| RAF Service : More Memories | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||

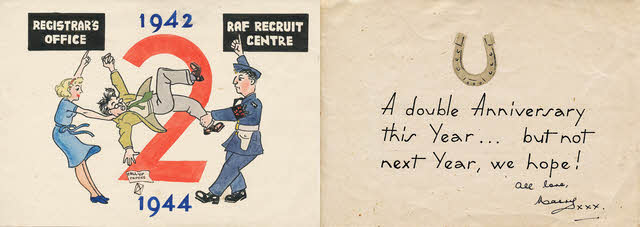

1944, A double anniversary of a tug-of-war year between matrimony and the R.A.F.

During the TV news recently, a map flashed on the screen showing the location of Ingoldmells, which roused an old RAF memory. There used to be a wartime radar station in that vicinity, whose name began a popular ditty among radar mechs on convivial occasions... sung to the tune of "Jingle Bells" it reeled off the names of a galaxy of coastal stations, starting thiswise: "Ingoldmells, Ingoldmells, The list was never-ending (we radar mechs were a well-travelled/pushed-around lot) and, in retrospect, I guess the detailed and rash listing of all these secret establishments would have been a gift to any spy within hearing distance ! Indeed, looking back on those fraught times, I am astounded by how "easy-going" secruity often was—during 1944, I met an American science fiction fan over here with the US forces; we got together in Lincoln, and he and his mate returned with me to Cranwell camp, where they stayed over the weekend in our hut, sleeping in beds temporarily vacated by people on leave, feeding with us in the canteen and generally using camp facilities. But on one queried their presence in all that time. ■ Letter to Peter Ashford, May 2004. Well, I hope that some of your queries about what fans wore in 1937 were answered when you saw the snapshots I sent in for "Embryonic Journey". As Arthur Clarke celebrated his 20th birthday that year, you'll have to try a few years earlier to catch him in short pants... The big question now, as raised by Mal Ashworth, seems to be why Ego was the only fan wearing an overcoat at the Con. North Kelsey looks really isolated on the map - I wonder which little blob of black you live in - and I guess it is when the snow comes down. There's a lot of countryside around you and it looks pretty flat. My memories of Lincolnshire, dating back to a wartime stay at Cranwell, are that it's big & flat & covered with air fields. Happen you don't have all those air fields now, which is as well if you go driving around in all these giant vehicles. There were occasional happy fannish times at Cranwell. I met up with several American fans in the services including Gus Willmorth, who spent a few days in our billet on one occasion without any queries from the security police. But most of the time I seem to have spent all my 'spare' time sloping off home on crafty weekends, hitching a lift on stray RAF lorries (there were a lot of 'em on the roads carting mangled bombers for cannibalisation) or falling back on the services of the LNERailway and the mighty Lincolnshire Road Car Company. I recall one occasion, when the raids had been frequent and trains delayed, a mighty swarm of RAF types surrounded the Lincoln depot of the LRCC way after the time had passed for the last bus out, and a lonely inspector was arguing with a rowdy mob clamouring to get back to the various camps before lights out, protesting that he couldn't get the drivers. He eventually retreated in the face of the opposition. The buses were occupied, volunteer drivers found and a convoy set off along the winding LincoInshire roads, dropping off troops as they passed a camp. I often wondered where those buses finished up, and whether they got back to the depot. ■ Letter to David Bell, 20/02/1987, printed in his zine The Eagle of the North Thanks for Eagle, in which I find myself cast in the unexpected role of Muse... I too find myself annoyed by the obscenity of pasteurised TV violence offered as entertainment. where Jokers like the A Team randomly spray automatic weapons to create havoc with the environment without, apparently, any corresponding effect on its inhabitants. My experience with Sten guns was that they were dodgy things to handle; mass-produced to low standards. In India, after VJ Day, we used them to go hunting - the occasional peafowl was a welcome addition to rations - and safety catches and rate-of-firing catches were so susceptible to mishandling, that the 'hunters' were often in more danger than the prey. As a raw & reluctant wartime recruit to the RAF, I hated handling weapons and had a low opinion of n.c.o.s in charge of weapon training & assault courses. (I did modify that attitude in the ensuing years when I realised just what these n.c.o.s had to contend with - especially in the practice ranges, coping with nervous idiots with semi-paralytic arms who lobbed live grenades too close for comfort, or even in the heat of the moment dropped grenades in the throwing bay immediately after pulling out the priming pin.) My later service experience of small-arms was limited since I became a radar mechanic, though while at Cranwell, doing maintenance at the radio school, I had a few uncomfortable experiences when we were visited by German fighters several times in the early morning hours. They dodged the radar defences by tagging behind a flight of returning bombers, and then dived down and used the approach road to do a firing run on the cluster of huts and aerial masts at the technical site. Some Browning guns were hastily rigged up at strategic points to try and cope with these surprise calls, and we had to report for extra defence duties. In view of our amateur status as Browning gunners, we were sent on individual courses for a week at a range at Langham in Norfolk. I was rereading some of the letters I sent home at the time and see that my turn came at the end of January when there was a thick white mist everywhere on the morning of my departure from Cranwell. (Typical Lincolnshire weather ?) That played havoc with the train service, but left me with a few free hours in Peterborough, waiting for connexions. Apparently I met another bloke on the way to the course who flogged me a 7/6d book token for 5 bob (the token was a gift and he needed the money more than books he said). So I acquired three Penguins, and still had sixpence change, as they say. The next train went straight through to Thursford, the nearest stop but started 35 minutes late and stopped at every hamlet en route. We shivered in an unheated comportment & watched the desolate snow-covered landscape creep past until darkness descended. There were a score or so RAF types, plus kit, already on the platform when we arrived. A large RAF lorry eventually arrived and we all piled into the back, then waited for half an hour before the WAAF driver decided to start for the camp. The engine, which had been ticking over all this time, promptly spluttered and conked out. The cause appeared to be an empty petrol tank, though by the time the tank had been filled, the engine had cooled down and wouldn't restart. So we spent the next half-hour manhandling the blasted lorry up & down the station yard in a fruitless effort to get it started. We suggested she rang up for another lorry, but with all the uncomplimentary remarks flying, around our driver turned obstinate and insisted we try to push the van on to the road to run down a hill see if that would get the engine running. So we shoved the thing out of the station yard and got stuck on the level crossing - it took ages to manoeuvre it on to the road, with complications when the gates tried to close on us for an approaching train! Our efforts proved unavailing, so our WAAF got on the phone. It turned out that no transport was available but hopefully another lorry might be passing later. After a hurried consultation, half a dozen of us stopped to unload all the kit from the broken down lorry, while the rest set out in search of a pub, a mile or so along the road. This was around 9.30 pm. Fifteen minutes later a lorry rolled up, crowded with bods going to Langham. We squeezed ourselves and all the gear aboard, and decided that that the pubcrawlers could be collected later. We were told that the camp was only 5 miles from the station - it seemed more like 60 with the lorry crawling at a snail's pace because of mist and icy roads. Langham is a 'dispersed' camp which means that there are bits of it every few miles - a godforsaken hole... We arrived at the office, signed on, and thankfully had some supper and hot drinks before being shown to our quarters; a damp, chilly, empty Nissen hut with a solitary stove in the centre, and a small supply of coke under the snow outside. Our blankets are worn-thin things after the full-sized issue at Cranwell - we slept in our clothes to avoid the all-pervading chill, after the other wanderers turned up around midnight. The next day was spent pulling Brownings to pieces, an art which I had already acquired at Cranwell, so things were not too bad. Maybe this place would not be so off-putting in the summer; we were fed up with the lousy weather and the inevitable bull of a course - my boots and buttons had not gleamed so brightly since my Redcar days. I still have memories of the ritual "naming of the parts"... "This 'ere is the sear, this 'ere is the sear spring, this 'ere is the sear spring retainer, this 'ere is the sear spring retainer keeper..." It sticks with you forever, like your service number, after all the parrotting. Fortunately, the weather cleared up when we were due to go on the beach practice ranges, and we had some sunshine, though the outlook remained bleak and wintry. Some brave pilot was found to fly an ancient biplane towing a drogue at which we were encouraged to fire live ammunition. I was wearing issue metal-rimed specs in those days, and as the gun fired, the recoil pushed my head into the padded sight with such force that I finished up half-blind because my specs were wrapped closely to my skull's contours. We were supposed to fire over a limited arc, your mate slapping you on the back once the target had passed these limits, so you stopped fire. I usually stopped in good time because of the urgent need to bend my specs back into shape again before continuing. But some blokes got so trigger-happy they went on firing despite being clouted vigorously, and had to be dragged bodily from the gun by a fantic instructor, before they shot off the tail-plane of the receding plane. Like you say, the ultimate responsibility lies with the person who pulls the trigger. Sorry about all the wartime reminiscences. Blame it on Mal Ashworth and the CONception. I was encouraged to read through old letters in search of fannish items and found myself catching up with wartime experiences that I'd half forgotten. Oh yes, and when the report on my course came through, I was recommended as a gunnery instructor. It took me a long while to live that down. But enough... ■ Letter to David Bell, 12 April 1987 Since I tracked down the whereabouts of Church Farm after first making your acquaintance, those little black blobs on the map of Lincolnshire have gradually begun to be transformed into a mental landscape after the revelations of goings-on in North Kelsey that have appeared in TEOTN over the past few months. I imagine most conscripted folk in the forces endorsed the 'never volunteer' principle. But most times, when services above and beyond the call of duty were demanded, we were not given any options about 'volunteering'. There were always means of making you volunteer, like the threat of all sorts of 'orrible consequences if you didn't volunteer. With me, I had problems whenever admin people found I had 'artistic talent'. Thus in one camp I soon found myself unwillingly scaling a large water tower with the object of painting a vast "Salute the Soldier" savings campaign poster. At another, I was co-opted to help out a WAAF Tracer in the Radio School, who couldn't keep up with the demand for drawings of circuit diagrams for instructional purposes. We really got that drawing office organised; one of the few times when volunteering brought some personal benefits; because we caught up with the backlog of work and got so far ahead of demand (without telling the admin office, natch) that we were able to take time off and get out of camp for a while. One of us stayed in the drawing office to cover up while the other sloped off. We got too organised, of course; we'd worked up to disappearing on long crafty weekend visits home and were planning longer periods of unofficial absence when I got a posting overseas. But it was good while it lasted! Which reminds me that while in India, at a transit camp, waiting for a posting after a stay in hospital, I got so bored that I rashly volunteered when a call came for 'ticket & sign-writers'. I expected that a few posters were wanted, but it turned out that the job was painting scenery and making props for the play Rope**. The camp CO was keen on amateur dramatics, and had organised the show in Bombay, so four of us were shipped out to a small makeshift theatre and left to get on with it after brief instructions from the local ENSA wallah. I remember assembling a ramshackle box to hold the body from an old packing case and canvas, and doing a great job of painting the graining so that it looked like real wood off-stage. The ENSA bloke was so thrilled with our efforts that he promised to wangle us on to his staff permanently. Inevitably my expected posting promptly came up and I was despatched far from the fleshpots of Bombay... ■ Letter to David Bell, 24 July 1987 ** Rope by Patrick Hamilton is a gruesome thriller based loosely on the Leopold and Loeb murder case. Two students murder a fellow student as an expression of their supposed intellectual superiority. They hide his body in a chest then hold a party for the deceased's friends and family, using the chest as a table for a buffet.

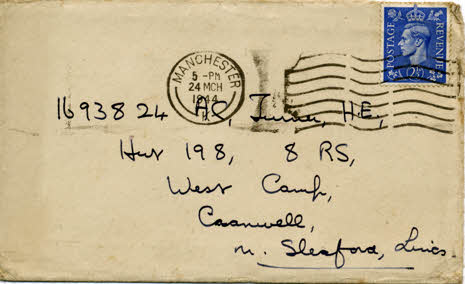

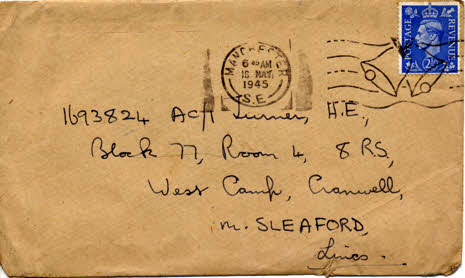

Envelopes from letters sent to Harry Turner at RAF Cranwell in 1944 (above) and in 1945 (below). Note the Victory cancellation on the May 1945 letter.

Had a note from the India Tourist Office saying that they 'only provide tourist information and are unable to send historical details of the places you have asked about'. However, they've recommended Forts &p Fortifications In India by A.P. singh, and The Forts of India by Virginia Fass, and passed on the address of 'Books from India'. No mention of maps though, alas. Purandhar was used as a 'master' station for the Gee radar chain in the Western Ghats, and I spent several weeks there before departing on a tour of the various 'slave' stations in the vicinity. Purandhar fortifications were halfway up a twin-peaked hill; we were limited on one side that had been used as a convalescent depot before the RAF moved in, a black-stone edifice that looked out over the ghats and was immediately Shangri-la. Most of the site was out-of-bounds as internees were kept up there during the war, and fraternisation was forbidden. There was a Hindu temple on one peak, and we had a Nissen hut and aerial as the technical site on the other. It was almost a mountaineering training course to get up there; usually one volunteered for a 24-hour stint of duty, to minimise the effort of getting up and down. But it was easy to see how the Marathas enjoyed being top dog from such vantage points. My geography of the area was confused at the time. Forty odd years later, it's even more confused and just to get my bearings, I must try and locate a map. The roads from Pune (I bow to current usage) were eligible to appear on a map -- though the surfaced stretches were short enough -- and the names of the various areas in which the radar sites were sited were definite enough. Alas, the only other place that appears on the maps consulted is Mahabaleshwar, which used to be the hill station refuge of the Bombay governor during the hot season. This was on the edge of the ghats; from the vfantage point of several rocky outcrops you could watch the sun go down, in the clear post-monsoon sky, until there was a glaming line of reflection stretching momentarily along the horizon -- I think we were about 30 miles from the sea. ■ Letter to Steve Sneyd, 9 Feb 1989 The library located a copy of the Virginia Fass book, The Forts of India (Collins, 1986), definitely a picture book for reinforced coffee tables, but worth dipping into. There's a short chapter on the Maratha forts, with some pictures of Purandar and adjacent places, and more details of Shivaji's exploits against the Mughals, but I get the impression that they don't attract so many tourists as the more picturesque structures further north, and are not so accessible to the casual tourist. All in all, a pricey book at £30 but worth looking at if you get it through the library system. Was amused to read in one of the travel books I've been referring to that the highest point at Mahableshwar, Arthur's Point, was used as HQ for a jungle training course by the army in WW2 - our later occupation with the Gee chain equipment is ignored! So that's another reason why I should get my bit of history on paper before it's completely forgotten. ■ Letter to Steve Sneyd, 22 April 1989 Day-dreaming the other day about a VJ-Day reunion with some of the folk I got to know in India... Nick Cropper and Jack Loveman I met on the boat going over, and our paths kept crossing thereafter; And lots more: it would have been a big party! The sobering thought is that two of the most welcome people—Jack and Derek—would now be ninetyish. Gulp. Perhaps I'd better just go on remembering them as I knew them. The temptation is to think of those five years in the RAF as lost time, wasted time. And yet I find my memories increasingly dominated by the experience. Which explains why I still have an urge to reminisce and pin down a few more details. ■ Letter to the Varleys, VJ Day 1995 The trouble with India is not the heat but the humidity. I was lucky in that most of the camps I was at were up in the hills, where you get dry heat, and a cooling off period during the night. The main problem was keeping an eye on the length of time you were exposed to the sun, especially in the Nilgiris, some 6,000ft up, where the sunshine seemed pure ultra-violet... But I enjoy dry heat, and can be relatively lively up to the 80s, but admit to wilting somewhat when temperatures occasionally soared into the 90s. However, at sea-level, places like Bombay and Madras, you sweat something terrible because of the humidity: I just had to learn to slow down, and amble, instead of charging around as used to be my want. I tan easily, and that helps; if you're blonde and fair-skinned it could be hell. Prickly-heat, an itchy goose-pimply rash turned on by abused sweat-glands, was a common complaint that just had to be put up with, like the common cold. Once I acquired my tan, I never had any problems with prickly-heat. But it was never very pleasant being out and active, and sweating profusely, and the more you drank, the more you sweated. There was no let up at night as it didn't cool off and you woke in sweat-soaked sheets. if you were fortunate enough to be able to get a cold shower, you never seemed to be able to get dry, because you started sweating again with the exertion of wielding a towel. I have a decided conviction that I was meant to live in a warmer clime than prevails in North-East Cheshire. ■ Letter to the Varleys, 29 July 1996 The Great RAF Strike Riffling thru the RTimes I see there's a "Secret History" prog on C4 on Thursday evening purporting to reveal all about the Great RAF Strike of 1946... Wow, that I must watch! (Funny, no-one came to interview me...).

That prog about the RAF Strike certainly struck responsive chords all over the place; the memories really came flooding back. I touched on the matter in "Just one of those days...", which I fancy I passed on to you, and there are other passing references in a piece about my stay at Mahableshwar, at the time of the strike. I fancy I'll be doing a piece solely devoted to the mess-up of demob arrangements and the feeling that we'd been conveniently forgotten and left out of calculations when the Far East war ended so abruptly.

Letter to the Varleys, August 1996 A GOOD HOLIDAY? As regards the RAF Strike, it started from general resentment at the slow pace of demob, when increasingly people were left kicking their heels, as the military effort ran down. The original promise that demob priorities would be established by age and length of service was soon distorted because all sorts of stipulations were made about retaining technical tradesmen, and people in jobs like nursing or catering, found they were classed as essential, and pushed back in the queue, while others, e.g. newly-trained air crews, with no active service but completely redundant with the end of the war, were being demobbed early. Then it became apparent that the army and navy had a faster rate of demob than the RAF, so things really started to fizz. The old colonial regimes faced up to demands for independence once the fighting had stopped, and there was talk that the RAF would be used to fight the "terrorists" in SE Asia. Which was when it all blew up, and folk refused to go on parade or salute officers in several of the bigger camps; thanks to the teleprinter network and radio stations being operated by the people striking, they had control of communications, and the word, and action, spread fast... Matters were complicated by some isolated units of the Indian Air Force and Navy also taking action; that was hailed as mutiny and put down forcibly. There was some talk of the army being sent into RAF stations, but there were so many people involved, technically civilian conscripts, it was not a likely proposition, which was why the word "strike" was used instead of "mutiny" (except for a few diehards who wanted to use a bit of force and start setting examples...). This was in January 1946. And it was all over by the end of the month, with promises that demob would be speeded up. I doubt if it made any difference in the long run. There were no airlifts in those days (except for the privileged few), and all transport was by sea. A few groups got home quicker following the upset, and then things slowed up again because of the shortage of shipping space. I was hanging about Bombay for ages after my group had reported there for embarkation, and didn't get back and demobbed until the end of November 1946. I have a memory of finally escaping from the demob camp, in blue sports coat and gray flannels (all the decent suits in my size had long gone by the time I got kilted out), arriving at Victoria Station and joining a bus queue, where my tan was balefully eyed by an aged couple in front of me, and a loud voice grumpily commented that "some buggers can afford to have a good holiday". A remark that rankles still. ■ Letter to the Varleys, Summer 1996 "CRAFTIES" Your suggestion that the station pic could be Peterborough sounds likely: that angled platform roof didn't fit in with my memories of the old M/cr and L'pool stations. During my stay at wartime Cranwell, I spent considerable time changing trains at Peterborough station, but no memory of its geography remains, probably because nothing ever happened beyond the usual delays. It was different with other stations: a fair number of trips home during RAF service were "crafties", without a pass, dodging off when there was a convenient gap in duties, and from hearsay you got to know which stations were haunted by Special Police, and ways of dodging their attentions. Like at London Road (as it was before it became Piccadilly), I recall that if it was an unofficial journey, it was essential to dodge through the barrier, get out on to the approach, and whizz down a circular staircase that used to be there, opening on to London Road, before any passing military police noticed I hadn't got my respirator, and wanted to see my pass. (If you tried to get out of camp with your respirator, the guardroom wanted to check you had a pass). What a complicated life it was... And I have vivid memories of old B'ham New Street, with all the platforms connected by a central bridge, swarming with SPs looking out for dodgy travellers. When I was stationed there on a radio course (and in civvy billets) we used to take great pleasure in keeping the SF's busy checking our ID as we walked across, in the hope that it gave someone on a "crafty" chance to dodge past undetected. Yet there were some stations, like Sheffield, that were extensively used by AWOL rail travellers crossing the Pennines without any hindrance: I often wondered if some authorities deliberately turned a blind eye to a certain amount of undercover travel. What the hell got me started on that bit of Memory Lane? Oh yes, your photo. Your suggestion that the photographer was Eric the Bent seems likely, as he was close to the Shorrocks in those days, and likely to be one of the party. Right, so that's sorted until any facts to the contrary turn up! All, there's still that fella in the trilby... ■ Letter to Brian Varley, October 1998 SWELTERING! Alistair Cooke dwelt on the soaring temperatures across the US the other week and reminded me of a visit to the RAF base camp at Poona when prevailing noon temperatures were in the upper 90s—walking out of a building into the sunlight was like walking into a blast furnace. I spent several blissful afternoons haunting the air-conditioned mini-cinema at the nearby aerodrome (free to RAF personnel and, mercifully, with a daily change of programme!). ■ Letter to Brian Varley, July 1999 |

|