| FOOTNOTES TO FANDOM #15 | FOOTNOTES Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||||

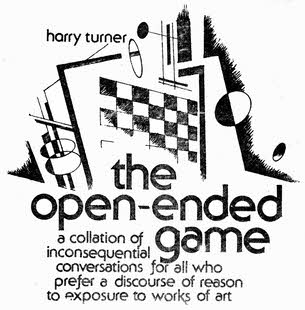

PRELUDE 1 – Spring We are hungry after a busy evening discussing plans for zimri. I return from Nick's Grecian Grill with chicken and chips and Lisa pops the food, still wrapped, into the oven to keep warm while we clear the papers off the table. – Hey, whatever happened to that article on art you promised? she asks out of the blue. I blush. Long ago, when Zimri #4½ had just been mailed, I thought it a good idea to write an article about art, based on all the comments. Gaily I jotted down points for inclusion as they occurred to me, but as the list grew longer my enthusiasm waned. I never get around to finishing the job since there are always other things to do of more pressing urgency. Secretly, I hope Lisa will forget the whole thing. No such luck. – Well... I had a few doubts about it, I confess. My basic problem is that I'm not a writer, just a drop-out from the literate society, hating gratuitous verbalising and lacking the essential faith that everything can be explained in words... Lisa raises her eyebrows: they disappear behind her fringe. – But you can't think except in words, she asserts, and you can't express your thoughts until you put them into words. I try raising my eyebrows toward a receding hairline but don't make it. – You may argue me into a corner occasionally, and make me admit that some things can only be expressed in words, but if there's any communication in art it's in terms of sharing ideas, feelings, and emotions in areas where words are inadequate... areas where the visual artist often works alongside the musician and mathematician. I warm to the theme. – There are so many possibilitities to be explored. Representation, describing appearances, is only one of them, and today it's perhaps the least challenging. Certainly in this century many Western artists have largely lost interest in the conventions of pictures that tell a story or record a scene, and discarded forms that imitate the visible world in favour of a non-objective world. By invoking narrow, often irrelevant, standards and trying to impose them on an artist's work, critics only confuse the situation. Like, there's no point in demanding realism from the abstract, or literature from everything. There are many guiding standards and no one of them is necessarily right or best. So far as the artist is concerned it's an open-ended situation–by all means try to figure out what the artist is aiming to achieve but, if you haven't a clue, then you can't decide if he's succeeded or even if the result was worth the effort. Art's there to be enjoyed not merely 'explained'. If you want to get inside a picture, then open your mind to the possibilities that the artist has explored and reported on. Be receptive, don't automatically reject the unfamiliar; let it grow on you, live with it for a while. Don't give in to the impulse to make instant judgments and evaluations that obscure what you see in front of you... – Keep going, you're doing fine, encourages Lisa, taking notes. But let's get back to this idea of artists deserting appearances for abstraction. – Well, it seems a general assumption in our literate society that there's a 'natural' way of seeing, that no training is required to 'see' a photograph which reproduces appearances. For a start, nearly everyone who's clicked a camera will agree that it is quite capable of recording things never even noticed in the viewfinder, often producing a print that is a travesty of the mental image the photographer wished to preserve. We have to learn to manipulate a camera to make the images it records approach the images we see. The camera lens is undiscriminating; the eye, guided by the brain, is selective. To the eye, all things appear in focus simultaneously–yet this is known to be an illusion created by the eye's ability to focus automatically and virtually instantly as it scans a scene in depth. We focus on something within our field of vision at each instant, but never on everything. To see at all, we've got to isolate and select in this way. Retinal images are ambiguous, so we rely on all sorts of clues to resolve the ambiguities. In certain circumstances we can't tell whether an object is small and near, or large and distant; whether an unevenly shaded area is hollow or protruding. We help out our imperfect vision with other sense impressions: sound, smell, taste, touch. The brain coordinates these impressions, combines them into subjective images and concepts, to be screened, edited and shaped, to a surprising degree, by our expectations, preferences and prejudices, our immediate wants and needs. With such a complex process it's not surprising to find that cultural conditioning plays a part in determining what we see, and that non-literate cultures exist that have developed different ways of seeing to us. Thus Marshall McLuhan tells of the difficulties experienced when showing 'training' films in African villages. The adult audiences missed the intended point of many films because of the taken-for-granted conventions of literate culture that had gone into their making. The Africans tended to concentrate on irrelevant background incidents at the expense of the main 'story-line'; they needed perceptual training before they mastered the in-built visual conventions of the film to get the message. In a similar way, many forms of non-objective art demand changes in the way people see: many people seem unable to separate the superficial decorative appeal of an abstract composition from its constructive significance. They are the visual equivalent of folk who–as Tom Lehrer puts it–like a tune they can hum... they appreciate the melodic element in music but can't grasp its polyphonic depth... I break off, my nose twitching. There's an acrid smell of scorching paper. During my monologue the oven has approached the crucial temperature of 451ºf. With a yelp Lisa dashes to investigate, and returns plucking charred newsprint from our supper: in the panic, fortunately, the article is forgotten. Smoked chicken has a distinctive flavour. Given time, I think I could even acquire a taste for it. PRELUDE 2 – Summer I turn into Manley Road feeling at peace with the world. A voice yells my name, shattering my reverie. On the opposite side of the road Peter Presford is climbing into his van. – Lisa's out, he informs me, can I give you a lift back into town? The sun blazes down, the pavement is hot; I feel in no hurry to dash back to the dusty city centre. We chat briefly and then I wander on to the coolness of nearby Alexandra Park to pass the time until Lisa's return. It's pleasant near the lake. I whip off my shirt and stretch out on the grass to sunbathe and read Solaris. I'm eager to find how the novel (or at least its translation) compares with the film, which I'd recently seen in London. Vadim Yusov's photography made Tarkovsky's film an unforgettable experience for me, right from the opening sequence. Those Monet-like views of water, leaves and waving reeds, the woodlands and vibrant patterns of sunlight; Kris awaking to see Hari, her head a glowing silhouette against the bright Solarian sky–all golden russets, ochres, yellows and warm browns on white; one sudden zoom-in on the bulkheads of the station that momentarily converted the screen into a vast abstract, two great green expanses toning sharply to define a common edge, a keen vertical stroke hovering on the Golden Mean... I lose myself halfway through the book before recalling the purpose of my trip. Back at Manley Road I find Lisa cooling off in the garden, hiding behind huge sun goggles and a diminutive bikini. – How's the article going? she promptly demands. – In his Philosophy of Art Herbert Read recommends that the best preparation for a true appreciation of contemporary art is a study of the writings of Whitehead and Schrödinger. I just wondered if by any chance you have any of their volumes in your library, I improvise wildly... And then falter into silence before the inscrutable gaze of those damned black goggles. Inwardly I vow to settle down and sort out all those scribbled notes the moment I get back to the studio. PRELUDE 3 – Autumn Nick delicately skewers chunks of lamb as he prepares the kebabs. – Eet ees all a matter of dunamei summetros, eh? he quips. Nick is the only eating-house proprietor I know who is an authority on dynamic symmetry. Over the months, it has become the staple topic of our conversation, the way most folk exchange pleasantries about the weather. So far as I recall, it started when Bronowski's Ascent of Man series was being screened on TV and he'd been wandering around the magical isle of Samos, discoursing on Pythagoras' discovery of the mathematical basis of musical harmony and the fact that the right angle is something you turn four times to point the same way. Nick was all steamed up by this episode. In between tossing and turning burgers on the charcoal grill, spitting chickens, spreading relish on hot dogs, and stuffing vine leaves, he revealed that he too was born on Samos, and a devoted admirer of his compatriot Pythagorus, first genius and founder of Greek mathematics. It seemed I was the only immediate member of his clientele who shared this deep interest. Our friendship grew and blossomed. I find that Nick really is an expert. We talk about early cultures whose arts and architecture are based on static symmetry, and the big breakthrough when the Greeks came to realise that there is a symmetry of growth and arrangement of plants, shells and the human skeleton. We join in deprecating the influence of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, unsuccessful Roman architect, purveyor of false theories on the Greek tradition, and inspirer of pseudo-classical architecture. We discuss the golden section and whirling square rectangles. When lingual difficulties intrude, we scribble diagrams all over the counter menu–much to the disgust of Nick's wife who has to search out another copy for impatient customers. Tonight I am telling Nick about Jay Hambridge, self-styled American expert on dynamic symmetry and author of innumerable books on the subject published by Yale University. On a visit to the British Museum he found the marks of a compass on some unfinished Greek volutes, and realising their significance he was able to reconstruct the long-lost method of drawing an Ionic volute. Nick's luxuriant moustaches curl in a faint sneer. I sense the gesture implies that Nick would have passed that information on to Jay without all the research and hard work. I hastily point out that Hambridge's discovery was made over sixty years ago. Nick promptly forgives him and starts off on one of his anecdotes while the kebabs sizzle. It's a story from Didorus Siculus, a Sicilian Greek historian, about the sculptor Rhoecus, who served his apprenticeship swiping ideas from the ancient Egyptians and passed on his sculpting skills to his sons. Chips off the old block, these two. Telecles in Samos, and Theodorus in Ephesus, each carved half of a statue, and lo! when the two parts were brought together, they fitted so exactly that the statue appeared to be the work of one man. When I regale Lisa with the story later, she is impressed. – Maybe I should get Nick to write this ruddy article on art, she muses. INTERLUDE – Winter I like to keep up with what the younger generation of artists is doing. The Manchester Whitworth Gallery puts on a regular exhibition of work from colleges throughout Britain–the Young Contemporaries–and it's usually well worth a visit. There's a decided element of the surreal abroad this year, not only in the works but in the titles. I tend to regard titles on works of art as superfluous except as a convenient means of identification, and the large proportion of works titled 'Untitled' shows that I am not alone in this prejudice. But I admire an apt title: 'I don't know, but it took a long time' seems to anticipate the obvious question. There are a few exhibits here that provide an opportunity for audience participation, like opening boxes and switching on mechanisms. There's one item combining both activities near the gallery entrance. A young lady has opened the box but neglected to switch on the power, and is bent double peering into semi-gloom. Always ready to oblige, I lean over and close the switch. A red neon sign promply flickers into life inside the box. ECHO it proclaims, and immediately a progression of ECHOs becomes visible, receding to infinity. – That's good, announces Lisa (for it is indeed she) staggering back in amazement. Thank ghod you rescued me–I was beginning to get vertigo staring at a million images of me disappearing into the depths. How's it done? I switch off and on again by way of demonstration. – Two-way mirror at the front and another mirror behind the neon sign, I guess. When the sign lights up, the reflections keep battering between the mirrors. We compare notes. Lisa hasn't been round all the rooms, and as it's my second visit I offer to give her a conducted tour then promptly get entangled in a maze of chicken wire hanging from the ceiling. It has a myriad tufts of green wool fastened all over it ('Just a little green' says the catalogue). When I realise it's an exhibit and not a man-trap, I stop thrashing about and extricate myself. Meanwhile there's a strangled squawk from Lisa, who's nearly tripped over a faintly obscene piece of soft sculpture on the floor ('Afterbirth'). An attendant hovers in a doorway, eyeing us suspiciously, but we are chuckling over other sculptures–a laced boot whose toe-cap is metamorphosed into the corked neck of a bottle (titled 'Bootle', what else?), and a clenched fist inside a cracked glass jar ('Bottled Violence'). Like I say, the surrealists are out in force this year. As we wander round the conversation turns to inspiration and creativity. – It's a funny thing, but the present upsurge of interest in the creative process is largely due to the reaction to Sputnik in 1957. The US hawks panicked with the thought that their educational system might not be producing enough original scientists to maintain the American technological lead in the world. Before the war, creativity seemed to be regarded as an offshoot of genius, granted by nature and, like the weather, something we can do little about. But in the presence of the Soviet "threat", creativity could no longer be left to chance. Funds were made available to many workers in the field once government and military viewed research into creativity as their legitimate concern. So creativity isn't regarded with quite the same awe it once had. Now it's akin to problem-solving: an ability to play freely with concepts, ideas, and relationships, of recognising new and significant patterns and combinations. Fundamentally, there's little difference in the creative process, whether it's painting a picture, writing a poem, or formulating a scientific theory. A mathematician is often an abstract artist who hasn't cultivated the ability to express himself in a plastic material... We wander into the last gallery, admiring a large black-and-white 'Car Pet' spread before us. – Creation is a solitary experience. As an artist, I arrange or discover a problem and set out to solve it, and when I have the solution the basis of evaluation as to its 'rightness' is inside my mind. I know whether it's successful or not, whatever anyone else may say. – That sounds a bit arrogant, Lisa chips in, and although I agree with you in part, aren't you forgetting something called 'communication'? – No, the artist's sole concern is the act of creation, and at that time he's not concerned with other people's reactions. We then become aware of a pleasant pulsation, an unobtrusive sound modulation that has gradually asserted itself at a conscious level, intruding on our conversation. It emanates from what at first glance appears to be a work bench, with a beam across the top carrying a taut string, partly concealing an impressive assembly of electronic gear. We pause, entranced by the subtly manipulated vibrations. – Lovely, enthuses Lisa, what's it called? I consult the catalogue and read: – 'Words fail me, that's why I made it'. POSTLUDE – Spring, again – So it just won't all fit in, mourns Lisa, glumly surveying the pile of material accumulated in the editorial in-tray. She sifts through it for the umpteenth time, ticking off the essential items on the list and the result comes out a 96-page zimri. – I'll just have to be ruthless, she decides. Thinking of all the production problems and subsequent postal bill, I have to agree. – And so far as your art article is concerned, there's no way I can see you managing to fit in those colour pages you've planned... Then there's the poetry booklet, and if I'm going to get zimri out in time for the con, well, this lot will have to be edited ruthlessly... Her violent gesture dislodges the pile of typescripts and confusion reigns as leaves flutter floorwards. – I get your point, I concede as order is restored, but given more time... – Christ, mutters Lisa fervently, eyes upturned to heaven. – Given more time, I persist, the article would turn out to be a work of art in itself... – STOP! says Lisa firmly. this is what I'll do. I'll print the bits and pieces you've written about writing the article, just to whet the readers' appetites, and promise them that you might, just might, get around to the actual article next issue. How does that grab you? – You're the Editrix, is all I can say. Now, what about the rest of this stuff... ■ FOOTNOTES TO FANDOM #15... |

|