| With the RAF in India #3 | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||

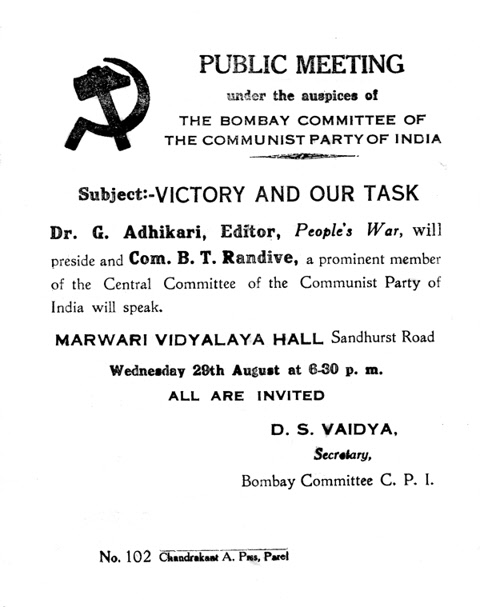

In the general post-VJ Day confusion there is a drop in demand for ground radar mechanics and I am sent to an RAF station at Adgodi, on the outskirts of Bangalore in South India, for retraining to service airborne radar gear. It is pleasant to meet up with several acquaintances among the new intake, but when we report to the orderly room to check on the course, an indifferent admin type tells us there are no vacancies for late arrivals. Nor, he adds, are there enough of us to justify setting up a second course. So we settle in and await developments: Jack is still here, due for a posting, and I'm lucky enough to grab a spare bed in his hut, so we can compare notes on our travels. They find ways of keeping us occupied while our fate is decided. Sent to sort and clear away some long-dismantled aerial mast sections, we need help to manhandle the big wooden frames, and have first to assemble a portable derrick. The components of this have been rashly dumped in the open for several months, so it is not altogether surprising that when we try to lift the wooden spars, they crumble to powder, leaving us clutching the metal bits at the ends, while hordes of termites scurry away over our feet. A closer look at the aerial frames reveals that they are in no better shape. Anxious to please our masters, we collect all the metal fittings, solemnly present them to the technical stores, with a token bag of wood dust and a few inadvertently crushed termites. I bet that buggers up their inventory. We are in no hurry to leave this place. It's the cool season in South India: steady sunshine, day temperature around the eighties, the nights refreshingly cool. I spend my spare time catching up with my sunbathing. The camp is within walking distance of the military cantonment area of Bangalore, centre of No.2 Army Command in India. The place crawls with military police determined to ensure that strict army standards of dress are observed at all times by BORs (British Other Ranks), and that no one wanders into the rest of the city, declared out of bounds to all servicemen. Fortunately the RAF proves more relaxed about these things. There are only a few permanent staff at Adgodi camp; most of the inmates, like me, are just passing through, wanderers between small technical units, unused to the tighter discipline of large camps and installations. In off-duty hours, we are given the privilege of exchanging uniform for civilian dress when we leave camp. Having acquired a mahogany sun tan, I acquire an outrageously multi-coloured shirt to go with it, pose as a civilian and wander out of the cantonment with impunity, despite suspicious glares from officious MPs, to mingle with the general populace. The out-of-bounds situation is largely the result of recent civil unrest. The 'Quit India' movement has a strong following here, yet I find the locals decidedly friendly on these excursions. I visit several cinemas to see Indian films—mainly naive but lively musicals—and the people I sit amongst regard it as a novelty to have a European in the audience. Once convinced of my interest, there's no stopping volunteers explaining plot and dialogue, filling me in with gossip about stars and directors, recommending other films to see. After being regaled by my glowing accounts of these trips, Jack decides to put things on an official basis. He persuades a friendly Indian flight-sergeant, a member of the camp permanent staff, to organise an official goodwill tour of the city. Local patriotism succeeds in getting permission to ignore out-of-bounds restrictions, and rustles up transport too. We drive off one morning, a party of twenty, on a guided tour. Bangalore proves to be a pleasant open garden city with wide tree-lined roads and parks in the central area. We start our tour at the science colleges in and around Cubbon Park, visiting the physics, radiology, spectroscopy and radio laboratories, largely endowed by enlightened ruling princes. It is a sharp contrast when we move to the older part of the city, round the market, where the party spreads out to sample the attractions of the hole-in-the-wall shops in the narrow winding crowded streets. This suits me fine as I want to visit an address in the locality, passed on when in Bombay; it is the local communist party branch, where I'm told I'll find cultural as well as political links.

Jack accompanies me, but we are soon confused by the erratic numbering along the streets, until we realise that the apparent lack of continuity at intersections is because the numbering of buildings runs off the main street, round quiet alleyways and back. When eventually we track down my given address, the premises are shuttered and seem deserted. We knock several times without result, then just as we are about to retreat the door opens a crack, and a dimly-glimpsed figure informs us that we are at the something-or-other manufacturing company, and they are closed. Maybe we are adrift... maybe we should have a password... I recall seeing local newspaper reports of knife attacks on sellers of left-wing papers in the area. But the conversation comes to a dead end as the door is firmly shut in our faces. We decide to call it a day, rejoin the tour in time to hear our enthusiastic guide saying that all that existed of Bangalore in the sixteenth century was a mud-brick fort and a small bull temple built by Kempe Gowda, chieftain and founder of Mysore state. During the eighteenth century when Hyder Ali and his son Tipoo Sultan rose to power in Mysore, the fort was rebuilt in stone, only to be demolished during the wars with the British. We move along to inspect the remains of the old fort: it is not very impressive. A part of the wall has been restored but only, apparently, to accommodate a large notice proclaiming that "Through this breach the British launched their final assault..." We clamber on to the sagging ramparts then descend to peer into the gloom of an evil-smelling dungeon. A plaque over the ornamental doorway informs visitors "Here were confined Captain (afterwards) Sir David Baird and many others prior to their release in March 1785". The chronicles of the British Raj relate that Captain Baird was incarcerated for four years during the wars with Hyder Ali and the French, but returned a few years after his release, having risen to the rank of major-general. After roundly defeating the opposition he promptly demolished the stone fort. Honour satisfied, he departed for Egypt and clobbered the French forces there, called at South Africa where he wrested the Cape of Good hope from the Dutch, and then went to Spain, where his luck ran out. He lost an arm at Corunna, and was retired after receiving the thanks of a grateful Parliament. Our tour moves on to the Bull Temple, in the south of the city. When the ghari pulls up we are met by hosts of cheering kids, streaming from all directions. Someone spots the vintage brownie box camera sported by one of our group and asks him to take photographs of a huge floral decoration that has been made up for a procession. Itinerant photographers process prints on the spot for clients; the kids expect the same service, and are visibly disappointed when snaps are taken but no prints immediately forthcoming. But we reach the temple without incident, a remnant of the crowd still vigorously cheering in blithe ignorance of this lapse on our part. We slip off footwear in the courtyard: inside the temple, it is cool and dark after the brilliant sunlight. As eyes adapt we become aware of the huge black stone seated bull that towers above us, gleaming in the light of a few oil lamps—Nandi, sacred mount of the god Siva, some fifteen feet high and twenty long, impressive, menacing even. The place fills up with children, there are festoons of flowers and paper decorations everywhere in readiness for the festival. We give some coins as an offering and are presented with heavy-scented champak blossom. (I carry mine back to the billet and lay it on top of my mosquito net for the night, doze off drenched by its perfume. Next morning it is gone, swiped by some marauding monkey, but its fragrant presence lingers). We investigate one of the four watchtowers erected by Kempe Gowda to mark the boundaries of his township, now adorned by a multilingual plaque announcing this fact. Then, to round off a crowded day, linger a while at Lal Bagh, gardens laid out by Hyder Ali and Tipoo Sultan in the eighteenth century, landscaped in the Mughal manner with trees, lotus ponds and lakes, and a miraculous abundance of red roses. It is a consoling thought that even while rampaging revengefully round flattening everything in sight, Sir David had, sensibly, decided to spare this haven for posterity. ■ © Harry Turner, 1999. |

|