "It is not only that I want to protect you from the insults of the Chief. Oh! I know him. But I want to talk to you about this man Cabal and this Airmen's World they talk about. What is this new world that is coming? Is it a new world really or it only the old world dressed up in a new way? Do you understand Cabal? Is he flesh and blood?" MARY : "He's a great man. My father knew him years ago. My husband worships him." ROXANA : "He's so cold—so preoccupied. And so—interesting. Do men like that ever make love? " MARY : "A different It ort of love, perhaps." ROXANA : "Love on ice. If this new world—all airships and science and order—comes about, what will happen to us women?" MARY: "We shall work like the men." ROXANA : "You mean that? Are you —flesh and blood?" MARY: "As much as my husband and father." ROXANA (with infinite contempt) : "Men !" Sometimes—when I think of lean grim Cabal—I believe this world of yours must come. And then I think —it can't come. It can't. It's a dream. It will seem to come, but it won't come. It's just a new lot of men at the top. There will be wars still. Struggles still." MARY : "No, it will be civilisation. It will be peace. This nightmare of a world we live in—that is the dream, that is what will pass away." ROXANA : "No. No. This is reality." MARY, staring in front of her: "Do you really think that war and struggle —mere chance gleams of happiness—general misery — all this squalid divided world about us, do you think it must go on for ever?" ROXANA : "You want an impossible world. Nice in a way—perhaps, but impossible. You are asking too much from men and women. They won't bother to bring it about. You are asking them to want unnatural things. What do we want? We women. Knowledge, civilisation, the good of mankind? Nonsense! Oh, nonsense. We want satisfaction. We want glory. I want the glory of being loved—the glory of being wanted—desired, splendidly desired—and the glory of feeling and looking splendid. Do you want anything different? No. But you haven't learned to look facts in the face yet. "I know men. Every man wants the same thing—glory! Glory in some form. The glory of being loved—don't I know it? The glory they love most of all. The glory of bossing things. here—the glory of war and victory. This brave new world of yours will never come. This wonderful world of reason! It wouldn't be worth having if it does come. It would be dull and safe and—oh, dreary! No lovers—no warriors—no dangers—no adventure." MARY: "No adventure! No glory in helping to make the world over—anew! It is you who are dreaming." The noise of an aeroplane is heard growing rapidly louder. They turn to the window and look out. They become excited. They crane up at an aeroplane circling overhead. It makes a great old-fashioned roar. ROXANA " Look ! It's your Gordon. he's flying at last."

Gordon's Escape

IN the aeroplane is Gordon at the controls. He is satisfied. Behind him sits a rosetted guard. Gordon turning the machine round. Everytown is far below. The machine flies on. The guard stirs. He protests inaudibly because of the roar of the engine. Gordon disregards him. Guard taps Gordon's shoulder, signs for him to return, and presently, finding no response but a cheerful smile, points his pistol. Mutual scrutiny. Guard weakly menacing. Gordon points over the side of the cockpit. He smiles suddenly, having taken the measure of his man, and puts his fingers to his nose. The aeroplane jerks sharply upwards, and the guard, no longer pointing his pistol, but gripping tight, is manifestly scared. Aeroplane looping the loop—then the falling leaf trick. Guard's ordeal through all this motion. He drops the pistol and grips the side. Pistol falling. Hitting the ground and exploding. The aeroplane seen flying away over the hills. " And so I got away," says Gordon's voice. As the voice is heard, the last scene dissolves into the next.

The New Power

CONFERENCE room at Basra, rather like an ultra-modern board room. It is bleakly and rationally furnished. Telephones have been restored to the world. Through a large open window one sees the great and growing aerodrome of Basra with a number of aeroplanes coming and going. Far off there is a group of smoking factory chimneys. It is a sudden contrast to the general ruinousness that has prevailed throughout this film since the war sequences. A dozen young and middle-aged men sit at the table indifferent to these familiar activities outside, and Gordon stands talking—too excited to sit. Gontdon : "And so I got away. That is where you will find Cabal. The Boss of Everytown is a violent tough—he may do anything. There is no time to lose." A MIDDLE-AGED MAN : " Certainly, there is no time to lose. Half squadron A is ready now. You ready to go with them, Mr.— ?" GORDON : " Gordon, sir." The middle-aged man begins to dial a telephone. A YOUNG MAN : " This gives us a chance of trying this new anaesthetic, the Gas of Peace . . . I wish I could go. . ."

THE Boss is next seen in his bedroom. He is in deshabille and has just got out of bed. With him is Burton and by the door stands a messenger. BURTON: " At last we have definite news." BOSS : " What is it?" An attendant brings in a tray of breakfast and sets it on the table. BURTON : "Gordon didn't fall into the sea. He got away. A fishing boat saw him making the French coast. Perhaps he reached his pals." Boss, disagreeably: " Well?" BURTON : "He'll be coming back. He'll be bringing the others with him." Attendant leaves. The Boss is waking up slowly and is very peevish : "Curse this Air League. Curse all airmen and gasmen and machinemen ! Why didn't we leave their machines and chemicals alone. I might have known. Why did I tamper with flying?" BURTON : " Well, we needed aeroplanes—against the Hill State. Somebody else would have started in again with aeroplanes and gas and bombs if we hadn't. These people would have come interfering anyhow." BOSS: "Why was all this science ever allowed? Why was it ever let begin?" He turns listlessly to his breakfast. He begins again: "Science!—it's the enemy of everything that is natural in life. I dreamt of those chaps in the night. Great ugly inhuman chaps in black. Half like machines. Bombing and bombing." BURTON: "I guess they'll come bombing, all right." BOSS: " Then we'll fight 'em. Since Gordon got away I've had one or two of the air boys to see me. Those boys have guts. They can do something still." He walks up and down devouring a piece of bread. " We'll fight 'em. We'll fight 'em. We've got hostages. . . . I'm glad now we haven't shot them anyhow. I wonder if that fellow Harding. . . . Of course ! He can tell us what to do about this gas. If we have to wring his arm off and knock half his teeth down his throat to make him do it. Get him—get him." Burton at door shouting for men and giving orders. The Boss is gathering courage and takes his food with greater gusto: "They have to come to earth sometime. What is this World Communications? A handful of men like ourselves. They're not magic." The scene changes. Outside the hangar there is a row of worn-out aeroplanes. A number of very young inexperienced-looking pilots stand before them. The Boss is inspecting them. Roxana is beside him. The Boss begins his speech : "To you I entrust these good, these tried and tested machines. You are not mechanics—you are warriors. You have been taught not to think, but to do—and—if need be, die. I salute you —I, your leader." The boy pilots go off rather reluctantly to their machines and start them up. It is an almost "Heath Robinson" scene of our contemporary (1935) machines in the last stage of decay and patch-up.

SUDDENLY there comes into view a new type of air bomber flying with a sort of remorselessness—in contrast with the hops and misbehaviour of the Boss's machines. It is Gordon returning. Two other big bombers follow, low down in the sky. The machine has a distinctive throb of its own. In closer shots of the great bomber there can be seen aviators (three men and two women) standing about looking down on the world. One is Gordon. Gordon is anxious. The Boss is with Burton and Roxana and his staff. The Boss studies the familiar skyline through binoculars. Guards bring in Mary and Harding. The Boss turns to them. BOSS : "What do you know about these Air League people? Have they gas? What sort of gas?" HARDING: " I know nothing of gas." BOSS: "Here, where are the masks?" Two boys appear with a job lot of masks—caricatures of existing types. BOSS : "Tell us about these masks, anyhow." Harding examines a mask and tears it and throws it down. "Rotten! No use at all." BOSS : "What gas have they got?" HARDING : " Gas war isn't my business." BOSS : "Well, they can't gas us when you are here, anyhow." BURTON, in dismay : " Here they are. Listen. They're coming already!" The strange recognisable throb of Gordon's aeroplanes is heard. The Boss rushes forward and looks up with his binoculars: "Clumsy great things! Our boys will have them down in five minutes. They're too clumsy. What!—Only six of us up. Where are the rest of our fellows?" Sudden consternation of the group at something unseen. A machine falls in flames and crashes in the distance. BOSS : "Go on—up at him." A loud report. Far off another aeroplane crashes in flames. ROXANA : " Poor boy—it's got him." BOSS : " They're both coming down. Cowards!" ROXANA : " But they can't use gas—how can they use gas?—when we have the hostages." The Boss turns and looks at the hostages. " Ah! The hostages! I'm not done yet. Lead them out—there. Tie 'em up. Out there in the open. Where they can be seen." GUARDS take Mary and Harding out to the open and tie them up to two posts. Closer shot of Mary and Harding being tied to the posts. They look at one another with steady eyes. Then they look up at the sky.

Gas Attack

The Boss comes over to them, brandishing his pistol. He shouts up to the sky : "Come down, or I shoot them. Are you bombing your own hostages? Come down or I shoot." He remembers Cabal. " Where's the other fellow ? He's the Prize Hostage. He's the best of all. They'll know him. Four of you—go and fetch him . . ." A deep soft thud and a bomb explodes some distance off. The sound the bomb makes is not a sharp explosive report ; it is more like the whoof of a puff of steam. A soldier cries out : "Is it gas ? " The BOSS waves his pistol at Mary and Harding. "You, anyhow, shall die before I do." Roxana stands near him. Another bomb thuds nearer. The Boss points his pistol at Harding with an expression of desperate resolution, but Roxana knocks it up as he fires. BOSS : " You turn against me?" ROXANA : " Don't you see—he's beaten you. Look !" Soldiers in the distance are seen staggering and falling. The gas this time is transparent, and is visible only as a sort of shimmering heat haze. The foreground now is still perfectly clear, but the middle distance is flickering. ROXANA rushes to Mary and clings to her : "Mary—I never did you any harm. I saved your father. I saved you. Couldn't you call up to your man —to stop this . . ." Crescendo of whoofs close at hand. Whoof. WHOOF. WHOOF. The gas increases and creeps nearer and nearer. The Boss looks with amazement at his men gradually succumbing to the gas. He starts and pulls himself together. BOSS : " Shoot them ! What are you all doing? Why don't you move? I won't have it like this. What's happening? Everything is going swiminy! 'Everything is swimming." He wipes his hand across his eyes as if he can no longer see or think distinctly. His face is suddenly distorted in a last violent effort to resist the gas. BOSS : "Shoot, I say! Shoot. Shoot. We've never shot enough yet. We never shot enough. We spared them. These intellectuals ! These contrivers. These experts! Now they've got us. Our world or theirs. What did a few hundreds of them matter? We've been weak—weak. Kill them like vermin ! Kill all of them ! . . . Why should I be beaten like this ? Weakness ! Weakness ! Weakness is fatal ! . . . Shoot ! "

A New Start

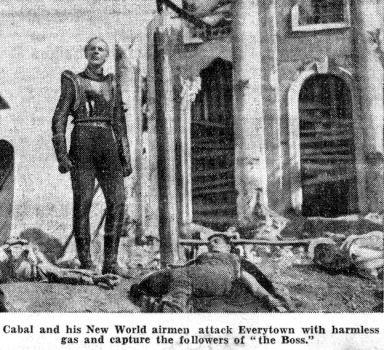

THE dark figure of Cabal appears through the swirl. He is wearing his great mask again and there is no sign of collapse about him. CABAL: " Your sentries seem to have gone to sleep. So I came out. . . . All the town is going to sleep. . . . You made us do it." The Boss, by this time, is sprawling insensibly. All the rest are lying insensible. There is a pause and then Cabal speaks. " And now for the World of the Airmen and a new start for mankind."

MARY is in a sitting position at the foot of the post to which she was tied, and Roxana is grouped very gracefully across her feet. The Boss sprawls on his face in the foreground with his clenched fist outstretched. Harding droops from his post. Burton, a little further off, lies on a heap of rubble, and beyond are soldiers and attendants. Cabal comes nearer to the group. " You might he more comfortable, Harding," he says, and releases the ropes, lowering the inanimate Harding into a sitting position. " So." Then he turns to the two women. " Well, my dears, you must sleep for a time. There's nothing more to be done." He stands looking at them. Close up of the two women's faces in repose. Mary is quietly peaceful. Roxana, even when she is insensible, contrives to be attractive. Cabal's voice is heard. CABAL : "Mary. And Madame Roxana ! Queer contrast. Madame Roxana. A pretty thing and a very pretty thing and what's to he done with this very pretty thing ? The eternal adventuress. A common pretty woman who doesn't work. A lady! She has pluck. Charm. Brains enough for infinite mischief. And a sort of energy. She'll play her pretty eyes at men to the end of her time. Now the Bosses go the way of motley grubbers. I suppose it will he our turn. Wherever power is, she will follow. "And let me confess to you, young woman, now that you can't hear me or take any advantage of me, that considering my high responsibilities and my dignified years, I find you a lot more interesting and disturbing than I ought to do. Men are men. you said, to the end of their days. You get at us. "I wish we could keep you under gas always. There is much to be said for the harem idea. Must you still be up to your tricks in our new world?" He adds : " The new world, with the old stuff. Our job is only beginning."

Civilisation Again !

Dawn breaking over Everytown. Dawn sky. Vista of a side street. Sleeping figures lie scattered about. Gordon and a knot of companions, several young airmen and two women, also in black leather, come through the ruins. They are no longer masked. One of them tears down a rosette flag in passing. FIRST YOUNG AIRMAN : " They'll sleep for another day. " SECOND AIRMAN: " Well, we've given 'em a whiff of civilisation at last." FIRST AIRMAN: " Nothing like putting children to sleep when they are naughty. " On the outskirts of the town, wondering country people in their coarse canvas clothes and sabots are seen coming down the hillside against the familiar skyline. People coming into the Square, which is littered with sleepers. Some of the sleepers are beginning to stir. A bunch of the new airmen in their black costumes, but not masked or helmeted, appear and walk across the scene.. People staring at the airmen, the backs of the unkempt heads very big in silhouette in the foreground of the picture. It is decadent barbarism watching the return of civilisation.

RETURN to the council room at the aerodrome at Basra. Much greater activity is now seen through the window. Big lorries are running about. People go to and fro. Aeroplanes of novel type are going up in groups of seven, squadron after squadron. The table is now covered with maps and a group of secretaries stand ready to give any help. Costumes, very slightly "futuristic," severe, and mostly mechanics' or air costume. Cabal is a dominant figure beside the chairman. CABAL, leaning over a map : "This is how I conceive our plan of operations. Settle, organise, advance. This zone, then that. At last wings over the whole world and the new world begins. More and more it will become a round-up of brigands. . . . "

Over a ruinous landscape, brigands with flags and old military uniforms in flight as the new aeroplanes overhead bomb them. The bombs explode and gas overcomes the brigands. Sky writing by the new planes : SURRENDER. Brigands crawl from hiding place and surrender, hands over their heads. Brigands run out from the houses of another town as the aeroplanes approach. They surrender. The sky dotted with the new aeroplanes. Hundreds of men drop from the sky with parachutes. The brigands stand waiting. A line of prisoners marching. They carry regimental flags. They are the last ragged vestige of the regular armies of the old order. It is the end of organised war at last. A group of the new airmen watch their march-past. Overhead the new aeroplanes are hovering.

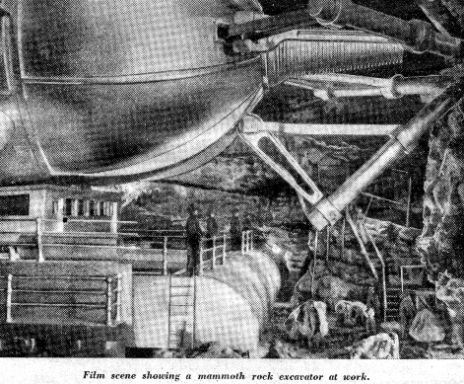

Life in 2054

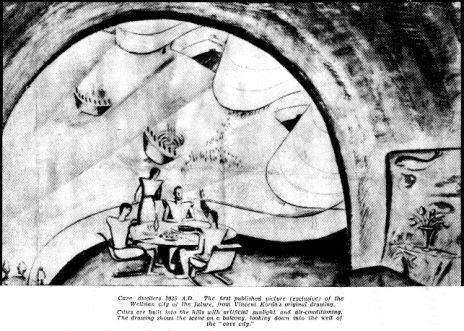

THE object of this Part is to bridge, as rapidly and vigorously as possible, the transition from the year 1970 to the year 2054. An age of enormous mechanical and industrial energy has to be suggested. The shots dissolve rapidly on to one another, and are bridged with enigmatic and eccentric mechanical movements. The small figures of men move among the monstrosities of mechanism, more and more dwarfed by their accumulating intensity. An explosive blast fills the screen. The smoke clears, and the work of the engineers of this new age looms upon us. First, there is a great clearance of old material and a preparation for new structures. Gigantic cranes swing across the screen. Old ruined steel frameworks are torn down. Shots are given of the clearing up of old buildings and ruins. Then come shots, suggesting experi-ment, design and the making of new materials. A huge, power station and machine details are shown. Digging machines are seen making a gigantic excavation. Conveyor belts carry away, the debris. Stress is laid on the work of excavation because the Everytown of the year 2054 will be dug into the hills. It will not be a skyscraper city. A chemical factory with a dark liquid bubbling in giant retorts works swiftly aid smoothly. Masked workers go to and fro. The liquid is poured out into a moulding machine that is making walls for new bitildings. The metal scaffolding of the new town is being made and great slabs of wall from the moulding machine are placed in position.. The lines of the new subterranean city of Everytown begin to appear, bold and colossal. Swirling river rapids are seen giving place to a deep controlled flow of water as a symbol of material civilisation gaining control of nature. Flash the date A.D. 2054. A loud, querulous voice breaks across the concluding phase of these scenes of " transition."" I don't like these mechanical triumphs."

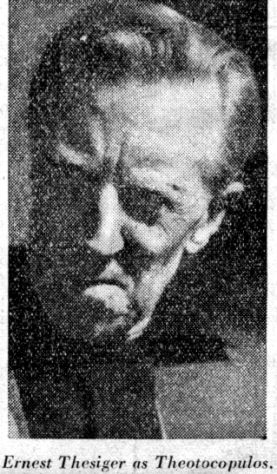

He is seen to be sitting at the foot of a great mass of marble. He is wearing the white overalls of a sculptor and carries a mallet and a chisel. A second sculptor, a bearded man, comes into the picture. " Well, what can we do about it?" THEOTOCOPULOS, as if he reveals the most obscure secret, " Talk." The bearded man shurgs his shoulders and grimaces humorously as if towards a third interlocutor in the auditorium. THEOTOCOPULOS explodes : " Talk. Radio is every-where. This modern world is full of voices. I am going to talk all this machinery down." The BEARDED MAN : " But will they let you?" THEOTOCOPULOS imperiously : " They'll let me. I shall call my talks Art and Life. That sounds harmless enough. And I will go for this Brave New World of theirs—tooth and claw." 110 Looks Back A LARGE space, rather than a room, partaking of the nature of a conservatory and large drawing-room. There are neither pillars nor right-angle joints. The roof curves gently over the space. Beautiful plants and a fountain in a basin. Through the plants one catches a glimpse of the City Ways. An old gentleman of 110 or there abouts, but good-looking and well-preserved, sits in an arm-chair. A pretty little girl (8-9) lies on a couch and looks at a piece of apparatus on which pictures appear. It has a simple control knob. Some strange pet animal, perhaps a capuchin monkey, is playing with a ball on the rug. A doll in an exaggerated costume of the period lies on a seat. GIRL : "I like these History Lessons." The apparatus is showing Lower New York from above—an aeroplane travelogue. LITTLE GIRL: "What a funny place New York was—all sticking up and full of windows." OLD MAN : " They built houses like that in the old days." LITTLE GIRL : " Why?" OLD MAN : "They had no light inside their cities as we have. So they had to stick the houses up into the daylight—what there was of it. They had no properly mixed .and conditioned air.' He manipulates the knob and shows a similar view of Paris or Berlin. " Everybody lived half out of doors. And windows of soft brittle glass everywhere. The Age of Windows lasted four centuries. " The apparatus shows rows of windows, cracked, broken, mended, etc. It is a brief fantasia on the theme of windows done in the Grierson style. OLD MAN : " They never seemed to realise that we could light the interiors of our houses with sunshine of our own, so that there would be no need to poke our houses up ever so high into the air." LITTLE GIRL: " Weren't the people tired going up and down those stairs ?" OLD MAN : " They were all tired and they had a disease called colds. Everybody had colds and coughed end sneezed and roll at the eyes." LITTLE GIRL: " What's sneezed?" OLD MAN : " You know. Atishoo!" The little girl sits up very greatly delighted. LITTLE GIRL: " Atishoo. Everyone said Atishoo. That must have been funny." OLD MAN: "Not so funny as you think." LITTLE GIRL.: " And you remember all that, great-grandfather?" OLD MAN : " I remember some of it. Colds we had and we had indigestion too—from the queer bad foods we ate. It was a poor life. Never really well." LITTLE GIRL: " Did people laugh a lot?" OLD MAN : " They had a way of grinning at it. They called it humour. We had to have a lot of humour. I've lived through some horrid times, my dear. Oh! Horrid!" LITTLE GIRL : " Horrid! I don't want to see or hear about that. The Wars, the Wandering Sickness, and all those dreadful years. Noise of that will come again, great-grandad? Ever? " OLD MAN : " Not if progress goes on." LITTLE GIRL : " They keep on inventing new things now, don't they? And making life lovelier and lovelier? "

To the Moon

OLD MAN : " Yes . . . Lovelier and bolder . . . I suppose I'm an old man, my dear, but some of it seems almost like going too far. This Space Gun of theirs that they keep on shooting." LITTLE GIRL: " What is this Space Gun, great-grandfather?" OLD MAN : " It is a gun they discharge by electricity—it's a lot of guns one inside the other—each one discharges the next inside. I don't properly understand that. But the cylinder it shoots out at last goes so fast that it goes—swish—right away from the earth. " LITTLE GIRL (entranced) : " What. Right out into the sky! To the stars? " OLD MAN : " They may get to the stars in time, but what they shoot at now is the Moon." LITTLE GIRL : " You mean they shoot cylinders at the moon! Poor old Moon ! " OLD MAN : " Not exactly at it. They shoot the cylinder so that it travels round the other side of the moon and comes back, and there's a safe place in the Pacific Ocean where it drops. They get more and more accurate. They say they can tell within twenty miles where it will come back, and they keep the sea clear for it. You see ? " LITTLE GIRL : " But how splendid. And can people go in the cylinders? Can go when I grow up? And see the other side of the moon ! And plump back ker-plosh ! into the sea ! " OLD MAN : " Oh! They haven't sent men and women yet. That's what all the trouble's about. That's what Theotocopulos. is making the trouble about." LITTLE GIRL : " Theo—cotto— " OLD MAN : " Theotocopulos. " LITTLE GIRL : " What a funny name! " OLD MAN: "It's a Greek name. He's the descendant of a great artist called El Greco. Theolocopulos—like that." LITTLE GIRL : " And he makes trouble you say ? " OLD MAN : " Oh, never mind. " LITTLE GIRL : " It wouldn't hurt to go to the moon? " OLD MAN : " We don't know. Some people say yes—some people say no. They've sent mice round. " LITTLE GIRL : " Mice that have gone round the moon ! " OLD MAN : " They get broken up, poor little beasties! They don't know how to hold on when the bumps come. That's why there's all this talk of sending a man, perhaps, He'd know how to hold on . . ." LITTLE GIRL : " He'd have to be brave, wouldn't he . . . ? I wish I could fly round the moon. " OLD MAN : " That in time, my dear. Won't you come back to your history pictures again ? " LITTLE GIRL : " I'm glad I didn't live in the old world. I know that John Cabal and his airmen tidied it up. Did you see John Cabal, great-granddad ? " OLD MAN : " You can see him in your pictures, my dear. " LITTLE GIRL : " But you saw him when he lived. You really saw him ? " OLD MAN : " Yes. I saw the great John Cabal with my own eyes when I was a little boy. A lean brown old man with hair as white as mine. " A still of John Cabal is shown as we saw him in the council at Basra. The OLD MAN adds : " He was the grandfather of our Oswald Cabal, the President of our Council. " LITTLE GIRL : " Just as you are my great-grandfather? "

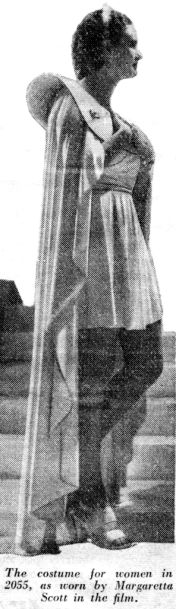

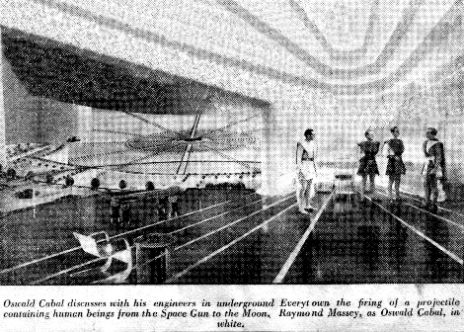

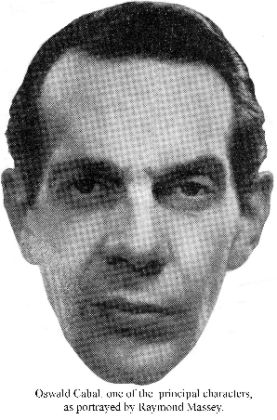

OSWALD CABAL is seated in his private room in the administrative offices of the City of Everytown. The room is of the same easy style of architecture as the preceding scene. There are no windows and no corners, but across a kind of animated frieze, a band of wall, above Cabal's head, there sweep phantom clouds and waves, waving trees, clusters of flowers and the like in a perpetual silent sequence of decorative effects. There is a large televisor disc and telephone and other apparatus on the desk before Cabal. Oswald Cabal is a calmer younger-looking version of his ancestor. His hair is dark and, like all hair in the new world. trimly dressed. His costume is of a white silken material with very slight and simple embroidery. In its fineness and white ness and in its breadth across the shoulders it contrasts acutely with the close black aviator costume of John Cabal.

The First to the Moon

Cabal says to an unseen interlocutor: " Then I take it this Space Gun has passed all its preliminary trials and that nothing remains now but the selection of those who are to go." The picture broadens out, and we see that Cabal is not alone. He is in conference with two engineers. They wear dark and simple clothes in the broad-shouldered fashion of the age—not leather working-clothes or anything of that sort. In an age of mechanical perfection there is no need for overalls and grease-proof clothing. One sits on a chair of modernist form. (All furniture is metallic.) The other leans familiarly against a table. First Engineer: " That's going to be the trouble." Second Engineer: " There are thousands of young people applying—young men and young women. I never dreamed the moon was so attractive." First Engineer: " Practically the gun is perfect now. There are risks, but reasonable risks. And the position of the moon in the next three or four months gives us the best conditions for getting there. It is only the choice of the two now that matters." Cabal: " Well?" Second Engineer: " There are going to be difficulties. That man Theotocopulos is talking on the radio about it." Cabal: " He's a fantastic creature." Second Engineer: " Yes, but he is making trouble. It is not going to be easy to choose these young people." Cabal: " With all those thousands offering?" First Engineer: " We have looked into thousands of cases. We have rejected everyone of imperfect health. Or anyone who had friends who objected. And the fact is, sir—. We wish you would talk to two people. There is Raymond Passworthy of General Fabrics. You know him?" Cabal: " Quite well. His great-grandfather knew mine." First Engineer: " And his son." Second Engineer: " We want you to see the son, sir—Maurice Passworthy." Cabal: " Why ?" First Engineer: " He asks to go." Cabal: " With whom?" Second Engineer: " We think you had better see him. He is waiting here." Cabal considers and then lifts his gauntlet and touches a spot on it. A faint musical sound responds. He says: " Is Maurice Passworthy waiting . . . Yes. . . . Send him up."