| Early Memories #7 | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||

I'm told that jobs were scarce in Manchester during 1936. That was when my father joined the unemployed. Mother took in a lodger to help pay the bills, and I was expected to go out and earn my keep after completing a formal education at the local central school in the summer of that year. I promptly worked myself into and out of three jobs in almost as many weeks. Months before I'd seen a nearby design and exhibition company advertising for apprentices to train in their display studios. I set my heart on getting in there – no routine office jobs for me, I decided. But by the time I was free to apply there mere no vacancies. To rub salt into the wound, well-meaning relatives at a family conference on my future showed deep disapproval of such a dodgy career; he needs a job in commerce, with solid prospects, they opined. So I was despatched, reluctantly, with an introduction to a firm in a dingy office block in the back streets of the city centre.

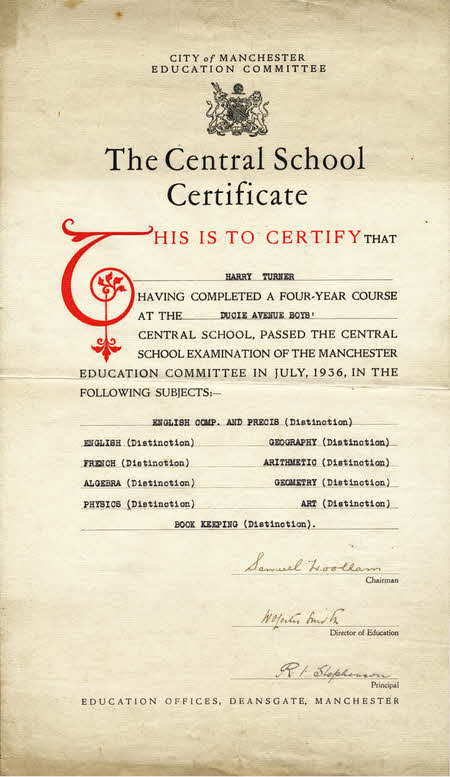

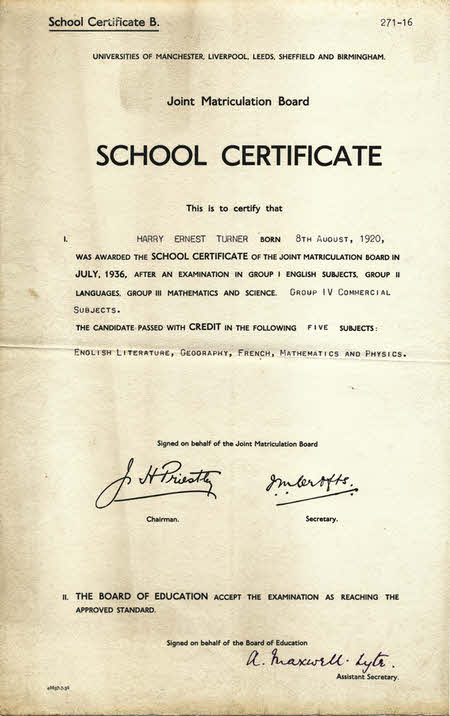

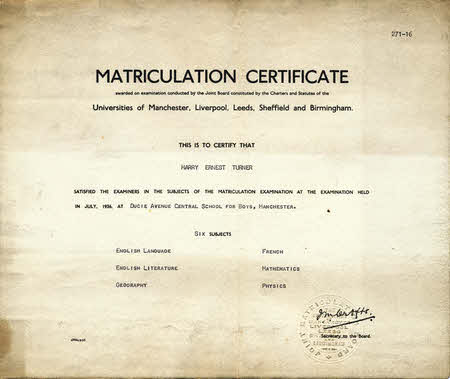

There was no difficulty in getting hired after I produced my gaudy Central School Certificate, printed in two colours, declaring that I had acquired distinctions in all ten subjects listed. I was to find it faintly embarrassing that this document proved such a sure-fire job lander, while the drabber School Cert and Matriculation certificates, representing somewhat higher standards of attainment, received scarcely a glance.

I spent the whole of one day at that first job, running errands, at everyone's beck and call, and departed that same afternoon after announcing they needn't expect me back. I was sent promptly to another city office. Again there was no real job or prospect of training, and youthful arrogance had me marching out after only a few days. I tried a third place. It was no different, though this time I heeded my dad's advice and stuck it out to the end of the week, and drew a few shillings wages before declaring that I wasn't staying. Shocked relatives washed their hands of me, my parents no doubt despaired. I was left to seek my own salvation. If I couldn't break into the art world, I decided, then science offered more interesting prospects than boring commerce. I landed an interview with a chemical company in the industrial wastelands of Clayton [Anchor Chemical Co. Ltd.] and this time I was quite happy to let the CSE certificate exert its charm on the director sounding me out: it clinched the job.

That was when I met Harry Nelson, another young hopeful hired at the same time - I never checked if he too had brandished a fancy certificate - and we soon became firm friends. He intrigued me, his background was so different from mine. He lived in Oldham, a place occupied by a large clan of Nelsons. In his spare time he was a musician, an accomplished trombone player who spent a goodly number of his free hours playing at dances with a local band. His brother was star player in the group, his dad and uncle handled bookings and transport, while his girl friend stood in as vocalist. He left me with the distinct impression that the Nelsons had the Oldham and district dance band scene all tied up. He travelled to work at the chemical plant on a motor bike, swathed in a vast leather coat, fastened tightly over several undercoats on chilly days, with rubber waders anchored to brace buttons, large gauntlets, a leather helmet and rubber goggles. The routine of casting off all this gear on arrival kept us amused while we were busy shaving and grooming ourselves in the cloakroom, ensuring that we reported for duty meeting the high standards of appearance demanded from junior staff. Collars and ties and sober suits were the norm; pullovers and jerseys were frowned on. One morning, Harry rushed in at the last minute, looking the worse for wear, confided that he'd had a hectic band engagement the previous evening, got to bed in the small hours, overslept, and had to dash to work without breakfast. We cherished a theory that Harry hung up all his travelling clobber overnight, so that he could just step into it each morning and button and zip it all up automatically. It seemed so that morning, because as he fought his way out of his protective cocoon and unwound a long woolly scarf from his neck, Eric gave a guffaw: "Hey, you've forgotten your collar and tie!" Amid laughter, Harry clutched despairingly at his throat and sneaked a look in the mirror. In pre-war days, to prolong the working life of shirts, detachable collars were provided, held in place by back and front studs, so that a freshly laundered collar could be donned and suggest a clean shirt too. Having confirmed his state of undress, Harry promptly redonned his cycling gear and rushed out. We heard the sound of his bike starting up and off he zoomed. "He's surely not going all the way home, is he?" asked Frank, incredulously, "there'll be a stink when he turns up late". "There'd have been a stink if he rolled in minus collar and tie," we chorussed. Sure enough when Harry returned, correctly attired, he was chewed up for arriving late without good reason, and had his pay docked that week. The bosses had the workers where they wanted them in those days. Mind you, he'd already been in trouble for skipping an evening class at the technical school we attended, when there was a small matter of a conflicting dance date that got priority. The firm encouraged us all to study for an Institute of the Rubber Industry qualification, and paid for the classes. Rush-hour traffic and bus queues meant that there wasn't time for any of us to return home for tea after work on these tech nights. We brought sandwiches and stayed on since the tech was only a few minutes walk away from the works. Eric brought in a portable record player and we listened to each other's records while brewing up and chatting over our grub. The nightwatchman left us to it, arranging his rounds so that he came and locked up after we'd departed. One evening we were disturbed by a director who'd stayed late, and heard our recital as he passed down the corridor. Obviously he didn't think much of our choice of music since he told us that he'd bring in some real music for us to listen to, and he did. Fat imitation-leather-bound, goldblocked volumes of D'Oyly Carte performances of Gilbert and Sullivan operas - complete operas spread over umpteen 78 discs. Hypocrites that we were, we buttered him up and thanked him profusely, then the minute his back was turned shelved all our disagreements on the relative merits of popular music and the classics, to unite in expressing our loathing and contempt for Gilbert and bloody Sullivan. So only token sides ever got played, whenever the director was working late, or when his secretary flitted by within listening distance: we knew she'd report back if his records weren't on the turntable. We were nagged by the risk of damage to this priceless collection while in our possession, and it was a relief to return it at the end of term. My general musical education had been innocently acquired from listening during the thirties to the records played by my several young aunts and their boy-friends in gran's house, and the light entertainment on the wireless. I became familiar with most of the dance bands of the day... Carroll Gibbons and the Savoy Orpheans, Harry Roy, Jack Hylton, Bert Ambrose, Roy Fox, Nat Gonella and his Georgians, Henry Hall ("This is Henry Hall speaking" he used to assert as if there were some doubt). Most of them had a band within the band, a small group of musicians playing in a freer context. The plummy tones of Carroll Gibbons would announce a number to be performed by his 'Playmates', the ebullient Harry Roy would join his Ragamuffins in novelty numbers like 'Dinner Music for a Pack of Hungry Cannibals' or ‘Where did Robinson Crusoe go with Friday on Saturday Night?'. But the title didn't matter, somehow the music seemed more lively and interesting away from the constraints of the full band and their stock arrangements. On our brief evening sessions at the chemical works I found myself listening more and more to the treasures from Harry's record collection. He was totally in love with the sound of the trombone. I sometimes wondered if he heard anything else on the records he played. He brought American recordings featuring Kid Ory, Miff Mole with Red Nichols groups, Jack Teagarden, and sumptuous renditions of sentimental ballads by Tommy Dorsey which sent him into ecstasies. My ears were opened by his enthusiasms: I can cheerfully date my interest in jazz as starting from this period. Discovering jazz was not a blinding revelation, hearing some hot lick that held me enthralled for evermore, but a stumbling appreciation that lurking in the ephemeralities of the popular music of the day was something of permanent worth. Meanwhile my parents were relieved that I'd settled down in a job and contributing to the house-keeping, after my pyrotechnical start in the labour market. The relatives disdainfully kept their distance. I kept on drawing in my spare time and even started to sell small illustrations to Tales of Wonder, the first British sf mag to appear on the scene. When a rival magazine, Fantasy, appeared and showed interest in my artwork, I saw a career as a freelance illustrator opening up before me, and dreamed of escaping from the chemical works... The outbreak of war upset all plans by providing unlooked-for opportunities of a new career in the armed forces for us all. Frank opted for the navy, the rest of our elite group preferred the RAF. Harry was called up before me: I enjoyed a brief reprieve when local records were destroyed in the 1940 Christmas blitz on Manchester. I had been accepted as an instrument maker, but by the time I reached Padgate they decided my eyesight was not up to that meticulous trade and and I found myself reclassified as a wireless mechanic/operator and put on a course. The course took longer than I anticipated as I went on to become a radar mechanic, and I lost touch with Harry. I often wondered how he was making out. When next I heard from Harry I was on an RAF radio course at Birmingham tech. He was at a repair section near Henlow, and had just been appointed 'duty trumpeter', being expected to make warning calls on his trumpet in the event of impending air raids or other emergencies. He was allowed time off to practice every afternoon in the bandroom. I bet he put heart and soul into those rehearsals in between taking extended breaks in a nearby cafe. It was really no surprise when he wrote a few months later to say, smugly, that he was having the time of his life playing trombone in a touring RAF dance band. I was convinced that his dad and uncle would be looking after the engagements and transport, with his girl friend providing the vocals of course. ■ © Harry Turner, 1999. |

|