| Romiley Jazz Archive #1 | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

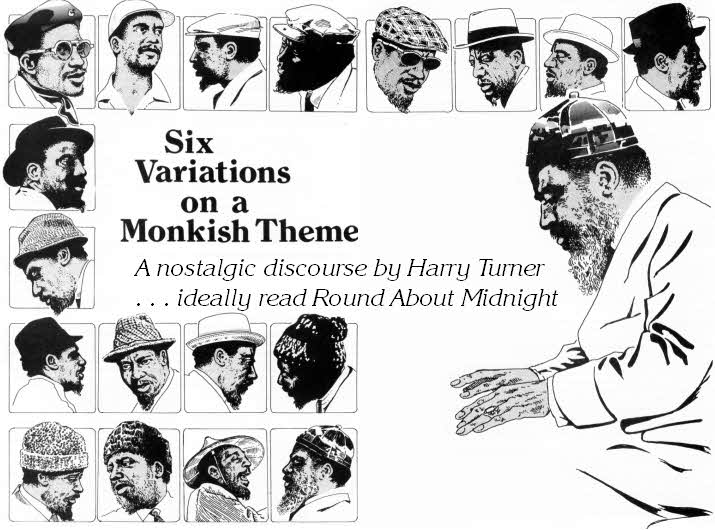

For a period, he appeared in felt hats, from the sedate and sombre to the wildly informal. Even a spell with a wide-brimmed sombrero. Monk’s changing headgear became an obligatory fashion note for the diligent jazz reporter. Thus LeRoi Jones was careful to mention that for his successful 1957 date at the Five Spot Cafe, Monk appeared in a “stingy-brim version of a Rex Harrison hat”. While Dan Morgenstern, reviewing a concert in Carnegie Hall, commented that “an added attraction was Monk’s splendid white Texas-styled hat, an exact copy of LBJ’s”. On his European tours of the 60s Monk produced some modish Astrakhans, and a lambswool winter hat from Helsinki. A trip to the Far East meant, inevitably, a coolie hat. On a world tour with the Giants of Jazz in 1971, when he made his last trio recordings for Black Lion in London, he favoured a silk mandarin skull cap, acquired in Tokyo. Gerald Lascelles, jazz critic, writing in Jazz Journal about one of Monk’s British tours, confessed to spending considerable time trying to relate Monk’s choice of headgear to his mood, and to his music. Alas, he reached no firm conclusions. Could be the maestro just enjoyed wearing funny hats... When he spoke at Monk’s funeral, George Wein told how Monk had been followed on a European tour by the reporter doing the cover story for Time magazine. Every day for all of three weeks Monk came out of his room wearing the same hat. At the end of the tour, he appeared sporting a different hat, and when the reporter asked why the change, Monk’s dry response was that you can’t wear the same hat every day...

The Newport Jazz Festival, Jazz at the Philharmonic, Jazz from a Swinging Era, the Basie and Ellington bands, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Sonny Stitt, Dave Brubeck, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Erroll Garner, Gerry Mulligan, Thelonious Monk and Art Blakey... most of them stopped off at the Free Trade Hall. And local promoters encouraged visits from individual American players – the likes of Henry Red Allen, Earl Hines, Buck Clayton, Bud Freeman, Pee Wee Russell, Ruby Braff, Teddy Wilson, Ben Webster, Don Byas – to front British groups. In 1963, even the Beaulieu International Jazz Festival was diverted to the cavernous halls of Belle Vue . So much talent; so much music. The problem was getting around to listen to it all and a good part of my leisure was devoted to the ffort. Only a few years earlier, around the mid-50s, I had begun to dream ambitiously of a jazz collection of new-fangled LPs to replace the many 78s casually acquired since prewar days. Came the day when my battered radiogram was replaced by state-of-the-art hi-fi separates and a massive Wharfedale speaker which most visitors assumed was some sort of room heater. The record reviews were studied diligently and the domestic budget frequently imperilled by surreptitious buying of essential records. While still happily listening to the music of earlier decades I began to sample the sound of contemporary jazz developments with increasing interest. One unfamiliar name among the many that cropped up in the reviews caught my fancy. "Thelonious Sphere Monk". A resounding name, one not easily thrust aside or forgotten once heard. I was intrigued to find that reviewers’ comments about him and his music ranged from ridicule to wild enthusiasm. To get my bearings, I checked with acquaintances. They proved non-commital, evasive or downright dismissive, quoting extant tales of the Mad Monk, high priest of bebop at Mintons in the 40s, a poseur who lacked all piano technique and hid behind weird chords and zombie music... a general thumbs down. Looking back, it must be said that the war between ‘trad’ fans and ‘modernists’ was still being waged in the provincial jazz circles I frequented. Trad supporters simply closed their ears to post-war sounds; many modernists were too dazzled by the genius of Charlie Parker, even several years after his death, to appreciate that a plurality of jazz styles had already evolved with bop. I had to hear Monk and make up my own mind. There wasn’t overmuch of his music in the shops – a few EPs and LPs on the Esquire and London labels, culled from American Prestige and Riverside sources. I took the plunge with an album titled Thelonious Monk plays the music of Duke Ellington. Mind you, the sleeve note on this London LP was strangely apologetic, explaining at length that the session had been given the lure of Duke’s name as a marketing ploy to attract customers who might otherwise have passed by. It’s not often that salesmen take you into their confidence like that; I found it an odd comment on the confusion of the time that Monk’s own music was somehow regarded as the supreme obstacle to his wider acceptance... They really needn’t have worried. I was won over at first hearing, responding to Monk’s spare, lucid, percussive piano playing and, once attuned to his dissonances, enjoyed it all. This 1955 trio – Monk with Oscar Pettiford and Kenny Clarke – play together marvellously: from the bluesy, relaxed, slightly off-key playing of Black & Tan Fantasy, the spaced out version of Caravan, to an account of Sophisticated Lady revealing a snappier, more brittle side of her personality than ever Ellington essayed. To contrast with these fine swinging tracks by the trio, there’s a pensive solo piano exploration of Solitude which perfectly expresses the mood of the piece. Duke and Monk both have roots in Harlem piano, and on this LP Monk plays homage to the Master in the best way he knows. (Much later, someone told me to listen to the track Mr J.B. Blues, one of the Ellington-Blanton duets of October 1940, to hear a surprising foretaste of Monk’s piano!). Monk’s radical approach to jazz piano seemed sheer delight. My ears had already been attuned by musical assaults on other fronts; the percussive pianism of Stravinsky and Prokofiev in pieces of the 20s, and those American mavericks of the piano, George Antheil and Charles lves. lves, especially, a nonconformist who discarded his early training at the piano to experiment and adopt an ‘untutored’ intuitive approach, had strong affinities with Monk, who seemed to follow a similar path within the jazz tradition. Not long after, I had The Unique Thelonious LP on my turntable. This was, in effect, the second stage of the Riverside ‘Monk-indoctrination’ course, presenting Monk playing more familiar tunes by other composers. Recorded in 1956, this trio has Art Blakey replacing Clarke on drums. Monk approaches the tunes as points of departure for more radical recompositions on piano, playing throughout with subtle economy (not a note wasted!) and deceptive simplicity. He takes ribald but respectful liberties with Tea for Two and Honeysuckle Rose, then treats Darn that Dream and You are too beautiful with moving tenderness, expressing feelings far removed from the stock sentimental pretensions of your average popular lyric. He starts an unaccompanied Memories of You with a certain hesitancy, feeling his way through the theme before moving into a personal interpretation that is sheer delight. Highlight of the set is Just you, just me, where his rhythmic variations are taken at a lively pace, with active participation from Pettiford and Blakey. Having survived thus far, I threw caution to the winds and sought an album of Monk’s own compositions. Monk’s Moods, from Prestige trio tracks dating from the early and mid-SOs, offered seven Monk originals plus three Monk renditions of pop songs. Mind-blowing stuff..., the house throbbed with the sound of Blue Monk for days, until divorce proceedings were threatened. I’ve now lived with that particular version of Blue Monk for over thirty years, played it at an umpteen record recitals and talks and it still, to my ears, sounds as fresh and exciting as on that first hearing. Monk and Art Blakey, the drummer on the session, enjoyed an almost telepathic musical relationship. In an interview shortly before Monk’s death in 1982, Blakey was quoted as saying that “we were born on the same date, same year, and we’ve always been, like, together... He’s more like me than anybody I ever met”. And it shows in their music making. Monk has made several versions of Blue Monk – one is heard in Bert Stern’s colourful film documentary of the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, Jazz on a Summer’s Day – but this first recording, made in 1954, is a masterpiece, a jazz classic. The LP also features Monk and Blakey in Bye-ya, a Latin-American romp of a duet; Little Rootie Tootie, where jarring single notes and clashing chords conjur up the progress of a little train careering jauntily along the track; and a typically acidulated Sweet and Lovely. Max Roach takes over drums in a cheery set with much background vocalising and a slightly out-of-tune piano (imparting a teeth-on-edge start to These foolish things !). There’s a buoyant account of Bemsha swing; Trinkle tinkle, with its shimmering clusters of edgy notes from Monk, and forceful interjections from Roach to provoke fresh cascades; with a bonus of a piano solo with Monk prodding the theme of Just a gigolo through idiosyncratic subtleties to a hesitant, hanging finish.

Monk had listened hard to many pianists in his formative years in New York. While he admitted to no major influence, on his occasional astringent send-ups of stride style, he gives a reverent nod toward the Harlem masters of the art – James P. Johnson, Willy the Lion Smith, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington – sharing the joke. New York was home to Thelonious Monk. He had a great affection for the city, knew it well, since for twenty years, before success caught up with him, he had to scuffle for jobs, playing in dance hails and bars. “You want to know what sound I put in my music – well, you have to go to New York and listen for yourself,” he told Valerie Wilmer in an interview. And soprano-sax player Steve Lacy, with the insights gained from spending over a decade studying and playing Monk’s music, suggests that the whole body of work is a revealing self-portrait of Monk, set against a background of New York, and all the people Monk knew.

A long-time jazz collector, Lion at first issued traditional and swing items, but when the recording ban ended in 1944 he became interested in the ‘new sounds’ of the younger players. He hired tenor man Ike Quebec as musical adviser, and gave Monk his first break as leader, playing his own music, at the end of 1947. Monk came to the Blue Note dates with a stockpile of his compositions. Alfred Lion said later that they had difficulty initially finding musicians who could play with Monk because of his departures from the prevailing bop-dominated style. Consequently the results are mixed, musically, though the pianist is a delight throughout. The musicians had to learn what he wanted largely by ear, and the early ensembles do not appear to have always realised Monks aims; bop orthodoxies intrude and conflict with his more melodic overall concerns. Round about midnight suffers from the front line; Humph has some interesting trumpet from ldrees Sulieman; Thelonious gets the stride treatment. The trio sides at the second date include four Monk pieces: Ruby my dear, Well you needn’t, Introspection, and Off minor. It is interesting to hear Blakey’s swing-period technique change over later tracks and open out into his more flexible but assertive ‘front-line’ style. The July 1948 date has Monk leading a quartet featuring Milt Jackson on vibes, backed by John Simmons on bass and Shadow Wilson on drums. There is a marvellous internal balance and stimulating interplay between piano and vibraharp that produces outstanding jazz. In the wry but remarkable reworking of the traditional blues in Mysterioso, the pianist slips in chords and jagged phrases that heighten and point up Jackson’s fluid solo, and Monk avoids the bop format of identical opener and closer by varying the final recapitulation. There’s magic in the animated I mean you. and the harmonic and rhythmic interweaving in Epistiophy. Three years later, Jackson is back again with Monk on a quintet date, with Sahib Shihab on alto and Blakey on drums. The inclusion of the horn restored the bop combo front line and rhythm, but everyone seems at home with Monk’s material, giving good accounts of Straight, no chaser and Four in one, with an exemplary Criss cross. A final session in May 1952 has Monk leading a sextet including horn men Kenny Dorham, Lucky Thompson and Lou Donaldson, with Max Roach on drums. According to Lion, the singles sold well in Harlem and black areas of a few other big cities, but it took several years before the white jazz audience began to buy. Apparently the legend of Monk as an inept pianist persisted. But these tracks, concise performances for issue as 78s, are today of historical as well of musical interest, since they offer the first recorded versions of many Monk compositions now accepted as an essential part of the jazz repertory. Thereafter I came across Monk in other contexts. Norman Granz included him on piano in a reunion of Bird and Diz in 1950 – moments to treasure! And then two Prestige sessions in 1954, with the Sonny Rollins Quartet and the Miles Davis All Stars. There are some inspired solos in all that music. So when the news came that Monk was to tour Britain in 1961, I knew, to a degree, what to expect. And I wasn’t disappointed.

When Monk started composing in the early 40s, he was totally involved in his music making. Teddy Hill, his boss at Minton’s, has told of the long after-hours sessions at the club piano, when he had to plead with Monk to leave, so that he could lock the place up. He spent hours practicing when at home, unchallenged by the neighbours. Mary Lou Williams remembered his obsessive playing of new compositions, going on night and day until he was stopped. His ideas fired his contemporaries, from Gillespie and Parker, Bud Powell, Tadd Dameron, Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, John Coltrane to Steve Lacey; they have all acknowledged their debt to Monk at various times. Nellie, his wife, said that he never attempted to do anything else but play music. And he was not prepared to compromise just to land a job; he would not play down to audiences. As Steve Lacey commented “. . he’s the only man I ever met who really does exactly what he wants to, with no jive at all”. Monk had his cabaret card withdrawn in 1951 after being involved in an incident with the police, barring him from playing at night clubs in New York. This left him dependent on his earnings from occasional recording sessions, and in those lean years Nellie had to go out to work to help support the family. If ever a man needed a Guardian Angel in the 50s, it was Thelonious Monk. Luckily, one was right at hand, already in New York. In 1951 the wealthy Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter abandoned the boring life of a diplomat’s lady in Mexico City and chose to dig the jazz life of bustling New York. In a very short time she became a wellknown figure on the city jazz scene, befriending many musicians. Monk was one in whom she took a special interest, helping him and his family. She proved instrumental in having Monk’s cabaret card restored in 1957, so that the pianist was able to take a quartet into the Five Spot Cafe. The young John Coltrane left Miles Davis to join Monk on the gig, which caused such a buzz among the New York jazz audience that the group were invited to stay and work all through the summer. That same year, four new albums of Monk's music were released by Riverside Records, and met with wild critical acclaim and the accolade of five-star reviews in Down Beat. Another release, on the Atlantic label, of Monk with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, further boosted his success. In 1958 and 1959 he was voted Top Pianist in the Down Beat Critics Poll, as well as being well received at the Newport Jazz Festival. From then on, Monk prospered...

When Monk started composing in the early 40s, he was totally involved in his music making. Teddy Hill, his boss at Minton's has told of the long after-hours sessions at the club piano, when he had to plead with Monk to leave so he could lock the place up. He spent hours practicing when at home, unchallenged by the neighbours. Mary Lou Williams remembered his obsessive playing of new compositions, going on night and day until he was stopped. His ideas fired his contemporaries, from Gillespie and Parker, Bud Powell, Ted Dameron, Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, John Coltrane to Steve Lacy; they have all acknowledged their debt to Monk at various times. Nellie, his wife, said that he never attempted to do anything else but play music. And he was not prepared to compromise just to land a job; he would not play down to audiences. As Steve Lacy commented: "...he's the only man I ever met who really does exactly what he wants to, with no jive at all". During the long spells of unemployment until the mid-50s, Monk had plenty of time to compose; some fifty pieces came out of this period. When the jazz audience began to catch up and accept him, when performances and touring left him less time for composing, he set himself the objective of establishing this repertory. And with typical single-mindedness, that is exactly what he achieved in the next decade, when performances and touring left him less time for composing. After a decade of international fame, the 70s brought periods of illness and enforced semi-retirement. For many years Monk lived at the home of the Baroness; she remained his watchful patron and confidante until his death in 1982. It will be interesting to see how future generations of jazzmen will treat his body of work. The surprising thing is that it has attracted attention in a wider context. 'Straight' musician Gunther Schuller has written 'Four variants on a theme of Thelonious Monk (Criss Cross)'. And a recent Radio 3 piano recital of American piano music included transcriptions of solos from Monk's Round Midnight and Monk's Point. Monk lives! Written 1989 Revised 1996 |

|