and the alto sax of Charlie Parker wails torrendously from the newly installed bank of 50 drive-units in the wall-mounted loudspeaker enclosure. Lovely. Charlie’s music has been one of my obsessions since first I heard him on record, way back in the days when the trad-bebop feud was raging amongst jazz fans. Before I heard Bird, jazz was simply happy-go-lucky music-making: the experience of Parker’s music was an ear-opening experience and a mind-blowing revelation...

Contentedly, I flick the volume slide up a notch to drown the dismal thumping of protesting neighbours.

The last unison chorus fades and I realise that the desperate banging on the wall has been supplemented by a sharp rapping on the door. I investigate and find myself apologising to an indignant Jo Withisone, who has guided a wandering fan to the studio and been kept waiting on the doorstep. Introductions reveal that the wf is Joe Patrizio, with a few views to express on my non-article in the last Zimri.

—Harry, he starts the moment we sit down, you’re right in saying that you don’t need words to communicate—but you do need language. Maths, art, music, etc., are all languages.

—I recall that Edward Lucie-Smith once described modern art as an invented artificial language which is native to nobody, I comment, a sort of Esperanto which must be deliberately learned through hard study. I like that emotively off-putting “hard study” bit... Ted obviously intended the remark as a hard criticism of whatever he regards as “modern art”, but surely it’s a comment that applies to all periods and styles of art?

—Yeah, nods Joe, as you said some critics try to impose irrelevant standards on an artist’s work, and end up condemning it. However, this sometimes operates the other way... And what annoys me right up to here, is the clap-trap spewed out to “explain” a painting or a piece of music. If what you say is true—and I believe it is—the artist has used paint, music or whatever, because what he has to say cannot be said in words. Why then, oh why, must some idiot translate the untranslatable?

We drank to that.

—Of course, goes on Joe, as art is a language, I suppose we have got to learn it. But can we learn it? And have the artists any right to be angry with us if we can’t?

—Not so long ago the American painter Jackson Pollock filled up large canvases with chaotic doodles that couldn’t be regarded as paintings in the accepted sense. But in less than a decade they were not only accepted, but part and parcel of the mainstream of painting.

—Well, resumed Joe, personally I feel we learn the language by this sort of absorption—looking and listening—with just a little guidance from one who knows it.

Jo decides it’s time she joined in.

—That’s fine if you’re in an environment conducive to looking and listening, and a guide is handy when needed. Like the way we learn our own language, of course: it starts so early that later on we aren’t aware of the effort that was involved, or even of the way our thinking is coloured by the in-built cultural conditioning that is part of the process. One learns the rules in a way that often leaves you unaware of the rules —somehow it’s all regarded as a ‘natural’ process. Until you start to learn another language and then the rules become obvious because they have to be consciously learned. Which is why it’s best to live in a country while learning the language, rely on cultural immersion, absorption plus guidance, to achieve any sort of fluency.

—It’s odd, I add to Jo’s point, how people realise this so far as the spoken or written word is concerned. There’s an awareness of the problems of illiteracy and an urge to tackle it. But there seems less awareness of the problem of ‘visual illiteracy’, and that is what I feel so concerned about.

—Let’s get back to the critics explaining art to us, persists Joe. I can’t accept that it can be explained because for me art by-passes the verbalizing critical faculties, and goes straight into the soul—for want of a better word. I can’t explain why a piece of music or a painting moves me—but there is an excuse for me: I don’t know the language. But I’m pretty sure that even Harry couldn’t say why a particular piece of artwork gets through to him. You may be able to explain the cleverness or originality of it, but not why it twangs your insides...

I grunt agreement.

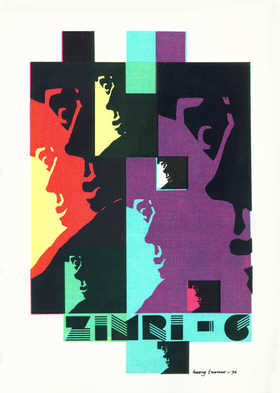

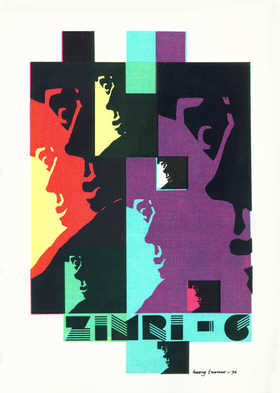

—That’s exactly why I talked around an article in the last issue but never actually got around to doing it. And probably why Terry says about the last cover design: “I don’t know what it is, but I like it”. A comment I find at once gratifying and mystifying: was the image so obscure?

—What did start you off on it, asks Jo.

—Hard to say that in retrospect. I was intrigued by this anxious face peering backwards, with its Kafkaesque implications. It became a motif in an exercise prompted by comments made about colour printing at the Tynecon, and an urge to try the results of overprinting three transparent dyes in screen printing. Initially it was a visual thing—I mentally manipulated the Kafka image in terms of a basic grid of squares, with permutations of side and colour, and then it was a matter of translating it into practical terms of screen printing.

|  |

It was all sorted out at a non-verbal level, and it’s impossible after the event to sift out the intuitive links that related the strands of the problem—under pressure of an editorial deadline I might add. If it has to have a title by way of explanation for some folk, I guess I’d call it Portrait of K, because to me it conveys something of the unease of the fugitive that is the essence of Kafka’s Trial and Castle...

—But that’s not the end of it, interrupts Jo. Lisa tells me that when mailing the last Zimri, she kept seeing the cover from different angles, and realised that the whole character changed with the viewpoint...

Turn it round so that the base of the image becomes the righthand side, and there’s another eye staring at you.

—Wow, breathes Joe intrigued, The Accusers of K. Right?

—What’s in a title, I grin.

Cover of Zimri #6, (1974), screen printed in black, yellow, red & cyan

(The remarks attributed to Joe Patrizio are lifted from his letter of comment: Jo Withisone’s comments reported verbatim)

from Zimri 7, January 1975 |